Senora in Xbalba: Ginsberg’s Jungle Queen

A look at the life of Karena Shields, an explorer and early aviator who was friends with Allen Ginsberg.

Years ago, when writing World Citizen: Allen Ginsberg as Traveller, I researched the poet’s 1954 stay in Mexico, where he temporarily lived on a property owned by a woman called Karena Shields. Drawing upon Ginsberg’s letters, journals, poems, and biographies, I found little information about this woman, and Google wasn’t much help, either. Although I believed that his stay with her was massively important in terms of his poetic development, it seemed that it was the jungle solitude that was beneficial for him and Shields did not seem to have been a huge part of his life. As such, I mostly focused on his activities whilst he stayed with her and neglected to dive deeper into her own story.

This was a mistake and I could feel it at the time. There was something missing, something that bugged me… Let’s face it, Ginsberg did not have all that much time for women. They caught his attention if they possessed an unusual level of genius, creativity, or madness, but for the most part he preferred the company of men. Yet although he did not write much about Shields, the little bits and pieces he did write showed her to be quite an intriguing character and one who had earned his respect. Even though he usually failed to name her, his letters depicted a fascinating woman whose life was lived in utter defiance of convention. She sounded more like a character from an old adventure story than a real human—a cross between Colonel Kurtz and Indiana Jones. But again, there wasn’t much to go on and Ginsberg’s letters at this point did have a tendency towards hyperbole. The romance of the jungle got his creative juices flowing.

Over the years, her name kept popping up during subsequent research projects. I saw her mentioned in letters and journals and I realised that he’d seen her multiple times back in the States and had pushed Kerouac to visit her when he was in Mexico. At some point it dawned on me that it was rather strange such an apparently minor figure in Ginsberg’s life had been mentioned in the biographies written by Bill Morgan, Barry Miles, Michael Schumacher, Thomas Merrill, Neil Heims, and Steve Finbow, as well as books like Jonah Raskin’s American Scream. Considering she was a woman with whom he stayed for a few months and wrote relatively little about, it’s quite surprising that she’s so frequently mentioned.

Whilst she did make it into each of these books—and a number of others about the Beat Generation—she appeared only in a brief walk-on role, sometimes with her name incorrect and usually with the facts of her life wrong. Her quirks and accomplishments were mentioned but the writers all seemed a little unsure of these details and there were obvious inconsistencies. Moreover, there was something unreal about her. She appeared in Ginsberg’s life like a guardian angel and then disappeared soon after (arguably the fate of many women connected to the Beat Generation). Unlike other women who impressed Ginsberg, though, Shields did not populate his later dreams (at least not the ones he wrote down) and she did not make appearances in his later poems.

What little information there was, however, hinted at a bigger story and at some point I made a note for myself: “Learn about Karena Shields.” I put it off because it seemed like a tough task with little reward, but whenever I spent a little time digging, I found that there was much more to know. In fact, the improbable depictions of her in Ginsberg’s letters that I’d taken for fantasy had massively downplayed her achievements and missed most of the incredible parts of her life. Where I assumed he’d fabricated parts of her character to impress his friends back home (Ginsberg was trying to be a manly jungle explorer at the time and did that quite a bit), it turned out the opposite was true and he had not come close to capturing the amazing details of her life.

What I found was a woman whose life story read like the script for a far-fetched adventure movie. After much research, I was left scratching my head and asking how she fit all this into her life. To give the barest highlights—as a shameless hook to keep you reading—I will say that Karena Shields earned at least four degrees, including a medical doctorate; was an actress, director, and playwright; was an aviator and explorer; made important scientific discoveries in a wide range of disciplines, including archaeology, anthropology, and medical science, specifically in the fields of tropical disease and Mayan history; owned a large chocolate plantation in the jungles of Mexico; provided free medical care for indigenous peoples whilst also attempting to spread awareness of the richness of their culture; was a successful writer of novels, children’s books, magazine articles, and scholarly monographs; had the same publisher as Jack Kerouac; was represented by Allen Ginsberg as literary agent; and was a respected educator, travelling widely to lecture on her various areas of expertise.

Considering all that, it is incredible that she lacks even a Wikipedia page. A Google search yields next to no information except what can be found in books about Allen Ginsberg. To find anything of real value, one has to dive into archives of old newspapers and magazines and dig up long-out-of-print books. Those newspaper archives are the best results because Shields was, for a large part of her life, the subject of widespread admiration in the American press. Depressingly, however, whilst these reports uniformly acknowledged her stunning accomplishments, they are a hard slog due to their unabashed sexism (she had such a pretty smile!) and racism (what a brave white girl to live among those savages!). Those articles, too, tended towards the fantastic and seem based on dubious facts, so picking apart the real and imagined here was no easy task.

Still, the more I read about Shields, the more impressed I became, and I was determined to put together something substantial about her life and how it intersected with the poetic journey of Allen Ginsberg. In the next section, I’m going to more thoroughly talk about Ginsberg and Shields before later putting together a biography of this amazing woman. Its inclusion in Beatdom, a Beat Generation-centred publication, does not mean that she was a Beat writer by any means or to play up her connections to the Beats beyond what has already been said, but something compels me simply to tell her story because it seems so unjust that no one else has.

Karena Shields and Allen Ginsberg

Let’s start in the middle of the story. This is not only a seemingly illogical and unintuitive place to begin, but it risks accusations of sexism because we’re going to first look at Karena Shields through the eyes of a famous man. Even so, I believe it’s a reasonable place to start in part because Beatdom is a Beat Generation publication, but also because I want to show how he presented her and what was wrong with his account. This is important because there is so little information about Shields readily available and almost all of it comes via Allen Ginsberg. A quick search of Google more or less brings up his claims and people’s interpretations of them, and these are not wholly accurate.

Karena Shields entered Allen Ginsberg’s life in early 1954. Late the previous year he took off on a long journey from New York to San Francisco along an unusual route via Florida, Cuba, and Southern Mexico. It was a tremendously important time for him because it was his first long solo journey and first extended stay outside of the United States, and because it was during his time in the jungles of Chiapas that he started making big developments in his poetic voice. (See World Citizen for more on that.)

In Mexico, Ginsberg attempted to see as much of the country as possible and he travelled cheaply from one town to the next, paying particular attention to the various sites of archaeological importance. Here, he would pretend to be an archaeological student in order to stay for free and be allowed access to the ruined cities he visited. In these places, he took codeine and wrote poems atop the old ruins.

In January, Ginsberg visited Palenque and met Karena Shields, whom he took for an archaeologist. In her late forties, she appeared to him a kindly old lady and given that she owned a large plantation, he possibly assumed she was wealthy. This was an illusion soon dispelled but her poverty was less severe than Ginsberg’s and she would lend him money several times. Ginsberg was flat broke at the time and was learning how to scrape by with the help of kind strangers, and in Shields he found one. She invited him to her finca (farm/plantation) in the nearby jungle. Ginsberg had been moving around quickly, becoming exhausted and disillusioned, and he recognised the poetic potential in staying put for a while, particularly in a jungle environment.

Ginsberg wrote about Shields only a few times. He mentioned her in a journal fragment written at Palenque:

Karive tribes wandering from Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan still b ore ancient Mayan intelligence, and to this day carry the secret of translation of hieroglyphs & theory, according to Karena Shields, who encountered them as a child. Karives know astronomical system, keep theology intact, and can make variant creative forms of old pottery types.[i]

However, he only went into detail in a letter to Jack Kerouac that he began at Palenque on January 18, then continued a week later. It seems as though he was starting to hate Mexico when he ran into Shields at the archaeological site and by the time he continued his letter on January 25, he was much more enthusiastic. After what he admitted was a “bum kick of incomprehensible story,” he wrote an 800-word paragraph that begins:

I was walking around Palenque and ran into a woman who grew up around here—the edge of the most inaccessible jungle area of South Mexico—who had returned six years ago after various careers in the States, a professional archeologist whose family had owned the Palenque site so that she knew it inside out.[ii]

I can’t quote it all because it goes well beyond fair use but it can be found in Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters. In this letter, he describes her and his adventures with her but never gives her a name. She is simply “the Senora” who owns a “cocoa finca.” His depiction of her is heroic and romantic and she is portrayed as extremely knowledgeable. Although he was wrong about her being “a professional archeologist,” he is right when he praises her knowledge of the jungle, the local culture, and Mayan history, even if he moved into the realm of hyperbole. He described her to Kerouac:

the woman knowing from childhood all parts everywhere, and more, being a sort of mystic and medium type personality, as well as learned in the subject—perhaps the person in the world most emotionally and knowledgably tied to these ruins and this area—so that I found after a few days talking, she had been on foot and plane all thru jungles down to Guatemala and in lost cities all places, some even she discovered, had written books (her editor is Giroux) and learned papers and worked for Mexican government reconstructing Palenque and others, owned a few cities in her great tract of land here (hundreds of sq. mi) and, most important, was the only person in the world who knew of a lost tribe of Mayans living in Guatemala on a river who still possibly could interpret codices and were specially on a mission to keep alive Mayan flame—and she told me all sorts of secrets, beginning with outline of Mayan metaphysics and mystical lore and history and symbolism […] This lost tribe apparently had brought her up as child, being in area where her father owned $3,000,000 dollar ranch here and having selected her for confidence. Well all this is sort of corny and amusing but the curious thing is that much of it is true in its most classically corny aspects.[iii]

That last line about the story being “corny [but] much of it is true” suggests that in spite of his telling it as the truth, he does not wholly believe Shields, and one can respect that, for what he repeats here certainly borders on the fantastic. But what is perhaps most fantastic of all—and which defies all common sense—is his claim that Shields was “the person in the world most emotionally and knowledgably tied to these ruins and this area.” How strange that he completely overlooks the native people. After all, he lived with them and was eager to know more about them.

Ginsberg goes on:

It is a great kick to enjoy her hospitality in the jungle—she being starved for ignu conversation tho she is not an ignu herself—[…] We live in an open sided room with continual fire for coffee and food at one end tended by an Indian, hammocks strung up across the room, a great unexplored mountain right ahead looking very near—a few hundred feet thru the brush behind the house are six native huts with families—who work on the plantation, a sort of feudal system of which she is queen and we are royal guests.[iv]

It is important to note the phrase “she is not an ignu herself.” This term is hard to define precisely. Ginsberg seemed at times to use it in reference to someone knowledgeable in hip matters but at other times it referred to someone who was part of his social circle. Certainly, it is a positive quality suggesting a combination of madness and genius. Though Shields was very impressive, she was in Ginsberg’s eyes an old Christian lady and thus not hip enough for the label “ignu.”

A month later, Ginsberg wrote Kerouac another letter. Again, he failed to provide his “Senora” a name but added some more complimentary description:

La Senora, in case I forgot to say last time, is a Giroux-Harcourt authoress, once wrote a best seller about jungle (Three in the Jungle). Ugh. Writing another about mystical Mayans, interesting facts for Bill but she’s a strange case, some good and some nutty and some tiresome about her; her best feature aside from real (tho perhaps indefinite mystic hang-up) being pioneer type-operating-on-the-indians-grew-up-around-here-carries-a-machete-and runs-plantation aloneness, real archeological pro.[v]

He also described some of her medical interventions, including operating on a murderer who had sustained gunshot wounds. In fact, his letter is cut short as he and Shields ride off on horses to save someone’s life after they are bitten by a venomous snake. It seems that saving lives was a pretty regular occurrence for her, and her daughter in 1957 called her “a one-woman clinic for the sick in the vicinity of the ranch.”[vi] One wonders what Ginsberg meant by “Ugh.” It seems that he may not have been impressed by her book (a children’s novel based on her own childhood) but there is no evidence that he ever read it. The term “authoress” seems somewhat condescending and “nutty” and “tiresome” are hardly enthusiastic endorsements of her character. Even so, her weird and wild side clearly impressed him.[1]

Ginsberg also wrote to his former teacher, Mark Van Doren, and mentioned Shields. He wrote:

working on a plantation of a woman who used to play Jane in the Tarzan pictures around 1933 (Karena Shields), a religious minded grandmother now who preferred to hide her face with wrinkles multiplied.[vii]

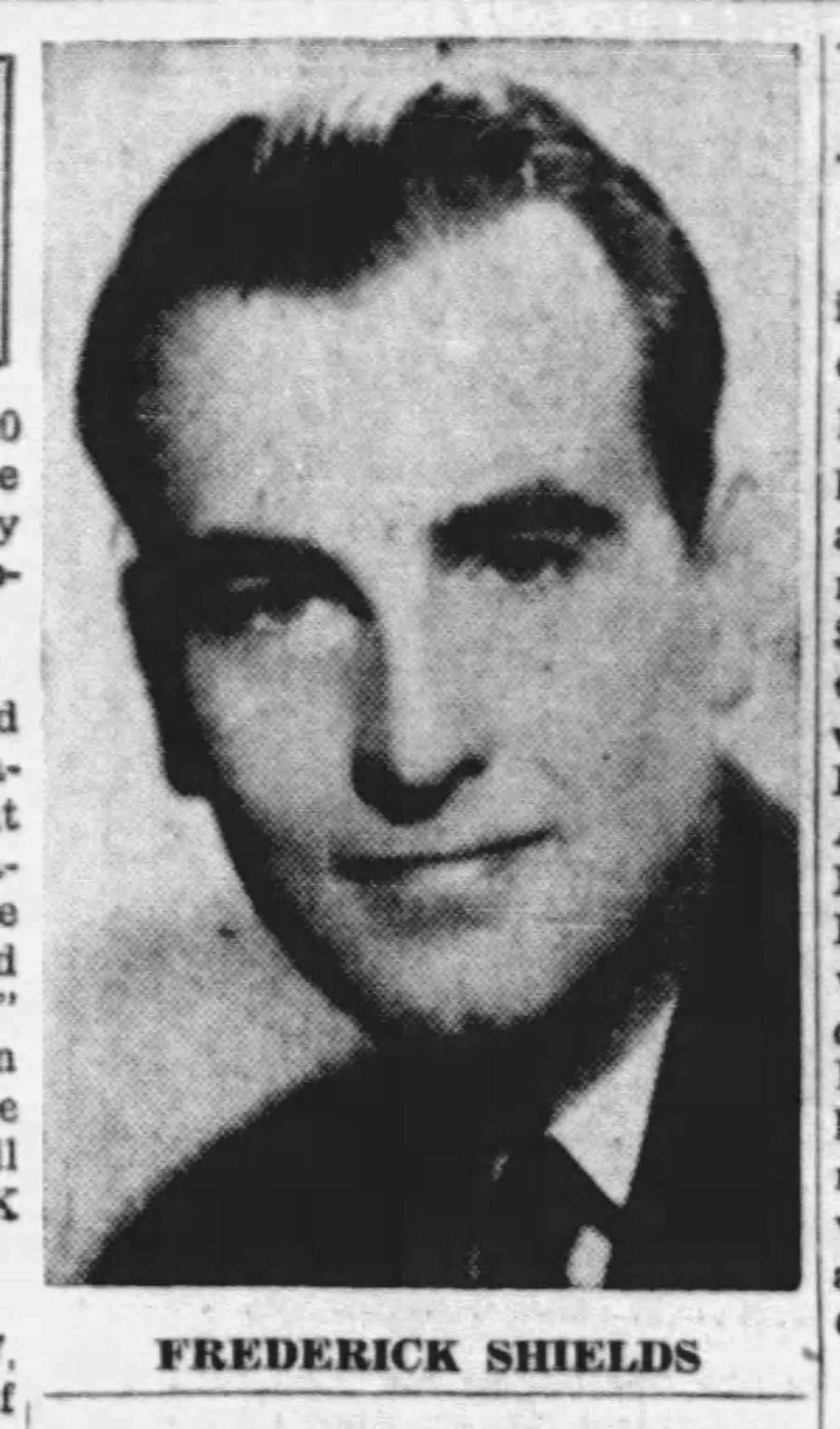

The claim about her being “Jane” in a Tarzan movie has been repeated by a few of his biographers and it’s something Ginsberg doubled down when annotating an old photo of him in the jungle. He said she was the “first Jane in 30s Tarzan movies.” This is another good example of why we ought to be careful taking Ginsberg at his word. I don’t think he was deliberately misleading anyone, but Shields was never in a Tarzan movie. She had played a minor role in one episode of a Tarzan radio show directed by her husband, Frederick Shields. As we will see later, she was an actress but Ginsberg’s claim here—one of the few facts about Karena Shields that seems widely known—is entirely false.

As for her being a grandmother, it is worth keeping in mind that she was only forty-nine. Her eldest daughter was about twenty-four and unmarried, making it unlikely Shields really was a grandmother by then (though certainly not impossible). Still, Ginsberg’s remark makes it seem as though she was extremely old. The comment about hiding her face because of wrinkles may well be true. Throughout the thirties and forties, she was considered extremely beautiful and was famous in part for her looks, so perhaps she struggled with her image at this stage, becoming self-conscious.

Ginsberg stayed with Shields from January through to May, borrowing money from her so he could get to Mexico City and then back to the U.S. He headed to San Francisco and settled there for about two years, where he would write possibly the best and certainly the most famous of his poems. (See this essay for details about his first ever poetry reading.) John Tytell, author of numerous books on the Beats, including one of the first critical studies, believes that Ginsberg’s time with Shields was pivotal for his poetry:

Living on a plantation in Chiapas, Mexico, became a transformative experience, opening a doorway to the discovery of an authentic new voice. “Howl” was to be its first expression.[viii]

In all accounts of Ginsberg’s life, leaving Shields’ finca marked the end of their relationship but in fact that was not true. They kept in touch and in the summer of the following year, 1955, she visited him in San Francisco. We will see in the next section that Shields mostly lived in California, travelling to Mexico in the summer months, but it appears that during the mid-fifties, she was doing the opposite. One of her daughters got married on August 11, so that most likely accounts for her trip, but Shields travelled regularly to lecture and seems to have given a few talks in California that summer. She also wrote articles for the Los Angeles Times in June, July, and August of that year. Given how remote her finca was, she almost certainly submitted these when in the U.S.

In any case, Ginsberg wrote about her again in letters to Jack Kerouac. He mentioned her several times that year, trying to encourage his friend to visit her. The first such letter said:

Perfect Forest for Bhikku solitude is near Palenque, skirts of unexplored interior Guatemala Peten Rain Forest. Where I stayed at the Shields finca, you can go clear mountain water and solitude and hammock and grasshut for nothing, maybe free food too. When the time comes let me know, I’ll write the Signora, maybe probably in fact surely she’ll set you up a grass hut alone at village outskirt in the midst of forest.[ix]

Ginsberg hoped the jungle solitude would do for Kerouac what it had done for him, but whilst Kerouac was initially enthusiastic, he later changed his mind. From Mexico City, he wrote, “I don’t want to see the Senora—I won’t move from Bill’s pad. I am hungup and very high on Mexican.”[x] Kerouac was using various drugs to write Mexico City Blues and although these substances helped him to create, they also damaged his health and made him paranoid and depressed.

As best I can tell, Kerouac never did meet Shields. If they had, they might have discussed Robert Giroux and Harcourt-Brace, as they both shared the same editor and publisher. Shields talked about this with Ginsberg and expressed her frustration with Giroux in particular. He quit Harcourt-Brace that year and whilst he promised to help her send a manuscript to other publishing companies in New York, he instead went to Europe and left her more or less unable to find a home for a book she had previously assumed he would publish. Ginsberg, then an unpublished young poet who had only just given his first reading, offered to act as her agent—something he had done with friends such as Kerouac and Burroughs. Alas, only two letters from Shields to Ginsberg can be found in his archives and there are none from Ginsberg to Shields.

It is noteworthy that Shields’ letters to Ginsberg are quite intimate and hint at long, deep, spiritual conversations they’d had in person. She makes reference to parts of his psychology that he normally reserved for his therapists, journals, and closest friends. In the last saved letter, she tells him “you have to believe in the possibility of your own blessedness before anything else.” From her responses, we can see Ginsberg was keeping her abreast of his own poetic developments and she was sending him her poetry, which she knew he would not like for it was comparatively conventional. (“It is a bit Robert Frost-ish,” she warned.) In what seems to be her last letter to him, she writes to say he’s welcome to return for “another look at Xbalba.”

It is interesting that she writes “Xbalba.” As some Beat biographers and historians have noted, Xibalba was the indigenous name for the area around Shields’ finca, but it’s a name that Ginsberg got wrong when he wrote about it. He began work on a poem called “Siesta in Xbalba” when staying there and even after he later learned of the correct spelling, he stuck with “Xbalba.” This is odd because although he was bad at spelling and often got placenames wrong, he was happy to change them to the correct form later. See, for example, his misspellings of places in Southeast Asia, discussed in this essay. I think the fact that Shields herself used “Xbalba” is probably why he did not later revert to the more standard transliteration. She was, for him, the true expert on local matters.

In the summer of 1956, whilst working at sea, Ginsberg mimeographed copies of “Siesta in Xbalba” and sent them to friends. Some call it his first book as it predates Howl and Other Poems by several months. (However, there were mimeo’d versions of “Howl” at both the 6 Gallery and March 18 poetry readings, so if we are to consider such publications “books,” then it was not his first.) The front cover of this work featured the words “dedicated to Karena Shields” and later, when it was published in Reality Sandwiches and his Collected Poems, it said “for Karena Shields.” He may not have included her in any poems, but he dedicated at least one to her. Whilst he was not happy with the poem, there can be little doubt it was an important milestone in his poetic career. Later that year, she was also on the list of people to whom he intended to send copies of Howl, alongside the likes of Henry Miller, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, and Ezra Pound.

I can see almost nothing else about Shields in Ginsberg’s writings, nor can I see any mention of him in her writings, but in the 1980s, long after Shields’ death, her grandson David Bryant wrote to Ginsberg. Bryant was an aspiring poet, frustrated by years of rejection slips. “I am Karena Shields’ grandson and I’m afraid I’m exploiting the friendship you had with her,” he wrote, requesting “critical comment” on his work in the hope that he might improve. It doesn’t appear that Ginsberg ever responded, though, and if he did, there was no further communication.

That pretty much covers Karena Shields’ life as it intersected with Ginsberg’s but how much of what he said was true? And what of the loose ends in these threads of stories? What happened to their agreement for Ginsberg to act as literary agent? What letters were not saved? Did such a close friendship simply die away as Ginsberg—from the end of 1955—rapidly ascended to literary stardom? If they did drift apart, was it due to their very different temperaments and interests? After all, Shields was a much older religious woman, extremely anti-communist and quite conventional in writing style, obsessed with ancient history and Ginsberg was about to find himself at the heart of a vibrant arts scene populated by the young and the rebellious.

Much of this is impossible to answer but in the next section I will attempt to explore Karena Shields’ life as a means of determining how much of what Ginsberg said about her was true. If you have read his often exuberant letters and journal accounts from his Mexican trip, it should be obvious from his gleeful depictions of his personal heroics that he was exaggerating somewhat, swept up in the romance and adventure of life south of the border. One cannot prove it definitively, but his stories have more than a little fantasy to them… It certainly would be a reasonable assumption that his accounts of Shields contained similar distortions. As we have seen already, he believed her to be an archaeologist and movie star, and she was neither. However, she was a scientist and actress, and she did seem to represent an archaeology department on certain of her voyages. As for being a best-selling author, she wrote very successful and nationally distributed books. Now let’s see how the real Karena Shields holds up by comparison…

The Life of Karena Shields

Part 1: Catherine, Caterina, and Catty

Karena Shields was born Catherine Mary Plant in Lorain, Ohio, on June 14, 1904.[2] Although one might assume from Ginsberg’s letters that she had been born in Mexico, and it seems she either made this claim later in life or perhaps journalists simply assumed it, she was in fact born in Ohio. Her parents were William David Plant and Jeannie Osgood Plant.

In 1911, Catherine—who as a child seems to have mostly gone by the name Caterina—moved to Mexico with her family, travelling mostly overland but part of the way across the Gulf of Mexico. Her father would be the manager of a rubber plantation in San Leandro, the same place Ginsberg met her fifty years later. Although Ginsberg said her family had owned a $3 million-dollar estate that included many lost cities, and again numerous reporters later made this claim, in fact her father was merely the manager.[3] It also seems the plantation land merely bordered Palenque. William Plant had invested some money into the Chiapas Rubber Plantation and Investment Company, but it was not his company and he was simply there as an employee, as this document shows:

He seems to have taken the position in 1908, travelling back and forth between the U.S. and Mexico until the plantation was ready for his family to visit. Caterina, meanwhile, lived in California with her mother and sister. Of her father, Shields wrote later:

my father came to a determination to live as he thought a man was meant to live: to build a kingdom of his own, to taste life fully and freely, and if need be to go to the ends of the earth to do it. He was not running away from anything or trying to prove anything. He was certainly not seeking security, for he was one who found his greatest security in a freedom that had in it no “security” at all—an open road, an unknown wilderness where he could do as he pleased, provided it was done with courtesy and he hadn’t forgotten to raise his hat to the spirits that dwelt there.

The time came when intention and opportunity met. Some ten years after his marriage, Father came home one day with a pronouncement. He had been offered a position as manager of a rubber property in the jungle hinterlands of Chiapas, bordering on the Guatemalan highlands, and he had accepted it. And thus in one morning the lives of all of us—my mother, my sister, and me—were changed profoundly and forever.[xi]

Alongside this description of her father, Shields mentions his uncle being an explorer in Bolivia, charting unknown rivers, and mentions his friends at the University of Michigan, with whom he had vigorous discussions about the universe. It seems much of his personality was inherited by his eldest daughter.

In 1911, when Caterina was about seven, she moved from the United States to the jungles of Mexico, not far from the Guatemalan border. With her was an older sister, their mother, and a Chinese cook. They had more than eight hundred Mexican labourers. She later wrote two books about her childhood in the jungles of Chiapas: Three in the Jungle (1943) and The Changing Wind (1959). These are both novels but they are prefaced by statements claiming that everything she wrote was true and the latter book makes claim to her “photographic memory.” These are indeed vivid, engaging books and Shields was a gifted writer. It is impossible to say how much is true, and she admits to highlighting parts and skipping others as any writer necessarily does, but certainly one feels that much of the content is based on real experience. Both books are well written although the earliest one is aimed at children and as such is more basic in terms of language. If you are interested in Shields’ childhood adventures, they are each worth reading. The second book could perhaps be said to resemble Chinua Achebe’s masterpiece, Things Fall Apart, in as much as it depicts the ending of a culture as modernity and Western civilisation bear down upon an ancient people.

Shields claims her family lived on the rubber plantation for about six years before returning to the United States, but her father died in the U.S. in 1916, five years after they first moved to Mexico.[4] As with so much in her life, the dates simply don’t add up. In any case, she grew up in the jungle, among the local children of the nearby Karivi tribe. She was educated alongside her older sister and was apparently intelligent enough to learn lessons aimed at pupils several years older than her. Her education here partly came from indigenous people and she learned about their mystical and cosmological beliefs. It seems from her later writing that she did not come to believe these (in spite of Ginsberg’s using “mystical” several times when describing her) but certainly her father instilled from an early age the idea of respecting even those beliefs you do not share, and into adulthood she wrote and spoke about them with interest and respect, though her own beliefs were Christian and her education was scientific. The belief systems of these people would give her much to write about later in life, sometimes in academic papers and sometimes more accessible magazine articles.

She enjoyed her childhood in the jungle but it did not last long. Various events precipitated her departure, including a collapse in rubber prices and regional instability that posed the threat of violence. Shields points to the felling of a culturally significant tree in The Changing Wind. She thus had a very unusual childhood and clearly this impacted the next years of her life. A few decades later, she would tell people that she felt “alien” in the United States and was more at home in the jungle, which is why she spent the rest of her life divided between American and Mexican homes. This is one of the themes of The Changing Wind. Although not native to the region, young Caterina feels more at home in the jungle than the United States.

Caterina—who switched to become “Catty” as a teenager—and her family lived in California upon returning to the States. She attended Arcata High School in Northern California, and in her yearbook (pictured above) it is noted that she spoke often of her time in Mexico. Already, one can see literary aspirations as she not only edited the yearbook but contributed a short story about life in the Mexican jungle. It featured a “poisonous” snake and a man called “Bartolo.” That was the name of a man Karena knew during her childhood in Mexico. When she first arrived at the finca, she was carried on his back. For the rest of her life, she would retell this and other stories.

After high school, Shields went on to obtain a number of qualifications although it’s hard to pin down exact details. She obtained a Bachelor of Science degree from San Jose State College, a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Southern California, a Master of Arts in Anthropology from the University of Mexico, and then a Doctorate of Medicine from the University of Mexico, Institute of Tropical Medicine. A number of newspapers in the 1920s and 1930s mentioned that she was a graduate of Stanford though no details are given. One 1946 report says she got her teaching credentials at San Jose and then did her “education degree” at Stanford. As with much in her life, it is hard to confirm these details and what documentation exists is often confusing or even contradictory.

It looks like Shields was in her final year of high school in 1922 and presumably obtained her B.A. from either the University of Southern California or Stanford in the years that followed. By 1927, she was working in Kansas City in a variety of roles concerning drama. After moving from California late that year, she began working as “expression instructor” at Northeast junior high school, where she directed many plays. She also acted in a number of plays, once fainting on stage, earning her a front-page mention in The Kansas City Times. She worked as “dramatic director” for W.D.A.F., a local radio station. A few news articles hint at other positions (directing shows for children and women) and it’s not entirely clear whether those are true or whether the reporters either made assumptions or were fed false information by Shields. One suggested she had been an experienced stage actress on the East Coast and others gave her more experience directing radio programmes than she really had. One article said she had appeared in a movie with Wallace Reid but I see no record of that and he died when she was still a teenager, making it quite unlikely. However, if she had appeared in one of his final films, it might have been when he played the role of a man named William Burroughs in 1922…

Although documentation is hard to come by, it seems she married a man named Frederick H. Shields in 1928 and by 1930, they had a child called Evelyn Jean. That same year, she moved back to California and stayed with her mother, who still lived there as a widow.

Part 2: Karena

From 1930, the name Karena Shields was regularly in the newspapers as she embarked upon a career as an actress. Ginsberg had claimed she played Jane in a 1930 Tarzan movie but that is not true. She played the role of “Helen” in episode two of a Tarzan radio series directed by Frederick. In fact, she played many roles in radio shows written, directed, or produced by her husband. However, before you assume she was merely helping her successful husband, I should mention that he likewise acted in radio plays she wrote, directed, and produced. Evidently, they made a good team. Her plays included “The Sheriff” and “Custard Cured.”

Karena Shields seems to have lost interest in acting after several years and her life took a very different turn in the mid-1930s. In 1935, she received her pilot’s license and from 1936 on she was known across the nation as an “explorer and aviatrix.” She had 250 hours of flight time logged by then and set out on her first long voyage, spending six months in Central America, taking photos from the air and exploring on foot. The American press made much of this attractive female adventurer. According to The Los Angeles Times, she was “the first American woman” ever to visit “Maya country,” an idiotic claim in part because Shields had lived there with her mother as a small child. Still, numerous media outlets repeated this and similar claims, often suggesting that she was among the first white people to visit the region, sometimes with the suggestion that all previous white people had disappeared or been killed by the “dark natives.” The press seemed to want a new hero and the Los Angeles Times wrote in December, shortly after her return to the U.S., “We may have another Amelia Earhart here.” Earhart, whom the media also described as an “aviatrix,” disappeared six months later.

In spite of the intense media coverage, it is unclear how often she went to Mexico and how much time she spent there. A much later news article claimed that by 1945 she had made three trips to Mexico since 1932, when she first went back as an adult. This is surprising because the media between 1936 and 1945 heralded her as an explorer who divided her time between homes in Los Angeles and Chiapas. They seemed to imply that she spent about half of her time in each place. That same year, another newspaper claimed she had just returned after fifteen full years in Central America! The first of these also stated that she rented planes rather that owning one, which was inferred by most reports. All accounts agree that she would fly from Los Angeles to somewhere in Southern Mexico and then proceed by land to her childhood home because there were no suitable landing strips nearby. Given how frequently she spoke with the press and talked in public, it is surprising that reporters were unable to agree upon basic details. In any case, it does seem that she lived mostly in the U.S. and visited her finca on occasion.

The fact that she returned to her childhood home should be a surprise given that her father had merely been the manager of the plantation and that he had died in 1916. There is very little information available on this subject and again what can be found tends to be unclear or contradictory. Reporters seem to have assumed that the family had always belonged to her family, but that’s not true. It had been owned by the Chiapas Rubber Plantation and Investment Company from 1899 until around the time the Plant family left Mexico and ownership reverted to the Mexican government. How then did Karena Shields come to own 75,000 acres of Mexican land, including the ancient Mayan city of Palenque? These were facts cited again and again without explanation.

The simple explanation is that it wasn’t entirely true. The original land had been 24,000 acres and had merely bordered Palenque (although possibly it included other sites of interest). After some years in the U.S., Shields went back to Central America with the intention of starting a chocolate plantation and flew around looking for suitable locations, eventually returning to her childhood home, which she purchased. How a teacher, actress, and writer—not exactly professions known for their high salaries—came upon the money required for such an investment is unknown, but it is important to note that she did not buy the whole former plantation. What Ginsberg and everyone else who ever wrote about her failed to mention, aside from one book about Palenque, is that she only bought the 200 acres that immediately surrounded the family home.[xii] (It does seem her father had owned various properties, so perhaps she had inherited a substantial amount of money from him.)

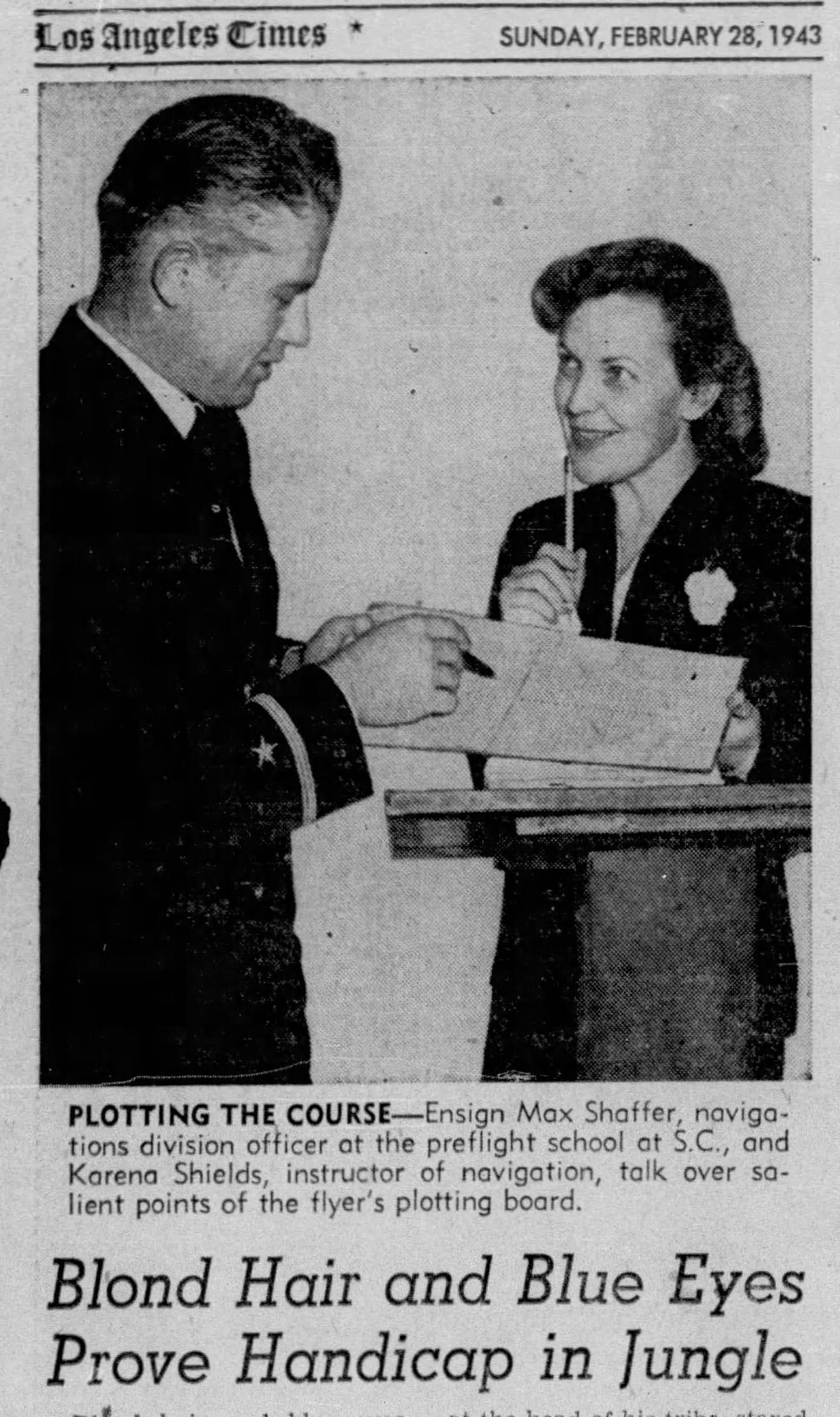

Questions also abound over the planes she used and her role as a pilot. The media made much of her being a heroic “aviatrix,” but on one of her first big journeys, she sat beside a male pilot, saying that she would buy a plane in Mexico City and fly the rest of the way. Sometimes, she told reporters she rented planes when she needed one, and this is possible, but passenger lists show that she flew on commercial flights from Mexico City to Los Angeles. I don’t mean to suggest that she was lying because later she taught flight navigation to naval cadets, so obviously she was qualified. Perhaps the reason for these apparent contradictions was that, on these journeys, she had her children with her and so it seemed a safer means of travel for those particular trips.[5]

I was also able to find little information about her personal life but by the early 1940s, she was divorced. There are no records of this but at a certain point she began being referred to as a divorcée in news articles. She kept her ex-husband’s surname and for the rest of her life was “Karena Plant Shields” or “Karena P. Shields.” Note that she had evolved from “Catherine Mary Plant” to Caterina, Catty, and Karena… This was a woman who changed interests and seemingly shed parts of her past when it suited her, providing herself a new name, changing her date of birth, taking on new careers and hobbies, and—as we shall see—finding areas to excel in.

Shields was often referred to as an “explorer” and this was something very much played up in the media. It came from the fact that she framed herself as an intrepid explorer of Mayan ruins. She first did this in the mid-1930s, spending about a year visiting these historical sites, and when she returned to the U.S. in late 1937, she gave many lectures on Mayan history, mixing academic discovery with exciting tales from the jungle. At this point, one finds much sexism in the news reports on her activities. There are invariably headshots of her looking quite attractive and then lines like this:

Miss Shields, in spite of her more than man-sized job, is young, beautiful and charming, it is said.

Another cringe-worthy article referred to her as a “Blonde Goddess,” even though when interviewed she was adamant that being blonde and blue-eyed made her little more than a “freak” in the eyes of the local people. The same report referred to “murderous and hostile natives” despite her explaining that there was nothing particularly dangerous or uncomfortable about life in that part of the world. In those days, racism was as common as sexism in the newspapers. Many articles about her included crude slurs and sometimes even offensive cartoons depiction horrible stereotypes.

As her celebrity grew over the next years, almost every account contained some flattering remarks about her appearance, with few reporters failing to mention that she had a lovely smile. Some called her “frail,” many said she was “petit,” with most noting she was blonde with blue eyes, contrasting this against the darkness of the “natives” she encountered in the jungle. One absurd news report said she was “organizing an expedition to penetrate the Central American jungle in search of a tribe of Mayan giants, long reputed to exist there.” Another seems to suggest she was in search of Atlantis. In a sense, the public wanted much the same as they had gotten from the Tarzan radio show she had acted in back in 1930.

She continued to give public talks about the Mayans and her own adventures. Here’s what one news report from 1939 said:

Miss Shields, reared in the shadow of ancient Mayan ruins, had no contact with white women, save her mother and sister, until 15 years old when she came to California and enrolled in Stanford university.

She became interested in the theater and later was a featured artist on the radio. But Miss Shields longed for her jungle home, its thatched hut and the freedom of life on a 75,000 acre cacao [sic-cocoa] plantation, so she studied aviation, became a pilot and now flies her own plane from Hollywood to the jungle.

It makes for an incredible story… although one must acknowledge the false claim in the first paragraph about spending the first fifteen years of her life in Mexico. Other reports say that “only five white men” had ever set foot in that part of Mexico, and most mentioned the “dangers” of the jungle.

Had Karena Shield perhaps spread this false information to the press to promote herself or had reporters made assumptions about her? Reading all these hundreds of news reports, I wondered at times whether she was a master manipulator of the media. I don’t mean to suggest she necessarily deceived in a deliberate way, but I wondered whether—like Allen Ginsberg—she knew how to spread a message and perhaps exaggerate some things and downplay others. Was she particularly attuned to the American public and aware of how to arouse their interests in such a way that it would afford her certain opportunities? Her books and other writings seem very reasonable but statements attributed to her and repeated in the press suggest a flare for the dramatic. The repetition and distortion of certain claims suggest that they came from Shields herself, including the abovementioned “five white men,” which sometimes became five expeditions. Sometimes they all died and sometimes they were the only ones who’d attempted to visit that part of the world. Finally, I found a direct quote from her in a California newspaper from 1946:

The Karives and the other Mayan descendants in this jungle region of the Sierra Madre mountains […] are exceptionally hostile to strangers. Five expeditions, three Mexican and two American, have completely disappeared in the district. One European scientist who managed to survive was taken out utterly mad.[xiii]

This may well be true but it sounds more like fiction. Likewise, her language around this time often seemed designed at entertaining and enticing rather than informing. She once said the following before a major expedition:

The natives there have been warped by something, and practice terrible ceremonies akin to voodooism, which perhaps originally destroyed their civilization.

She also tended to include phrases such as “secret tribes” and occasionally told stories that appeared to depict supernatural phenomena. This was quite possibly as a way of ensuring her efforts received more attention, thereby leading to more invitations to lecture or write for magazines. Such statements and phrasings are incongruous with her apparent affinity for the indigenous people and what seems like a life-long interest in helping them. They are also at odds with her serious scientific inquiries, but perhaps she felt a modicum of sensationalism might allow her more freedom for serious work. One detailed account of a talk she gave in 1937—admittedly early in her career as an explorer, aviator, and academic—suggests she spun stories of lost treasure and believed Central America might be the cradle of human civilisation.

Maybe she was simply a natural storyteller, caught up in the exploratory enthusiasm of the era, who liked to hook her readers into exciting tales. We have seen that she wrote stories, articles, and plays from a young age, and clearly she was a very successful public speaker. (By 1940, she listed herself as “lecturer and author” on government documents.) Like certain popular male authors of the era, she liked to put herself into her stories although not in a particularly egotistical way. She simply recognised the value of a first-hand perspective, especially when detailing cultures and landscapes utterly alien to most readers. Every account of her lectures that I could find highlighted her vivid descriptions and engaging storytelling. One mentioned that she had someone beating a drum as she demonstrated indigenous dances to help the audience visualise aspects of their culture.

By the mid-forties, she was mother to three children and teaching navigation at the University of Southern California’s naval cadet school. At the same time, she was writing her third book, teaching young pilots for the Civil Air Patrol, studying for her master’s degree, and still managing to make the occasional trip to her finca. That book seems to have been Three in the Jungle, a novel aimed at children and heavily based on her own life experiences. Indeed, the character of Caterina is clearly her even if the other characters are invented. I’m not certain what the first two books were, but possibly they were put out by small presses or were academic texts.

In 1948, Shields went on another expedition, this time taking along her eleven-year-old daughter and a young boy. She was now working as a professor of humanities at the University of Redlands and flew to the southernmost tip of Mexico with the aim of proving Mayan civilisation was a thousand years older than previously believed. When interviewed by the Los Angeles Times about being professor of humanities she gave an odd reply: “There’s nothing extraordinary about an archaeologist. He’s just a super-duper detective who deduces the secrets of man’s past from clues.” As we have seen, she was not an archaeologist but seems to be claiming that she was and doing so in oddly childish language. Why exactly was she so often referred to as an archaeologist? Sometimes it seems reporters weren’t entirely sure of the distinction between archaeology and anthropology, but that doesn’t explain everything. A 1947 article called her “a recognized archeologist” and many others by well-educated people say that she was, if not a professional archaeologist, then someone working within that field. Perhaps this can be explained by a quote from a 1943 news report:

Mrs. Shields went with the coaching and blessing of Dr. A.O. Bowden, head of the University of Southern California anthropology department, and represented Tulane and the University of Pennsylvania archeologists.[xiv]

Again, it’s not clear what relationship she could have had with those places but evidently she had their trust. Perhaps her expertise in other fields, coupled with the difficulty of sending genuine archaeologists, meant that she was trusted to make and send back reports from her various journeys.

In the 1950s, Shields’ fame declined. Perhaps she had been so widely celebrated because of the apparent incongruity of her appearance and vocations. Certainly, the media fawned over her and made that quite apparent. Or maybe she stopped yearning for fame. It definitely seems as though she had made deliberate efforts to become a public figure and maybe after achieving real respect—a celebrated writer, professor, and explorer—she no longer felt the need to push herself into the spotlight. Or maybe it had something to do with a comment Ginsberg made about her wanting to hide her aged face. The newspapers in the thirties and forties had been filled with the picture of a youthful blonde, but now she was around fifty, she might not have held the same appeal or wanted the same attention.

We know from Ginsberg’s account that she was on her finca in early 1954 and then in San Francisco in 1955. She was also writing long essays and articles for reputable publications throughout much of this time, including many stories for the Los Angeles Times. Her style was personal (writing as “I” and “we”) but authoritative. She wrote as though she expected readers to know who she was even though there was seldom any context provided. Her stories concerned the politics, culture, and history of Mexico and she was often an active participant, detailing her own inquiries as she asks local people about bigger issues and reports their speech. She liked to throw in stories about being shot at to spice up her narratives (which again supports the idea that perhaps she had created a sort of personal mythology via the press in previous decades). Often, she recounted stories from the finca and these were sometimes the whole article. In several, she talked about practising local witchcraft to help sick indigenous people. Her stories were filled with action and dialogue, suggesting that she wanted to write fiction but found her own life made for the best material. Even her great novel, The Changing Wind, was not really a novel. It was just a memoir of sorts.

In the sixties, she largely disappeared from the headlines. By all accounts, she continued to write and teach and give occasional lectures, but she was no longer the heroic adventurer. Perhaps the world had opened up too much for that, or maybe she was just now too old. She was, after all, approaching sixty. Stories appeared, such as “Confessions of a witch doctor,” in 1961, but she was re-using old material. She worked as a professor of anthropology (again, many sources mistakenly say “archaeology”) at U.C. San Diego from 1958 until her death but continued to spend summers on her finca in Southern Mexico. This was not for relaxed vacations but because her home functioned as a medical centre at which she was the only doctor. People would travel for miles to seek her medical skills whenever she returned, and she continued flying her plane to even more remote locations to give emergency treatment. She did this at great risk during times of local violence and continued right up until 1972, when she passed away. She also continued writing and lecturing until the end of her life.

Snakes were a feature of Shields’ life from a young age. As a little girl, they were the first thing she saw entering the Chiapas finca where she would spend her childhood, the locals having killed as many as possible and hanged them along the path to the house. Her first published writing was about a “poisonous snake” and she wrote many more stories that featured these creatures. She had even given traditional snake dances in the United States, explaining to audiences that they were the “children of time” according to the Mayans. These creatures appeared in her books and she often saved people’s lives after they were bitten. When Ginsberg wrote about her in a letter to Kerouac, his story was cut short as they dashed off to help a snakebite victim. Again and again, reporters spoke of her bravery living in a place so infested with dangerous creatures… and eventually, in 1972, it seems one of them finally got her. There is no clear record but an obituary published soon after her death says that something—most likely a snake—bit her whilst she was at her finca. The other people present attempted to transport her back to the U.S. for treatment but she died in Mexico City.

Shields may have become less of a media darling towards the end, but she was regularly celebrated in the academic world. She received awards and recognition for her work fighting tropical diseases and documenting Mayan culture. When she died, she was working on a new book: The People At The Edge of The World. Since her early childhood, she had been devoted to the indigenous people of that region and worked to help them until her death. I could find not a single reference to her in the news after her death, showing how quickly she had been forgotten, which is a shame given she had led such an incredible life and written so much in so many styles and on so many topics. She deserves to be remembered and I hope this essay has helped in some way. I also hope that one day her book, The Changing Wind, is republished, for it is certainly worth reading. Likewise, the articles about her talks say she took many photos and it would be wonderful if these could be exhibited.

Footnotes

[1] Compare the depiction of Karena Shields here to the female Dr. Cotter in the recent movie adaptation of Queer. One wonders if Luca Guadagnino had Shields in mind when gender-switching Burroughs’ Dr. Cotter for his film… It’s a stretch, but his Cotter seems closer to Shields than to Burroughs’ Cotter.

[2] Her year of birth is far from clear. Various documents show that she was born June 14, 1904; however, others show June 14, 1907. It seems that as a child, for some reason, she was listed as having been born in 1904 or 1905; however, in adulthood she mostly said 1907 and sometimes 1905. Her given age in later censuses and news reports suggests 1907 but early immigration paperwork and government documents say 1904 and 1905. Sometimes in later life, she also seemed to suggest 1904. When her family travelled to Mexico in 1911, she was listed as being seven years old, but in her memoir, she explicitly states she was three. The likeliest explanation is simply that she wanted to appear younger than she was, especially when she reached middle age, and so she shaved a few years off her date of birth.

[3] Interestingly, in Shields’ book, The Changing Wind, she says that the plantation was valued at $3 million dollars when the family left Mexico. Shields also refers to her mother in the book as “La Senora, queen of” the finca, which is what Ginsberg called Shields in the letters quoted above. I wonder then if he had read her book and picked up on these details.

[4] An article in an aviation journal suggested she moved to the U.S. after her father’s death. This differs from accounts in her books, but those are technically novels even if extremely autobiographical.

[5] Yet another odd point is that she had three daughters but on some of these flights she had five daughters with her, suggesting that she had flown children out of Mexico under the pretence of them being her own children. Clearly, there is again some important piece of information missing.

Endnotes

[i] Journals Early Fifties Early Sixties, p.51

[ii] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.206

[iii] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.206

[iv] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.207

[v] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.211

[vi] The Waco Times-Herald, June 26, 1957

[vii] Naked Angels, John Tytell, p.99-100

[viii] Beat Transnationalism, John Tytell, p.120

[ix] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.279

[x] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.318

[xi] The Changing Wind, p.14-15

[xii] Palenque: Eternal City, p.252

[xiii] The Peninsula Times Tribune, November 29, 1946

[xiv] The Los Angeles Times, August 24, 1943

brilliant research as always, David. That must be her in Ginsberg's photo that you link to at the NGA website, right? that's never crystal clear from his captions but based on the other photos here, it seems it has to be. Thanks as always!