The Berkeley Town Hall Reading

Remembering one of the most important nights in Beat poetry on its 69th anniversary.

Sixty-nine years ago today, a poetry reading took place in Berkeley that many Beat historians refer to as a “repeat performance” of the 6 Gallery reading that occurred some five months earlier.[1] It was another resounding success and helped push those young poets, who were quickly becoming local celebrities, towards a greater degree of renown.

Whereas the 6 Gallery reading seems not to have been recorded,[2] there exist several photographs and audio recordings of the so-called “repeat performance.” It is fascinating, then, that people still manage to get so much wrong when describing it. Unlike the 6 Gallery reading, the details of the March 18 “repeat performance” are quite easy to uncover. One can, for example, listen to most of the reading in the comfort of their own home by using the Stanford Digital Repository (see the endnotes for specific URLs). Alas, early Beat historians, lacking such convenient resources, made some big errors and others have simply quoted them in later works, trusting that the earliest scholars somehow knew best. As I’ve said before, this is a big problem in Beat Studies and one we must work to overcome.

This essay is spun off from my forthcoming book on the 6 Gallery reading and is based on a wide range of sources. It will set out the basic facts and explain what really happened on March 18 so that people no longer need to rely on inaccurate or incomplete earlier accounts. There will be a little background and also a very short section at the end of this essay that explains why so much of what has been reported before now was wrong. I have tried to avoid too much discussion in the body text and confined those parts to footnotes.

The essay is structured as follows:

Background information

Information about the process of organising the Town Hall reading

An account of the reading itself

A short explanation for why there are so many errors surrounding this event

If you are interested, you can also read more about the mystery and mythology of the 6 Gallery here.

Some Background Information

On October 7, 1955, six poets took to the tiny stage at the back of the 6 Gallery at 3119 Fillmore Street in San Francisco and gave a stunning poetry reading that forever changed not only the local poetry scene of that city but arguably American literature. Five of those poets read and, of them, only one really had any experience or reputation as a poet. (Aside from Lamantia, they only had a handful of readings and publication credits between them.) The other poet on stage was Kenneth Rexroth, who acted as “introducer,” to borrow Allen Ginsberg’s phrase.

Philip Lamantia read some work by his deceased friend, John Hoffman, and this was followed by performances by Michael McClure, Philip Whalen, Allen Ginsberg, and Gary Snyder. Each of them gave a successful, well-received reading, but of course it was Ginsberg’s reading of “Howl” that stole the show. Over the next few months, all of these poets except Lamantia—who was going through something of a personal, spiritual transformation—gave more readings around the city, including at the newly formed San Francisco Poetry Center.

San Francisco and the wider Bay Area had possessed a vibrant poetry and arts scene prior to this but wild poetry readings were uncommon. Also, it is of tremendous importance that the young, inexperienced poets on stage at the 6 Gallery, who would soon be identified as forming the nexus of the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance, were largely newcomers to the scene and the city’s most renowned poets—Robert Duncan, Kenneth Patchen, Jack Spicer, Robin Blaser—were all absent. It was not so much the birth of a new movement as the overhaul of an old one.

It is also worth noting that some of the poets on stage had only recently met one another and some were meeting for the first time. Ginsberg had arranged the event with the help of Rexroth, who had put him in touch with his protégé, Snyder. Snyder had invited his old pal, Whalen, and Ginsberg had enlisted McClure and Lamantia. In the audience were the likes of Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. A great many friendships were formed that night, leading to the expansion of the Beat Generation and a number of productive partnerships that would last for decades.

Over the next few months, these poets spent a great deal of time together, writing and drinking and goofing and fornicating. They collaborated to some extent, helping each other revise their poems and inspiring each other to write new ones. They read often in the bars and cafés and galleries of the Bay Area, but only individually or in pairs. These were events held in small venues and they were not widely promoted, but the crowds tended to be enthusiastic and word quickly spread of the poets and their provocative work, with “Howl” gaining the most notoriety. People wrote letters that were sent across the country and around the world, talking about an exciting new movement. Composed Jack Goodwin, for example, wrote in December 1955 about “Ginsberg and his chorus of howling boys […] virtually march[ing] in formation”[i] from one venue to another, drinking and reading poetry and screwing almost anything that moved.

In February 1956, these poets and their friends began to plot another reading and this time it wouldn’t just be one or two poets on stage, nor would it be—as was so often the case—an impromptu reading for the enjoyment of a random assortment of drunk artists. This would be the biggest reading yet and people would bring cameras and professional recording equipment…

Organising Another Reading

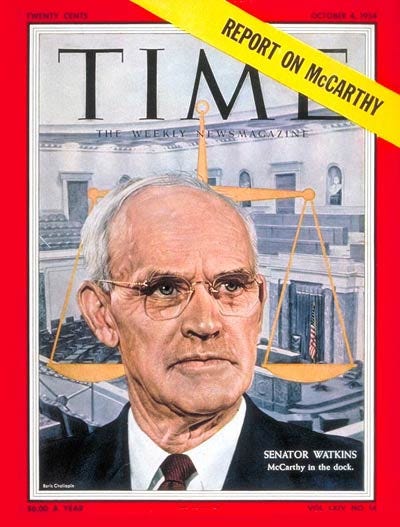

It had been Allen Ginsberg who had mostly arranged the 6 Gallery reading but this time around he shared the responsibilities.[3] He and Snyder planned the event, gathered the poets, and handled most of the promotional work, whilst Thomas Parkinson, a professor at nearby U.C. Berkeley, took care of the logistics. Parkinson had been part of the local poetry scene since the late forties and had been published in Circle alongside the likes of Henry Miller, Kenneth Patchen, William Carlos Williams, Kenneth Rexroth, Anaïs Nin, and Robert Duncan. He would later arrange for Ginsberg to read “Howl” on BBC Radio, defend “Howl” in court when it was charged with obscenity, and edit the first critical study of the Beat Generation, Casebook on the Beat. That was published in 1961, the same year Parkinson survived an assassination attempt when he was shot by an anti-communist former student. He was a fascinating character.

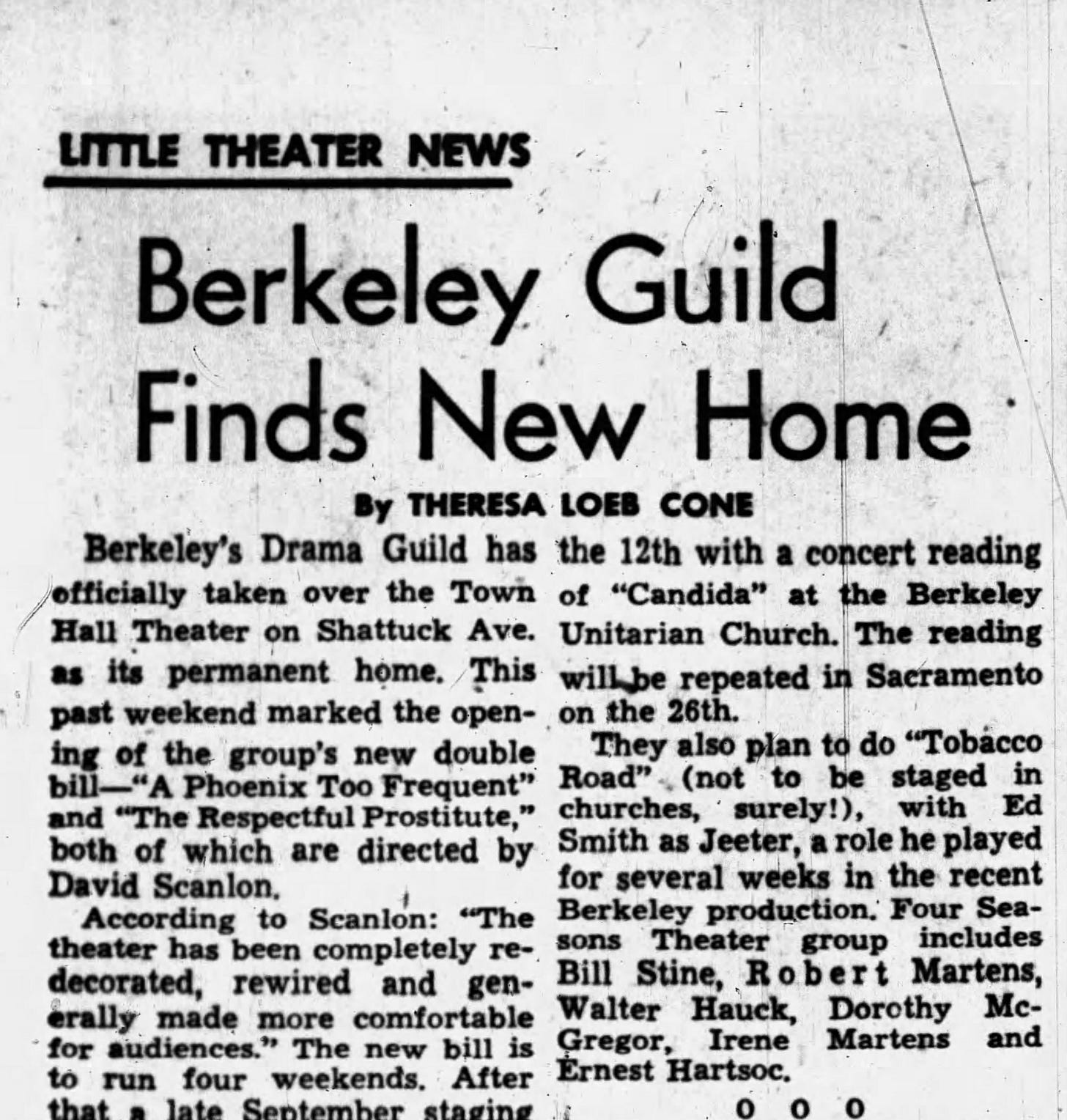

It was probably Parkinson who picked the location for this reading: the Berkeley Town Hall Theater. If you google this term, you won’t find much and what you will find is most likely taken from histories of the Beat Generation that were written by people who had simply read other Beat histories and repeated what they found there. (Or, depending on your location, you might learn all about the town hall in Berkeley, England.) In other words, there isn’t much information available and what can be found is largely hearsay. This stems from the fact that the Berkeley Town Hall Theater existed only for a short period of time.[4]

Located at 2797 Shattuck Avenue, this converted refrigeration warehouse was the home of the Berkeley Drama Guild from its inception in August 1954 to its demise in December 1958. According to a local newspaper, the organization “specialize[d] in in the performances of first productions or generally best plays in dramatic literature.”[ii] (Newspaper advertisements show a mix of classic and contemporary works, with a play by Luigi Pirandello showing the week before the March 18 poetry reading.) The Berkeley Drama Guild took over the Town Hall Theater and immediately renovated the building. “The theater has been completely redecorated, rewired and generally made more comfortable for audiences,”[iii] the director of their first plays told the Oakland Times. They seem to have been quite popular and their performances were well received, but even so it did not last long. In December 1957, a seven-car accident outside the theater resulted in a vehicle flying through the back wall during rehearsals, causing one reporter to quip that their next show would be a “smash hit.”[iv] None of the actors were hurt but the building was badly damaged. It was repaired for an estimated $500 but a year later the Guild disbanded due to a combination of financial difficulties and creative differences between the producers, Robert Ross and Herbert Eaton.[v]

The venue was most likely chosen because of its proximity to U.C. Berkeley, where Parkinson was a professor of English Literature. They also would have needed a much bigger venue than the 6 Gallery, which had been packed to capacity for the unexpected success of the October 7 reading, and Berkeley offered bigger spaces at cheaper rates. The Berkeley Town Hall Theater also happened to be just a half-hour walk or a five-minute drive from Ginsberg’s Milvia Street cottage. Although he often slept in San Francisco at this point, due to his work at Greyhound, his cottage was sometimes used by Snyder, Kerouac, and Whalen.[5]

The fact that this reading took place in a completely different venue and even a different city (Berkeley rather than San Francisco) is one reason why the oft-used term “repeat performance” is inaccurate. Another is that the poets themselves conceived of this as yet another in a run of poetry readings rather than a repeat of their first one. This can quite easily be seen from their letters, including the first one gathered in The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, where one can see the two men were discussing a line-up that really did not resemble that of the 6 Gallery reading. Snyder—who was two months away from a very long-awaited trip to Japan—suggested the inclusion of Japanese music by ethnomusicology professor Robert Garfias and proposed a number of other poets for the lineup. However, they would keep the original group of poets from the 6 Gallery reading, minus Lamantia, who was in Oregon.

On February 24, Snyder wrote to Ginsberg with what one can only assume was a suggestion for the text of the promotional postcard for the event. He wrote:

Good-time poetry / Nobody goes home sad / Ginsberg blowing hot / Snyder blowing cool / Whalen on a long riff / McClure blowing high notes / everybody invited free / free wine / Rexroth on the big bass drum.[vi]

Indeed, the postcard they sent out several weeks later read as follows (with spacing and indentation as best I can accurately reproduce here):

CELEBRATED GOOD TIME POETRY NIGHT

Either you go home bugged or completely enlightened.

Ginsberg blowing hot,

Snyder blowing cool,

Whalen puffing the laconic tuba,

McClure his hip high notes,

Rexroth on the big bass drum.

Small collection for wines and postcards.

Drunkenness, abandon, noise, strange pictures on walls.

Oriental music, lurid poetry.

Extremely serious. Free satori.

Sunday, March 18 --- beginning 8 p.m.

Town Hall Theatre – Stuart and Shattuck, Berkeley

One and only final West Coast farewell appearance of this apocalypse. Admission free.

Some of you may be thinking, “Hold on, I’ve read the postcard text and this is not it!” Actually, it is exactly what was written on the postcards that they sent out prior to the reading. Later accounts have pulled from Richard Eberhart’s “West Coast Rhythms” article and Lawrence Lipton’s The Holy Barbarians (1959), both of which provide a text similar to but different from the above. I suspect Eberhart (or his editors) abbreviated the postcard text deliberately due to space constraints and Lipton merely copied from Eberhart. It is notable that all later versions omit “final West Coast farewell appearance.” This line is a reference to the fact that Snyder was soon to leave for Japan and had recently given readings in the Pacific Northwest with Ginsberg.[6] The line “free satori” is frequently misattributed to the 6 Gallery postcard, an incorrect version of which has circulated for the last 50 years.

The Town Hall Theater Reading

On March 18, Ginsberg held a big spaghetti dinner prior to the reading. He enjoyed cooking for his friends and was good at providing large quantities of food for very small sums of money. Many people stopped by because his cottage was near the Cedar-Shattuck Avenue F-train station, making it convenient for those coming from San Francisco. The guests occupied the single room of his little cottage, and one visitor recalled it being “lit mostly by candles.”[vii] There was wine, too—specifically “cheap red California wine poured from a gallon bottle”[viii]—and just as they had done at the 6 Gallery, both performers and audience members began drinking to get in the right state of mind. The atmosphere was jovial, as evidenced by a photograph from that day which shows Ginsberg in a tree with Robert LaVigne and an unknown woman. They are all laughing and LaVigne is completely nude. Beat historian Ann Charters (then Ann Danberg) arrived with her date for the evening, Peter Orlovsky.[7] The couple arrived too late for food but stood around drinking wine with the others at the cottage.

They all piled into a handful of cars and drove the short distance to the Town Hall Theater. This was to be a multimedia event, and LaVigne had decorated the place with seven-foot-tall paintings that reminded Ginsberg of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Whalen remembers one of them featuring “a naked lady throwing her arms about.”[ix] There were also drawings of Ginsberg having sex with another man. Charters recalls the drawings depicting Ginsberg and Orlovsky, but LaVigne denied this, saying the other man was someone else.[8] Ginsberg referred to the venue as being “festooned with Chinese brush orgy drawings.”[x]

Neal Cassady was once again in the audience; however, his date from the first reading, Natalie Jackson, was not present. She had killed herself in November partly due to Neal’s sociopathic behavior. Her death had devastated Kerouac and Ginsberg, who felt no small degree of guilt for her tragic fate. Whalen recalls Alan Watts being in the audience and this is certainly possible, for he had been a friend of Snyder’s since 1952. Will Petersen, another of Snyder’s friends, was also in the audience. He had been present at the 6 Gallery reading and later wrote a poem about Snyder called “September Ridge,” in which he seems to describe the first reading but in fact mixed together the two events. His poem refers directly to the 6 Gallery and October 1955, but he mentions things that happened at the second one several times. Even the first lines make it clear that he is remembering the Town Hall Theater reading:

You need a goddam passport, Rexroth complained,

but nonetheless crossed over from The City, served

as MC, as coach bringing on the rookies.[xii]

It’s unclear whether Rexroth actually said, “You need a goddam passport” or Petersen was quoting his “letter” from Evergreen Review #2, in which Rexroth said: “I always feel like I ought to get a passport every time I cross the Bay to Oakland or Berkeley.” Possibly, he made the remark at the reading and then again in print. Rexroth quite often re-used what he considered witty or poignant remarks. I cannot find Rexroth saying this on the various recordings of that event but those understandably are cut to highlight the poets’ readings rather than opening remarks.

Rexroth, who was not yet entirely contemptuous of the Beat poets,[9] reprised his role as M.C. Now wearing a white turtleneck rather than his Goodwill suit and bowtie, he began the event by getting the audience laughing. The audio recording is unclear but he stammers and makes various incomplete statements to great laughter. This was partially because both he and the audience were extremely drunk. He seemed to poke fun at either Ginsberg or Snyder (or perhaps Beat poets in general) by referring to a “poet who objects to everything,”[xiii] which also got a big understanding laugh. He was jovial but boastful, wanting his audience to know that whilst the poets were the stars of this show, he was the city’s leading literary voice and he had lived the bohemian life long before they showed up. When talking about Snyder and Whalen, he said that “one of the reasons I like these two cats is that they’ve lived very much the same kind of life that I have except I’ve done more of it.” Even when issuing compliments, he had to present a positive picture of himself.

In stark contrast to the small dais at the 6 Gallery with its little semi-circle of folding chairs, the poets sat on “elaborate throne-like wooden chairs”[xiv] at the Berkeley Town Hall Theater, a nod perhaps to their vastly enlarged status. A photo shows at least one of these chairs having an armrest carved in the shape of a snarling lion. The audience, meanwhile, sat in old chairs taken from a cinema. Above the poets was “a small row of lights that could be turned on in wild flashes of color,”[xv] Charters remembered. With its larger audience, the recording equipment, several photographers, the fancy chairs, and dramatic lighting, this reading may have been marketed as a repetition of the one at the 6 Gallery, but it was in many ways the very opposite of that humble event.

In addition to the change in venue, the lineup of poets was different. Lamantia was out of town, so the six had become five, but Rexroth was no longer merely the M.C. or “introducer,” as Ginsberg had called him. He was now one of the performing poets and he would read one of his more unusual works. The order of speakers also changed. Whereas Snyder had gone last in October, he was now first on the bill, possibly because he was by far the most confident of them.

For the reading, Snyder had his hair cropped extremely short and wore a dark coat over a sweater. He was only twenty-five but looked even younger. For the first reading, he had dressed in his lumberjack clothes but now he resembled an urban hipster. Sitting next to the smartly dressed McClure and the dorky Ginsberg, drawing casually on his cigarette, he looked more like a rockstar than a poet. (The Beat Museum has a few photos from the event halfway down this post.)

All the poets read different works this time around and Snyder chose “For a Far-Out Friend,” “Song and Dance for a Lecherous Muse,” and the latest version of Part I of Myths & Texts, which he had been working on for several years. After his first poem, he received a big applause and responded by shouting “I suspect dishonesty!” which caused the audience to erupt in laughter. His poems were on serious topics but he infused them with humor and knew how to work a room. Before reading from Myths & Texts, he told the audience, “After I read at the San Francisco Poetry Center, Rexroth said to me, ‘Your animals have got the loosest bowels!’” and yet more laughter filled the hall. Indeed, his poems sometimes referenced feces and Ferlinghetti later termed his style “Bearshit-on-the-trail poetry.”[xvi] It wasn’t only his witty asides that amused his listeners; certain lines in his poems elicited laughter even when he was making a serious point. When talking about deforestation, he tied it to religion and remarked that Christians “would steal Christ from the cross if he wasn’t nailed on.” Occasionally, someone would shout out in response to a line, and the quick-witted poet was able to respond with yet more humor, bringing an interactive, participatory dynamic to the reading.

Whalen followed up with a well-received reading, performing “For K.W. Senex,” “The Martyrdom of Two Pagans,” “Plus Ça Change” (which he called “The More It Changes, the More It’s The Same Thing” perhaps due to his 6 Gallery audience having not fully understood the humor), “Three Variations, All About Love,” a short section of “Sourdough Mountain Lookout,” “Static,” parts of “The Slop Barrel: Slices of the Paideuma for All Sentient Beings,” and “Denunciation, or Unfrock’d Again.” The poems he read were very different from the published versions and he did not always give the title when reading. He read “Denunciation” as though it were a section of “Slop Barrel,” suggesting that at the time these were indeed intended to be one poem. “Sourdough Mountain Lookout” was very much a work in progress, and its composition had been inspired by watching Ginsberg work on “Howl.”

He started nervously and the audience did not seem to understand him at first, with his first poem ending suddenly, leaving the room silent. The second poem also appears to have confused the audience, who responded this time with a hesitant applause. However, “Plus Ça Change / The More It Changes, the More It’s The Same Thing” elicited a lot of wild laughter. Once his audience understood his style and humor, Whalen became a confident reader, deftly able to lead listeners towards important realizations. He also began to throw himself into his performance with the last poem, doing accents, acting out various roles, and varying his reading speed for comic effect, then switching to a deadpan style for certain lines. His jazzy performance of Part III of “Three Variations” was also extremely popular. The audience loved it, with some people crying with laughter, and he ended his reading to a long and rapturous applause.

“It is being debated whether we should have an intermission or keep going,” Rexroth said before pointing out that there was nowhere for the audience to go. Indeed, there probably wasn’t. The “theater” was a converted refrigerated warehouse that had briefly been a gym. There was a lobby of sorts but the theater was quite small and rather makeshift, so likely if there was an intermission the audience would have spilled out onto the street, and someone would have had the unfortunate task of herding dozens of drunk bohemians back inside. Realizing this, Rexroth then introduced Michael McClure, who had read at the Poetry Center the week before. “I understand that he had a sudden burst of creativity of a very high-class nature,” Rexroth told the audience.

McClure stood up from his wooden chair and addressed his audience in a smart grey coat over a plaid shirt. Before he started his reading, he read a letter from Jack Spicer, who was stuck in Boston and begging for help getting back to San Francisco.[10] Spicer had moved to the East Coast in July in an effort to improve his literary prospects, which was more than a little ironic given that the San Francisco Renaissance began just a few months later, but he hated everything about it. He wrote to John Allen Ryan in desperation and Ryan (who had missed the 6 Gallery reading but had now returned from a six-month stay in Mexico) passed the letter to McClure, who read it to the crowd.

When Spicer’s name was read out, there was much cheering. Someone (the voice sounds like Snyder’s) shouted, “Jack Spicer turns tricks on Mars!” This was a reference to Spicer’s obsession with the made-up “Martian” language that he used with his lovers.[xvii] The letter was well-written even though McClure struggled to decipher the handwriting. Clearly the work of a poet, it sounded good when read aloud before an audience, so it was an oddly memorable part of the evening in spite of it being a sincere and desperate cry for help. Spicer said he was “lonely as a kangaroo in an aquarium” and that he “would leave for San Francisco tomorrow if it were not for the horror of unemployment.” He begged for help finding a job and said he would consider “anything from nightwatchman at a museum to towel boy at a Turkish bath.” “San Francisco has a chance to regain its second poet,” he said. Although the letter entertained the crowd, no one helped him and Spicer remained stuck on the East Coast, depressed by his surroundings and resentful that San Francisco’s poetry scene was blossoming in his absence. “I hate this town,” he wrote to Ryan in another letter. “Nobody speaks Martian.”[xviii]

McClure had with him an almost comically large binder full of poetry, from which he selected his readings for the night, apparently unprepared. His choices, however, were quite similar to what he had read in October. He read “Poem,” “Mystery of the Hunt,” “Point Lobos: Animism,” an unnamed poem about whales, and “The Feeling.” After the high-energy performances of Snyder and Whalen, McClure’s reading was conspicuously sedate. He read in a flat tone and the audience was silent throughout, usually unaware when he finished a work, leaving an awkward silence. They only responded with interest when he picked up his large binder and struggled to find a poem. When he selected his fourth poem, he introduced it as “another poem about whales” but did not give it a title. It does not appear in any of his books, either. It is clearly based on the same event that “For the Death of 100 Whales” addressed but it is an entirely different work, repeating the line, “the whales in your chest.” This poem seems to suggest that modern American life was killing whales rather than bullets. They were being killed by retirement funds and creature comforts even if “the army is mowing them down.”

At the end of his performance, there was no applause. Perhaps it was for this reason that in “September Ridge,” Will Petersen wrote that McClure was “almost booed off.”[xix] Certainly, no booing can be heard on the recordings of that night, but it was not a successful performance. Petersen’s poem, rather cryptic, says “Expressionists impatient / wanting wantonness, long before minimalism.”[xx] He seems to be saying McClure was too subtle for them and that they wanted something funny or rude, and indeed the only real snicker came when he said “clitoris,” so Petersen might be right. The audience that night was evidently drunk and tittering, looking for fun and laughter rather than serious contemplation, and before McClure they had gotten a mix of intelligent poetry and silly humor. McClure, however, had only brought the former.

Next, in a big change from the 6 Gallery reading, Allen Ginsberg introduced Kenneth Rexroth. He joked that Rexroth was “a very famous writer of nursery rhymes” and Rexroth drunkenly repeated that idea but then clarified that “actually, these are parodies of nursery rhymes.” At one point during the reading, providing commentary on his own work, he claimed at least part of it was a translation from French, but the origins of the poem are unclear. He started by reading the first three stanzas of his poem, “Mother Goose”:

Do not pick my rosemary.

Do not pick my rue.

I’m saving up my sorrow,

And I have none for you.

After these oddly conventional stanzas, he paused to joke about how unfashionable it was to read “old-fashioned poetry that rhymes.” It was a carefully calculated insertion because the next lines are about a masturbating ogre and women’s urine, all linked together with childish rhymes. The audience was suitably amused. He continued with his poem, sometimes explaining parts between stanzas.

Next, it was Ginsberg’s turn. Rexroth introduced him in his usual joking style: “And now, for better and worse…” but Ginsberg was not in the mood for joking as he planned to begin with “Howl.” The audience had been laughing and goofing around, heckling the speakers in a playful way, but when Ginsberg stood up to read, someone made a noise and the whole crowd laughed, clearly annoying him. He tolerated it for a while but then became audibly irritated and said, “I won’t put up… cut out all the bullshit now.” He told them he wanted to “read without sound effects […] without hip static.” The audience quietened for a while but would punctuate his reading with shouts and laughs, mostly enthusiastic but also distracting and inappropriate. Ann Charters, sitting in the audience, did not care for it either. She recalled being impressed by the poets but “unnerved by the drunken wildness of their friends in the audience.”[xxi]

Ginsberg, who was not drunk but was drinking during his reading, appealed to his listeners by explaining that this was a different sort of poem to the ones that had been read before it. In one recording of the event, it is just possible to catch the following remarks:

The difficulty is to read straightforward through without laugher, y’know, for a moment. The difficulty is to read straightforward through intelligently to arrive at some kind of emotional conclusion with everybody, which I feel pretty strongly having read the poem several times and feeling a certain amount of insincerity in reading it over and over and over again. […] What I’ve done is revise the poem, so I’m reading it in a sense afresh with revisions in it which I’m testing out still […] so in a sense I’m reading you an old poem with revisions. A lot of you have heard a lot of it already.

It is interesting if not wholly surprising that he admits feeling “insincerity in reading it over and over and over again.” Even by February, he had become tired of reading it, for it was a long, emotionally exhausting work. It took a substantial amount of focus and energy and no doubt brought to mind dark moments from his personal life. If he did not invest enough effort and become emotionally involved, then he felt it was a hollow performance that did not do the work justice.

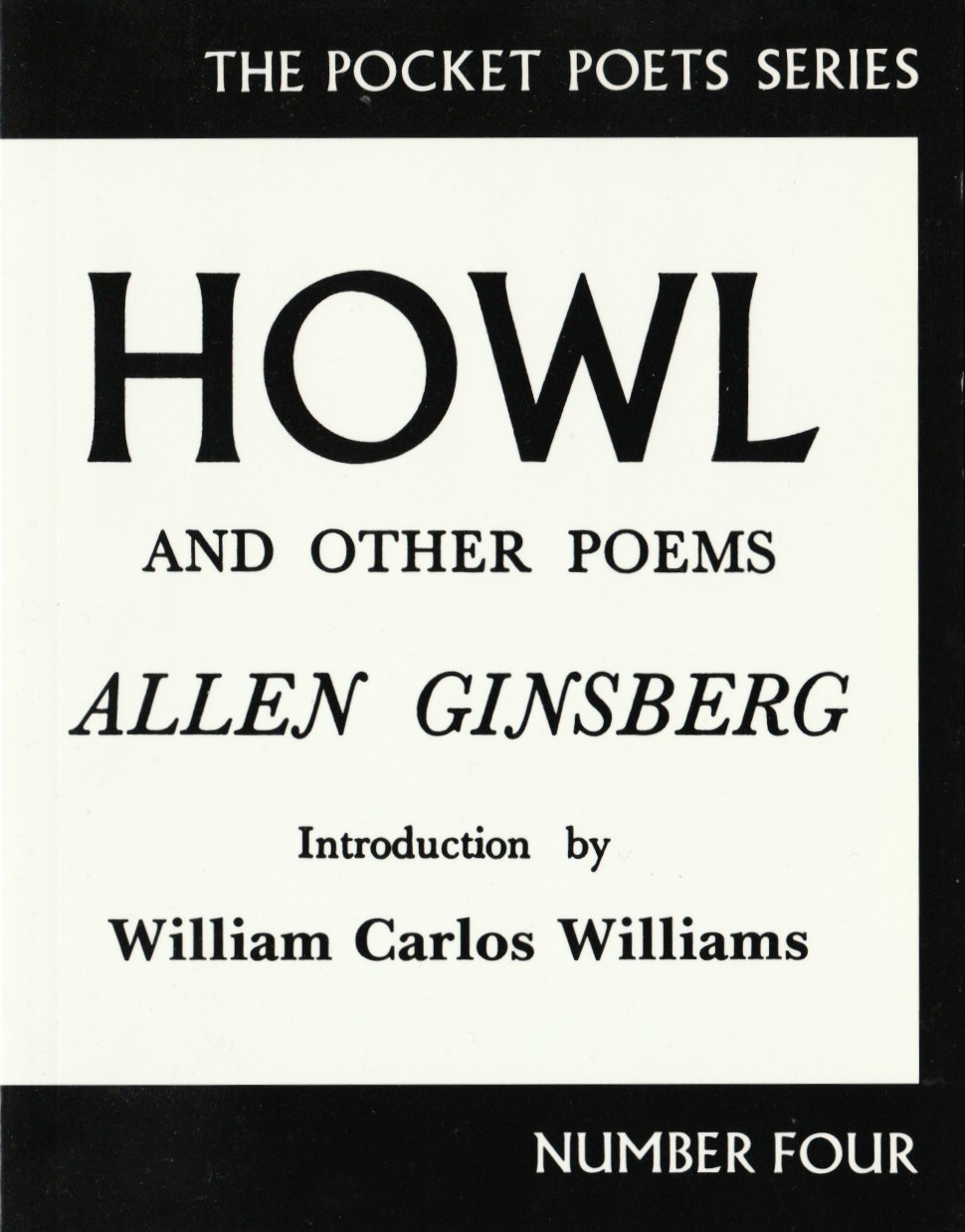

The audience more or less knew what to expect. By now, “Howl” was relatively well known and so was the poet. Rexroth had introduced Ginsberg by saying that he needed no introduction and someone in the audience even asked, “Is this the Ferlinghetti poem?” to which Ginsberg replied, “Yeah. Same poem. Same poem.” By March it was already common knowledge that he had an exciting work that would be published by City Lights, yet he was keen to stress the fact that this was a work-in-progress and that it had changed a great deal, so the audience should not expect exactly the same work he had read at previous events, or for that matter the same one that would later be published.[11]

Photos from the reading show Ginsberg in a dark-colored sports coat over a shirt and tie. His clothes are several sizes too large and his jacket and trousers do not match. He looks rather goofy, especially compared to the painfully hip Snyder and the achingly handsome McClure. Yet in a famous photo of him from that night, his hand is nonchalantly in his pocket and he is confidently and happily addressing his audience. He is beneath stark white lights, a thick pile of papers open in his right hand. He seems very much at ease. It is astonishing that just six months earlier he had given his first ever poetry reading.

This time around, Ginsberg read the whole of “Howl.” It was not exactly the same as the published version, but it was getting closer. He read what was then the in-progress version of the book, which featured a dedicatory page listing his friends’ unpublished books. This included a dedication to Lucian Carr, something that would appear in the first edition but would subsequently be removed due to Carr’s desire for anonymity. The title of Naked Lunch, not published for another three years, got a big laugh.

Once again, he read very slowly, focused on individual words or small groups of words rather than whole lines: “I saw the best minds of my generation… starving… hysterical… naked… dragging themselves through the negro streets… at dawn… looking for an angry fix…” It is extremely slow and the pauses are odd, but they allow his listener the chance to contemplate each line rather than merely consume it. Once again, the poem gave him courage and with each line and with each passing minute that he spoke he grew in volume and power. Within five minutes he was chanting his great poem as though he were delivering a religious message, gesturing and shouting in certain emotional parts. “It was, in a way, sort of scary,”[xxii] Whalen recalled. The audience began to signal its enthusiasm, laughing as most did at the line “who reappeared on the West Coast investigating the FBI.” Sometimes the laughter and applause caused him to stall and pause longer than he wanted, but he continued and gave a fine reading. In total, the first part of his poem took about 20 minutes to read.

After a short pause, he slowly began Part II and then quickly proceeded with a deeply emotional, almost disturbing reading of “Moloch! Moloch!” By now, the audience was silent. There was nothing to laugh at here. They listened intently as Ginsberg delivered his terrifying sermon. They were captivated. A small ripple of applause followed Part II and then he began Part III: “Carl Solomon! I’m with you in Rockland / where you’re madder than I am.” He continued his passionate reading, now thoroughly in control. It was a powerful performance. One biographer recalled the end of “Howl”:

When Ginsberg finished with the last shouts of “Moloch, Moloch” someone backstage began turning the overhead stage lighting on and off, bathing the stage in shades of yellow, red, and blue. The other poets, who were sitting on the stage behind him, stood up and solemnly shook his hand.[xxiii]

In fact, Ginsberg did not finish by shouting “Moloch, Moloch” because this time he read the whole of the poem, ending with Part III, which finishes “in my dreams you walk dripping from a sea-journey on the highway across America in tears to the door of my cottage in the Western night,” receiving a loud applause for his efforts. It was a great success but certainly the audience that night had been primed for Snyder and Whalen. They were drunk and rowdy, looking for something to laugh at rather than the emotionally charged masterpiece Ginsberg had brought. Ginsberg, whilst a gifted reader, lacked the force of personality Snyder had and even the shy Whalen had transformed into an outgoing speaker once he knew the audience understood him. Their playful works entertained the masses more than Ginsberg’s emotional oration.

The same biographer claimed that “the audience jammed into the aisles” and that Kerouac rushed the stage to embrace Ginsberg and his other poet friends, but this too was incorrect.[xxiv] After he finished “Howl,” Ginsberg went on to read several other poems. There was no invasion of the stage. No dramatic lightshow. No wild applause. No audience surging into the aisles. Instead, he finished his first long poem and continued with “Sunflower Sutra,” “A Supermarket in California,” and “America.” He did not, as some have claimed, read “Footnote to Howl.” Again, memory has resulted in a distortion of reality and even though it is minor, mythology has supplanted factual history in spite of the existence of several recordings.

What is most surprising about this reading is that “Howl” was by far the least well received of these four poems. The audience enjoyed it, but they were far more enthusiastic in their responses to the others. Certain lines from “A Supermarket in California” produced big laughs but the highlight of the reading was “America,” which was very different to the version published later that year. Ginsberg started it with a notable lack of enthusiasm, speaking flatly and sounding eager to get through it as quickly as possible, yet again and again the audience reacted to parts they liked and Ginsberg got into the swing of it, feeding off their energy. Lines like “America I used to be a communist when I was a kid I’m not sorry” and “I smoke marijuana every chance I get” received some of the biggest laughs of the night and when he finished the first section of the poem there was nearly thirty seconds of rapturous applause. It took a long time to read because the audience kept laughing and clapping, meaning that once again Ginsberg had to add more pauses than he otherwise would have. The response was so positive, in fact, that Ferlinghetti—who was sitting in the audience—decided the poem had to be included in Howl and Other Poems. Ginsberg was uncertain about “America,” sometimes loving and sometimes hating the poem (an apt feeling given his attitude towards his own country) but Ferlinghetti made various changes to the book against Ginsberg’s will, and his astute judgements helped it to become the success it did. As for “America,” even if Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Corso all felt it was a weak poem, it remains one of his most popular.

When the reading finished, there was of course an afterparty, but Ginsberg did not attend. Unlike in October, he now had a job and needed to get up early. He was rapidly moving towards fame but not quite there yet, so for now he had to slog away in the Greyhound baggage room, writing and performing his poetry only in his spare time.

Soon after the Berkeley reading, Ginsberg explained to his father just how successful it had been:

The reading was pretty great, we had traveling photographers, who appeared on the scene from Vancouver to photograph it, a couple of amateur electronics experts who appeared with tape machines to record,[12] request from State college for a complete recording for the night, requests for copies of the recordings, even finally organizations of bop musicians who want to write music and give big west coast traveling tours of Howl as a sort of Jazz Mass, recorded for a west coast company called Fantasy records that issues a lot of national bop, etc. No kidding. You have no idea what a storm of lunatic-fringe activity I have stirred up.[xxv]

The 6 Gallery had been the first sign of a major poetic movement, but it was the follow-up reading that really grabbed people’s attention and pushed the movement towards a wider audience. In that same letter, Ginsberg said “there appears to be, according to Rexroth, a semi major renaissance around the west coast due to Jack and my presence—and Rexroth’s wife said he’d been waiting all his life hoping for a situation like this to develop.”[xxvi] The use of the word “renaissance” was prophetic for that is precisely what the local poetry scene would become known as—the San Francisco Renaissance. Many disliked or disagreed with the name. Duncan complained that “[t]he term […] shows that someone didn’t know what a renaissance was at all. What did it mean? That we revived the Yukon poets or something?”[xxvii] Ann Charters paraphrased a great many people in noting that “[p]oetry had no need to be reborn in San Francisco since it had always been alive there.”[xxviii] Later, Ginsberg would push for the term “revolution” rather than “renaissance” but whatever the terminology, there can be little arguing with the fact that there was a vast enlargement of interest in poetry at this time and that it stemmed to no small degree from the poetic and promotional efforts of Ginsberg and his Beat peers.

The 6 Gallery reading is often seen as the birth of this movement and a pivotal—perhaps even the most important—movement in the creation of the Beat Generation. This is true to an extent but it did not happen in isolation. A great many events before and after, including this reading, helped make literary history. It is quite possible that without this “repeat performance,” the excitement might have faded away or stayed within the Bay Area, but soon after it would spread across the country. Events like this filled Ginsberg in particular with confidence and gave him the energy to launch the most effective literary publicity campaign of his era. It inspired others and gave rise to a culture of poetry readings that was remarked upon in the national press, helping bring San Francisco a well-earned reputation for contemporary poetry and making it the home of the counterculture. It is for that reason that these readings must not remain as myth or overlooked as mere footnotes.

Reasons for Errors

The first book that really dealt with this event was written in the early seventies by a Beat biographer who actually attended this reading. Alas, without access to the digitized documents we have today, that account was based largely on memory. This was a decade and a half later, and of course memories can hardly be trusted at that point. Could you remember the specifics of a poetry reading that you attended fifteen years ago, particularly one you attended in the middle of a boozy evening? These memories resulted in a colourful and interesting but wholly inaccurate account. Mistakes that were made include: the date, details of the venue, descriptions of the art on display, the order of poems read, the clothes the poets wore, the poets that read, the poems read, and how the event ended. It was also the first book to use the phrase “repeat performance,” which as we saw above is an understandable if somewhat inaccurate term. That same book mixed together the texts for the postcards sent out to publicise the 6 Gallery and Town Hall readings, creating a made-up text that was given as the postcard for the first reading and even today is typically used even though the real one emerged—thanks to the same biographer—in the mid-eighties. Unfortunately, these mistakes have been repeated due to the importance of that landmark publication. It certainly deserves respect for being a pioneering book but we ought to do better than merely repeat its claims, particularly now that it is possible to find more reliable documents that allow for a far more accurate picture.

Footnotes

[1] I found two dozen texts that used “repeat performance” to describe this event and then stopped counting. The first of these was Kerouac: A Biography.

[2] No photos, audio recordings, or videos have been found and likely none were made. Some suggest it may have been photographed and Gary Snyder said in late 1955 that there was a tape of Ginsberg reading “Howl” but it’s not clear what reading that comes from and it is probably lost to time anyway.

[3] This is extensively discussed in my forthcoming book on the 6 Gallery. Almost everyone on stage later tried to take credit but the evidence is clear that it was almost all down to Ginsberg. Snyder was most adamant that he arranged the event with Ginsberg, stating this a number of times, but he was mistaken and confused the two readings.

[4] There were, at various points in the city’s history, a number of other “town halls,” but these seldom stayed in the same place and none of them were the “Town Hall Theater” where our reading took place.

[5] Snyder had recently moved from Berkeley, where he was living when Ginsberg first met him in September 1955, to Mill Valley in Marin Country, where he now stayed with Locke McCorkle. He had finished his studies at U.C. Berkeley and was preparing for his trip to Japan in May.

[6] One of these—recorded on February 14—was recorded and that tape was recently discovered. It is the earliest known audio recording of Allen Ginsberg although Gary Snyder, in private correspondence from late 1955, noted that there had been a tape of Ginsberg presumably made in October or November.

[7] Primarily straight, Orlovsky often dated or slept with women and Ginsberg was fine with this.

[8] LaVigne certainly did draw Ginsberg and Orlovsky nude together on at least a few occasions (see Straight Hearts’ Delight, for example), so perhaps Charters has mixed up her memories of this event with LaVigne illustrations that she saw elsewhere.

[9] Rexroth’s relationship with the Beats is worthy of a book-length discussion. He had already decided he hated Kerouac but this hatred would massively increase in the coming few months. He may have felt some antipathy towards Ginsberg and certainly despised him later. He would remain good friends with Snyder and Lamantia although he could be a little bitchy even about them, and he was close to Ferlinghetti throughout his life even if he did occasionally talk badly about him behind his back. “He could be very cruel to people,” Snyder explained, and this is an understatement from a person who tolerated him more than most.

[10] Many Beat histories incorrectly state this occurred at the 6 Gallery reading.

[11] There is no way to know for sure what version of “Howl” Ginsberg read at the 6 Gallery but, contrary to most accounts—including Ginsberg’s own memory—he does seem from what people said in the following days to have read more than just Part I. Importantly, whatever he read in early October was very different to the version he had in late March.

[12] Ginsberg’s portion of the reading was released in Canada by Pinewood Soundtracks in July 1956. It was credited to “Allen Ginsburg.” There were actually several people in the audience recording the performance, including Walter Lehrman. Lehrman had been at the 6 Gallery reading and soon after bought a camera. Over the coming months, he took numerous photos of Ginsberg, Snyder, and the other Beat poets, including one of Ginsberg reading at the Poetry Center in November 1955, which is almost certainly the first photo of Ginsberg reading his poem.

Endnotes

[i] Jack Goodwin to John Allen Ryan, December 3, 1955

[ii] Berkeley Gazette, April 24, 1956, p.11

[iii] Oakland Times, August 21, 1955, p.67

[iv] Stockton Evening and Sunday Record, December 16, 1957, p.18

[v] Oakland Tribune, December 28, 1958, p.80

[vi] The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, p.3

[vii] Brother-Souls, p.249

[viii] Brother-Souls, p.249

[ix] “Philip Whalen talks to Steve Silberman”

[x] “Flashback: Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Strange New Cottage in Berkeley’,” by Tom Dalzell

[xi] Memory Babe, p.569

[xii] Gary Snyder: Dimensions of a Life, p.76

[xiii] The audio recordings of all poets except Ginsberg are on a digitized tape hosted at Stanford. URL: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/fg667wg6291 Meanwhile, Ginsberg’s section is hosted separately: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/wz608kc4019 These are erroneously listed as having been recorded at the 6 Gallery.

[xiv] Kerouac: A Biography, p.271

[xv] Kerouac: A Biography, p.271

[xvi] “Interview with Gary Snyder,” by John Suiter, December 6, 2000

[xvii] Poet Be Like God, p.57

[xviii] Poet Be Like God, p.63

[xix] Gary Snyder: Dimensions of a Life, p.76

[xx] Gary Snyder: Dimensions of a Life, p.76

[xxi] Women of the Beat Generation, p.336

[xxii] “Philip Whalen talks to Steve Silberman”

[xxiii] Brother-Souls, p.249

[xxiv] Kerouac: A Biography, p.255-256

[xxv] The Letters of Allen Ginsberg, p.129

[xxvi] The Letters of Allen Ginsberg, p.128

[xxvii] Poet Be Like God, p.78

[xxviii] Kerouac: A Biography, p.249

Note: This essay was lightly edited about 24 hours after first being posted, due to a mistake I had made. I said Jack Kerouac was in the audience but he was not present that night, as he was on the other side of the country. Thanks to Ann Charters for pointing out my error.