Allen Ginsberg in Southeast Asia

An in-depth exploration of Ginsberg’s 1963 trip through Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia.

Introduction

On March 23, 1961, Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky set off by ship from New York City, arriving several days later in Le Harve, France. It was the first stage of a more than two-year circumnavigation that would take them through France and Morrocco, Greece and Israel, Kenya and India, and many more countries before arriving back in the United States in August 1963. For Ginsberg, the trip was of almost indescribable importance. He changed so astoundingly as a poet and as a human being during his restless wandering that the man who returned to America was barely recognisable. By then, he had become the Allen Ginsberg that would be synonymous with the hippie movement—the long-haired, bearded, beaded, pyjama-clad, cymbal-clanging, anti-war activist so frequently found at demonstrations and happenings, chanting mantras and bellowing OMMMMMM to enthusiastic crowds.

The trip has been relatively well documented, particularly the period during which he and Orlovsky were in India. Whole books have been written about Ginsberg in India, as well as a short documentary. Even his Indian journals have been published. Yet, as is so often the case, there is a bit of a gap in the story. In books about Ginsberg’s life, we see him in Morocco and Europe, then the Middle East, then India, and finally Japan. It’s true that the accounts of countries visited before and after India feel almost like a prologue and epilogue, but they are detailed to some extent, his adventures there recounted and his opinions shared. That scholars and biographers focus on India is entirely understandable, for it is obvious that it was the most significant of all his journeys, causing him to undergo radical changes in personality, politics, and poetics.

In the poem, “The Change,” written in July 1963, and in various comments made in letters later that same year, Ginsberg explains that his travels in India had taught him so much that he could not process all he had learned until many weeks after leaving the country. After India, he travelled quickly through Southeast Asia, then spent a month meditating with Gary Snyder and Joanne Kyger in Kyoto, Japan, before finally coming to understand everything as he sat on a train back to Tokyo. In the months after returning to North America, he ran around “in a happy rapture,” kissing people and expressing his love for all the world.

Considering all that, it is quite reasonable that books about Ginsberg skip over his time in Southeast Asia—a mere twelve days between the India trip that taught him everything and the Japan trip that allowed him to understand those lessons. Compared to those trips, the Southeast Asian journey was of little importance. Biographers tend to note that he flew to Japan via Bangkok, Saigon, and Angkor Wat, but they say little about what he did in these places, and several have named the wrong cities and countries. Reading these accounts, one gets the feeling Southeast Asia was merely a layover, a place to kill time between flights.

It is not only biographers and scholars who have overlooked Ginsberg’s sojourn in Southeast Asia. Indeed, the poet himself hardly wrote anything whilst there and took no photos at all. His journals contained few notes, almost no letters from this period were saved, and he moved from one place to the next with uncharacteristic rapidity. The man who delighted in spending weeks, months, and sometimes years exploring foreign cultures spent less than two weeks in this region, visiting just three countries before leaving. In these countries, he only visited the primary tourist spots, foregoing his usual cultural explorations.

Looking back, he spoke often of India, a little of Japan, and to varying degrees about the other countries he’d seen on that long round-the-world voyage, but he seldom mentioned any of the Southeast Asian countries he’d passed through except to talk about Vietnam as it concerned geopolitics. It didn’t seem to fit into his biography, his self-mythology, his poetic development. Even by March 1964, Ginsberg was claiming that “The Change” had been the only poem he’d written “in years,” evidently forgetting the numerous minor and experimental works he’d produced on his travels, as well as the long poem, “Ankor Wat,” written in Cambodia just a month prior to “The Change.” In fact, his Collected Poems include no fewer than three works from the brief time he spent in Southeast Asia and many more from India.

I must say that I found this not only unusual but in fact I was almost offended by such a conspicuous omission. I have spent much of my life living in and travelling around Southeast Asia and it’s hard to see what Ginsberg wouldn’t have liked here. When doing research for my 2019 book, World Citizen: Allen Ginsberg as Traveller, I was shocked by just how little evidence there was that he’d even passed through this part of the world. A few years later, when asked to talk about Ginsberg in Siem Reap, Cambodia, I tried to look further into his time there but still found little to go on. In his archives, there were only a scattering of nearly illegible notes, a couple of phone numbers, a few doodles. Had it all meant so little to him? Where were the long, vivid descriptions of people and places? Where were the spontaneous poems written in cafés and temples? His journals and notebooks from this period were almost empty. Whole days went by without a word written and what little he did write was generally not connected with his present travels.

Knowing how Ginsberg travelled and what he liked to see, it just didn’t make sense to me that he would’ve come to this part of the world and left without recording it or planning a return trip when he had more time. Southeast Asia is a stunningly beautiful place, brimming with culture old and new. It is bright and exotic, yet ancient and challenging. He had loved Mexico and Morrocco and India… so why not Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia? I knew, for example, that he yearned to see the temples of Indonesia, and of course he’d long wanted to see Angkor Wat, and yet he had swept through only three cities in a period of about 12 days, hardly leaving a trace.

Why was that? Did he simply not enjoy his time here?

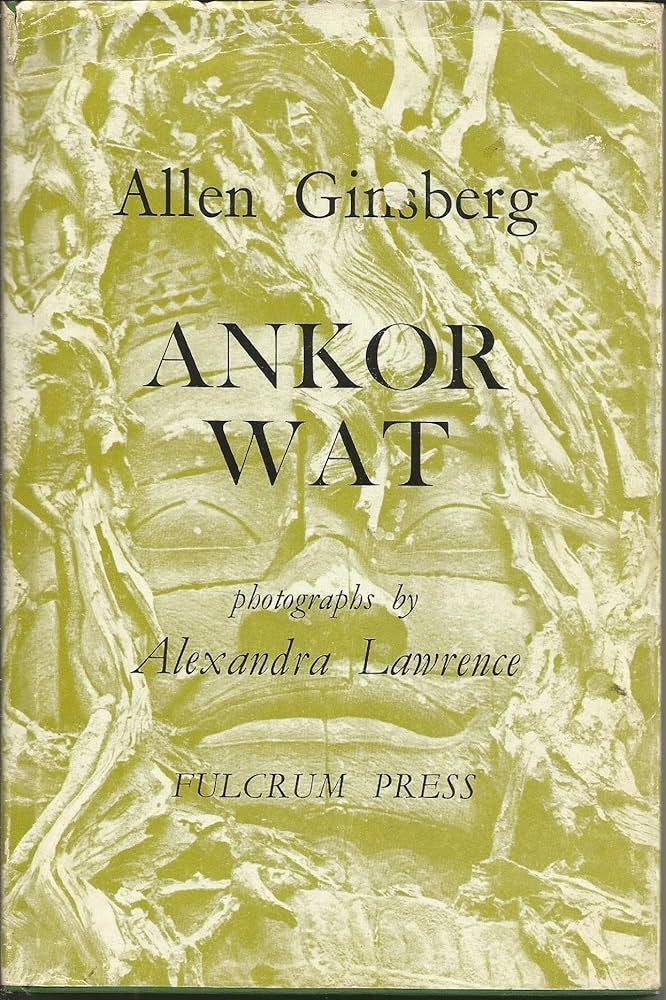

Clearly, the temples of Angkor Wat left an impression on him. After all, he wrote a long poem about them that was later published as a book (Ankor Wat, Fulcrum Press: 1968). The poem, though, is more about the poet than the temples and more about geopolitics, too. He even spells the name wrongly. He was bad at spelling and often made up odd names for places based upon what he heard local people say, but for someone so meticulous about cultural and religious history, with access to an array of books—both scholarly and otherwise—it’s strange to me that he got this one wrong and that he let his poem be published in a variety of places without correcting it. Again, it suggests that the trip just wasn’t that important to him.

After some digging about in the archives, I was finally able to piece together some information about Ginsberg’s time here. I was able to establish a chronology of his travels, to locate many of the places he visited, and to identify some of the people he met with. From what I found, it appeared that he was impressed by the region. The scenery, the food, the drugs, the young male prostitutes, the intellectual companions, the history, the culture… From what few notes he made, it seems that he found Southeast Asia stimulating and enjoyable.

So, again, why did he make almost no effort to document it?

It is quite possible that he was simply suffering from an intense traveller’s fatigue. By the time he arrived in Bangkok, the first stop on his flying visit, he had been on the road for twenty-six months. It had been rewarding but exhausting. He had been perpetually broke and often overwhelmed by the world around him. In the previous months, his health was poor and his relationship with Peter Orlovsky had deteriorated badly, too. He was disturbed by the military build-up in Vietnam and the possibility of nuclear apocalypse. It is likely he simply wanted to get to Japan and relax for a month in relative peace and quiet. Perhaps he needed more modernity than Southeast Asia could offer back then. Perhaps this part of the world was too similar to the one he had just left. It is something Snyder—who had travelled with Ginsberg near the beginning of his India trip—seemed to have recognised. In April, he wrote Ginsberg:

Why not leave serious sightseeing in Saigon, etc. til later boat trip at leisure and come straight on to Japan this time?

Ginsberg replied:

Despite your good advice I’m going to try to get to Angkor Wat, since I can fly there free. It may take me two weeks or more tho. Anyway, I hope to arrive in Japan by June 15 more/less.

Ginsberg was determined to see Angkor Wat but there was also Saigon, where—in spite of his anxiety—he knew he would witness first-hand the horrors of an escalating war. For Ginsberg, travel was not always about fun. Sometimes it was a matter of educating himself through exposure to the more unpleasant parts of the human experience.

And so he set off for Japan via Southeast Asia, ultimately spending twelve days split between Bangkok, Saigon, and Siem Reap. What little he wrote here tended towards the personal and the political rather than observations of his surroundings. He was clearly in a sort of daze, struggling to process the lessons he'd learned in the slums of India amidst his proximity to the paranoia and destruction ramping up in Vietnam.

But that is not to say that he stayed in his hotel rooms and shut himself away from the world. He certainly did not document this part of his trip as he had done the rest of it, but when we dig deep enough the proof is there that Ginsberg made the most of his time here. He played the role of tourist and traveller, even if only briefly. He ate and fucked, met with poets and journalists, and attempted in a rather short period of time to learn about the culture, both historical and contemporary, of this most vibrant region. It is a shame he did not write more or save more of what he did write, but it is a relief to realise that there was more to this trip than the one famous poem that emerged.

I wrote this essay because I felt that Allen Ginsberg’s time in Southeast Asia did not deserve to be a piddling footnote in his biography, a tiny side-trip of little consequence amidst greater journeys and events. Or maybe I did it selfishly, feeling aggrieved that a part of the world so close to my own heart had been so easily overlooked… Whatever the reason, the research led me to various facts that have never been included in books about the poet and which add to our understanding of him at that point in his life. It was enough to fill this modest essay, which attempts to explain where Allen Ginsberg went and what he did and wrote and thought in these places. There is much that remains a mystery, but therein lies the magic.

Chronology

May 27 – Ginsberg arrives in Bangkok, Thailand

May 31 – Ginsberg leaves Bangkok and arrives in Saigon, South Vietnam

June 5 – The New York Times publishes an article about Ginsberg in Saigon

June 7 – Ginsberg flies from Saigon to Siem Reap, Cambodia

June 10 – Ginsberg writes “Ankor Wat” poem

June 11 – Ginsberg flies to Tokyo, Japan

June 12 – Ginsberg takes the train to Kyoto

July 18 – On the train from Kyoto to Tokyo, he writes “The Change”

July 21 – Ginsberg attends Vancouver Poetry Conference

Thailand

Allen Ginsberg arrived in Bangkok, Thailand, on May 27, 1963. He had been travelling for more than two years, with fifteen months of that time spent in India. Although his time in India had been extremely valuable and for the most part enjoyable, the last month was emotionally challenging. During these final weeks, his relationship with Orlovsky—which had always been tumultuous—became more strained than usual. Peter was “unwelcoming & silent” during this period and one night he took morphine and told Allen that he was “washed up” as a poet and that he had “sold out” by agreeing to fly to Vancouver to teach a three-week course,* which Peter viewed as breaking a vow Allen had made to never read poetry for money. Allen was insulted but he partially agreed with Peter. Depressed, he took a train to Calcutta alone, where he wrote a poem called “Last Night in Calcutta” that captures his mood during the final days. He was lonely, melancholy, and in a degree of pain from kidney problems. Despite his love for the country, he was eager to leave but saw “[n]o escape but thru Bangkok and New York death.”

*There is some debate over whether it was a course or a conference. In any case, there are hours of recordings here. An amusing sidenote is that the University of British Columbia him listed as “Dr. A. Ginsberg” on financial records.

In 1963, Thailand and its capital of Bangkok were not the tourist destinations they are today, with tens of millions of visitors taking advantage of an abundance of cheap flights and a well-developed tourist infrastructure comprised of boats and buses ferrying visitors between beach resorts. Back then, the region was looking decidedly unstable, with the Vietnam War just beginning. Over the previous two years, the U.S. military had become involved there and the situation was escalating quickly. Indeed, the situation was worsening by the day, and just three weeks before he arrived, the Buddhist uprising began with the murder of nine Buddhist protesters by South Vietnamese police. Ginsberg, always politically involved, had been keenly aware of such developments, having read about them in newspapers and Time magazine.

It was a year before the Gulf of Tonkin incident that would officially enter the U.S. into the war, and long before the U.S. would begin bombing Cambodia and Laos, yet already it had begun to use Thailand as a launching point for attacks on North Vietnam. It did so through the establishment of an air force base at Don Muang on the outskirts of the capital. Before hippie backpackers and later generations of bedraggled wanderers, the farang populating the bars and brothels of Bangkok were primarily U.S. military personnel. One can only wonder what they made of the bearded Beat poet in their midst. They certainly had some common ground, for after India Ginsberg was looking for a few days of hedonistic exploits.

All through his India travels, Ginsberg had been celibate and had lived as a vegetarian, but these habits were broken upon arriving in Bangkok. In his journal from May 28, he called Bangkok “a fleshy town, much meat to munch [including] Sukyaki (sic) Chinese pork.” To Peter, he wrote that he was “gorging [him]self on duck and pork” as well as dirt-cheap bowls of shrimp-pork wonton soup. Almost everywhere he travelled, Allen frequented the local Chinese restaurants.

Pork was not the only meat on the menu. “There’s an endless supply of young (Chinese) boys** (in shorts) for boxing for fucking,” he scribbled in another notebook. It appears from his minimal note-keeping that he engaged their services from the first night he arrived in the city. He could feel “the ghost sex rising in [his] loins,” he wrote in reference to the “yellow skin smoth (sic) & hairless” men he encountered. In a letter to Orlovsky, Ginsberg spoke more of these “boys”:

plenty of 19 yr old Chinese boys here—They picked me up & two different times came to hotel—cost 1 or 2 dollars—young hairless skin […] Only trouble is they stick to me like adhesive tape afterwards

**It’s important to note that when Ginsberg said “boys,” he was talking about young adults. More on that unpleasant topic here.

During his few days in Bangkok, Ginsberg stayed at the Silom Thai Hotel, where he had a rather uninspiring room, dimly lit and decorated with brown wallpaper. Outside, in the heart of the city, the daytime was lit by azure skies and the nighttime was a hazy neon glow, but inside his room it was so dark he could hardly read or write. However, after his long period of celibacy, he was more interested in sex than reading and writing and the Silom area of Bangkok—where his hotel was located—had a vibrant gay scene and no shortage of male prostitutes.

His impressions of Thailand are mostly confined to a single poem-journal entry, which is only about 500 words. This is strange, for he appears to have been enamoured of the city, particularly its colours and comparative modernity:

Chinese meats red hanging in Shops – Grillwork & old wood – the river & Dawn Temple bordered by palmtrees, shanties, rowboats – Downtown money changers – King Rama VI Statue, the pedestal at night a park circle of grass, music piped thru to moderne rock & roll & boys lounging on grass or the steps of the Statue, in blue pants & light-weight neat shirts, effeminate or Chinese modern faced in short haircuts black locks & jeans…

It is a characteristic rush of imagery, a noting of sights and sounds in sketch form, but it is all described fleetingly. No single scene or experience is given much space in his notebooks. That is likely because he was rushing around, guidebook in hand, attempting to see as much as possible in the few days he had there. It appears he did most of his sightseeing on May 27 and 28 and then merely noted the highlights at the end of that second day. He writes of “pavilions & sloped azure roofs of Palace Chapels—stone Chinese sages with flowing beards and round ball pop-eyes standing guard at the gates—giant enameled statues—mosaic of old tea cups their eyes.” This is almost certainly the Grand Palace, which indeed is guarded by Chinese-style statues.

He speaks of a “tacky Castle & Church” and goes on to discuss “The Siamese Dancers in de luxe little theater” as he watches them perform when he is high on what seems to be morphine. It seems he had been roped into visiting a rather hollow and unconvincing cultural display put on for tourists—something that remains common sixty years later. He is also taken to a boxing match (presumably Muay Thai, the national sport), where he describes the colourfully dressed young fighters kicking each other on the chin and in the stomach and “scampering around ring surrounded by front seat white haired tourist.” He sees a man resembling “Cezanne’s dollike card player […] snapping pictures & lurching in his seat” but sadly Ginsberg did not take a single photo whilst in Southeast Asia. Asked about this by a Cambodian journalist, Peter Hale, who manages Ginsberg’s estate, speculated that he had run out of film during his two-year voyage, which is quite likely.

His notebook very briefly mentions a long walk through the city, seeing the Democracy Monument, built in 1939. He says, though, that it is an oddly militaristic city. There are clubs and seedy parts of parks where he can score for sex and drugs, but somehow it appears oppressive. Men in uniform abound and the traffic, too, is chaotic. Still, though, his tone is generally enthusiastic and he appears taken by the bright, pulsating, culturally rich capital. Elsewhere, he comments upon people being generally quite friendly, remarking upon Bangkok as being like Tangiers except “more polite.”

In his notes, Ginsberg mentions two other attractions in Bangkok: “a huge golden Budaha (sic) reclining in temple big as ship” and the “National Museum Sukothai (sic) Style.” The former is Wat Pho, also known as the Temple of the Reclining Buddha, and the latter is Ramkhamhaeng National Museum, which features Sukhothai-style artworks. Oddly, there is nothing more about either of these in his journals, nor does he reflect on them in any of his later writings. He refers briefly to the museum as “very great,” but that is about as descriptive as it gets.

In another notebook, in which he mostly kept contact information, currency exchange rates, and other important details and ideas, he wrote a 50-word sketch of a morning scene in Bangkok that on the following page he turned into a poem. Quickly written, it is nearly illegible and has never been published. In it, he describes a peaceful morning near a lake in a park, “the rich Bankok / pavilion red blue neon / reflections softly / like the music / shimmering.” Piano music and even “the purr of motorcycle taxis” float “into the universe of Ear.” This was likely Lumphini Park, located not far from his hotel.

In the same small notebook, he also noted the name Sulak Sivaraksa, a lecturer in the social sciences department of Chulalongkorn University. This institute was about a kilometre north of his hotel. Sivaraksa was a Buddhist activist and editor of Social Science Review and he lectured at Chulalongkorn. At some point during his brief stay in Bangkok, Ginsberg met Sivaraksa, who took Allen to meet a noted Thai poet, Angkarn Kallayanapong, whose name (or at least part of it) Ginsberg had also written down in advance of his trip. Allen referred to him as “a poet, young kid” and called him a “Thai-style classical painter.”

During their meeting, the twenty-five-year-old Angkarn read several poems for Ginsberg, which Sivaraksa translated on the spot. Ginsberg wrote down and modified one of them, which exists in his archives as “Translation of Bankok (sic) Poet” alongside Ginsberg’s attempts to capture the poem’s intonations when read aloud in Thai. Several of these were published in a book about Angkarn, Teardrops of Time: Buddhist Aesthetics in the Poetry of Angkarn Kallayanapong, by Arnika Fuhrmann, including a poem Ginsberg and Sivaraksa translated some years later. (Read more about that at the Ginsberg estate website.)

Ginsberg mentioned in a letter that the three men drove “all around banana palm canal suburbs” but offered no more details. One wonders what else these men talked about during their brief time together. Perhaps they discussed their mutual acquaintance, the Dalai Lama. Did Sivaraksa teach Ginsberg about Buddhism or activism? Undoubtedly, they must have discussed poetics, but what else? Sivaraksa recalled a half-century later some degree of enthusiasm for the famous American poet who had visited him. He recalled having been impressed that Ginsberg had written for Evergreen Review, which Sivaraksa considered the best of American literary journals.

There is nothing in Ginsberg’s journals about his meetings with Angkarn and Sivaraksa and he only briefly mentioned it in one short letter, written the night before leaving Thailand. By all accounts, he enjoyed his time in the country and found the intellectual company stimulating. He appears to have enjoyed the food and sex and drugs and culture and architecture… yet it all merited little more than a 500-word journal entry and a 50-word poem. There are no sketches, no long, vivid accounts of what he saw and who he spoke with. He told Orlovsky that it was a shame he could not see more of the country, for he could tell it would be “lovely,” but still his enthusiasm was limited. A short letter written at the end of the trip recounts a positive, enjoyable trip, saying the place was “sorta like Tanger but more polite.” It is telling, though, that he summarised his trip by saying that Bangkok “was fine.” He even recorded the whole thing as taking place in “Bankok” rather than “Bangkok.” This may seem trivial, but for me it is an indication that the trip was so fleeting, so meaningless, that he barely noted the name of the city he had visited. Even so, he did note in that same letter that he regretted he “could not go inland,” suggesting at least some desire to have prolonged his trip and seen more of that fascinating and beautiful country.

One is tempted to speculate that he was simply too busy to write but a great many pages of his journal from these few days are taken up with dream records. These are dreams about T.S. Eliot, Mark van Doren, and Columbia University, though; not Bangkok. The final dream description is fairly typical at first—old faces and places blending over time—but then he has a sort of epiphany. In his dream he has a dream and a message comes from this second dream layer “warning not to believe in Poetry.” What follows is a long poem about the possibilities inherent in dreams. It is stream-of-consciousness, one idea merging linguistically into another, past into present, self into universe. At a certain point, it is clear Ginsberg is no longer in Bangkok. He has flown to Saigon and is completing the poem at night on a small street watching taxis go by. (This confusing transition possibly stems from the fact that he departed at about 6am.)

Saigon

Ginsberg’s circumnavigation had been disorganised and often spontaneous, the poet’s perilous finances and the politics of the day often causing plans to go awry. Even so, he researched each destination, reading books and asking the people he met what he should see and who he should meet. He travelled laden with books and pages and pages filled with contact information. When it came to Asia, he put a great deal of stock in the advice of old friend Gary Snyder, who in 1962 advised Allen about visiting Saigon:

Saigon Museum is quite good: Cham, Khmer, Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetan artifacts. The Mekong Restaurant, straight on the road to town about 2½ blocks after you cross the bridge on the way to the center of town from the ship, is good food not expensive. See the gibbons at the zoo.

But Saigon had been a different place only a year before. The country had only a few years of relative peace between the expulsion of the French and before the emergence of a civil war that would later entangle the Americans, becoming known there as the American War and in the West as the Vietnam War.

Ginsberg was of course well aware of what was happening there, having kept up to date with the news whilst living in India. He knew that his trip to Vietnam would not be one of tourist merriment, nor of hedonism and culture, as was the case in Bangkok. Snyder may have depicted a charming old city filled with history, but in Ginsberg’s mind he was headed to the peripheries of a warzone, a place of rapidly escalating tension, where bombs and bullets could strike at any moment. Despite his anxieties, however, he was keen to learn and perhaps even to influence the situation. He was, after all, a famous poet. One of his notebooks contained a wide array of potential contacts, including the U.S. embassy and the head of the United States Information Service, and here he stated his intention to find and contact representatives of Time, Newsweek, the New York Times, U.P.I., and the A.P. He also made notes to find answers to the following questions:

Are there any intellectual groups and cafés?

Are there any poets?

Can connect me with Buddhist leaders?

Another note shows his interest in finding an “opposition leader” to speak with. He was largely successful in these goals, as we shall see. It appears that most of Ginsberg’s time in Saigon was spent with the foreign press and he was even granted an extensive interview with a U.S.I.S. officer, who was oddly candid. Ginsberg scribbled eleven pages of notes from their discussion. The officer told him quite frankly that the U.S. was trying to control the South Vietnamese government but that “the real art is in trying to get them to do what we want them to do without appearing to do it.” One of the last quotes is, “We have reached this point with Diem—our policy is to support this govt all the way.” Ngô Đình Diệm, the South Vietnamese president, was assassinated just five months later, possibly with the complicity of the U.S. government.

Over the coming decades, Ginsberg said relatively little about his time in Southeast Asia except to tell a number of interviewers that Saigon had been an eye-opening experience. The following quotation, from 1978, is representative of several others he made:

I went through Saigon in the early 1960s, in 1962 (sic), and I got a good look and saw David Halberstam, met a lot of the reporters there, and realised that what was being sprayed out in on TV across America was totally different from what those reporters thought right on the scene, that they knew that it was a loser – a moral loser and a physical loser all along. But my father, who was living in Paterson, New Jersey in 1965, still thought that the Vietnamese wanted us there to protect them from the Communists – which was a big mistake, because they didn’t want us there at all.

Naturally, he did not want to spend all of his time in Saigon in the company of Americans and reading what he perceived to be American propaganda. His little notebook also includes the names of Vũ Hoàng Chương and several other Vietnamese poets. He noted a book he intended to find, published in the Philippines but written by a South Vietnamese politician, Nguyen Thai, called Is South Vietnam Viable? However, there is no indication of whether he met with these people or read their work for he wrote little about his time there. He also paraphrased the “Five Buddhist Demands” of Thích Trí Quang, president of Vietnam’s Buddhist Association, which had been published on May 10, several weeks prior to Ginsberg arriving in the country.

Again, Ginsberg wrote little about his visit. On the first night, he wrote a poem called “Understand That This is a Dream.” It seems to have been written late at night upon waking and it deals with his inner confusion over aging and his relationship with Orlovsky rather than his surroundings, although Bangkok, Saigon, and Angkor Wat are mentioned. The poem implies tiredness and aging and a great deal of uncertainty. Indeed, these seem to be problems that held him back from making the most of his time in the region. The handful of references to his surroundings are mundane: “Motorcycle rickshaws / parting lamp shine / little taxis / horses hoofs / on this Saigon midnight street.”

His journal likewise includes several short dream notations that have no obvious connection to his present location, but there is nothing about his activities in Saigon. Following the entry for June 3, he wrote “Many other sections I go back sleep” as though he just could not be bothered writing more, and perhaps this persistent fatigue—the result of too much travel and too much knowledge gained—is why he wrote little and did little.

Ginsberg was offered the chance to fly out towards the battlefields on a helicopter, but he declined. He was terrified of the prospect. This whole dilemma, however, occupied only a single paragraph in his journal:

Am I coward? Nervous stomach in Saigon not wanting to go to helicopter battlefields in rice paddies & watch Chinese bodies be blown apart?

It is the first and last acknowledgement in his journals that he is in a country at war, which is quite strange given that he was soon to become a pre-eminent anti-war activist and had been tracking with dismay his own nation’s military buildup in the region. But perhaps it was just too depressing to write about. To Snyder, he recalled:

Horrendous days talking to correspondents of U.S. network at Saigon—weird politics, I almost went helicopter to Mekong Delta and said ugh! But I saw Buddhist priests who were on hunger strike against government and U.S. giving half billion $ yearly police state.

To Orlovsky, who was still in India, he wrote:

EEEK – it’s like walking around in a mescaline nightmare – I can arrange to fly inland and see “model hamlets” – battles, but decided no and am scairt… The war is a fabulous anxiety bringdown. It’s awful.

Although he felt cowardly, Ginsberg did not merely stay shut away in his hotel room. He went out exploring, meeting people and seeing what he could. Travel afforded him the anonymity he lacked in the United States, where he was already something of a celebrity. He had freedom also from the media and from requests to read his work or talk with students. For two years, he had been out of the limelight, only occasionally chased down by journalists. Readers back home might have wondered what happened to the scraggly Beat poet who had hardly been out of the headlines since 1956. Was the beatnik fad dead? Was the author of “Howl” old news? On June 5, the New York Times ran a short article entitled, “Buddhists Find a Beatnik Spy.” It began:

The Buddhists, who are in conflict with the South Vietnamese Government, asserted today that they believed the Americans had sent a “spy to look at us.”

For context, Vietnam’s Buddhist population was at this point rising up against the South Vietnamese government, which was being propped up by the United States. According to the Times article, the Buddhists were approached by a strange-looking American man, whom they took for a spy. A spokesman for the Buddhists allegedly told a group of American reporters, “he was tall and had a very long beard and his hair was very long in back and curly […] He said he was a poet and a little crazy and that he liked Buddhists. We didn't know what else he was so we decided he was a spy.” It was, of course, Allen Ginsberg, “a well-known beatnik,” as the reporter calls him.

Biographer Bill Morgan, in I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg, claims that the article was a hoax. He writes:

The newsmen were so bored waiting for something to happen that the day Allen left Saigon, they concocted a story that ran in the New York Times under the headline, “Buddhists Find a Beatnik ‘Spy.’” […] Of course none of it was true, but it made a colorful story. Since it was on permanent record in the New York Times, Allen spent his whole life denying the story.

It certainly feels like a prank, but I am not so sure it was. There are multiple reports across various newspapers over a series of several months that seemingly attest to the veracity of the account. They make note of the fact that the Buddhists were extremely paranoid and assumed almost any foreigner was a spy, so it is quite possible that the article merely played up a minor misunderstanding that occurred when Ginsberg attempted to meet with a Buddhist leader.

Moreover, there was some correspondence between Ginsberg and David Halberstam of the New York Times. Alas, Ginsberg’s letter is lost but in his archives there is a copy of Halberstam’s response, from which we can make certain inferences. It is quite clear that the “Buddhist Spy” story was at least partially true and that Ginsberg had been angered only out of embarrassment. Despite the fact that the article claimed he had left the country, it appeared whilst he was still in Saigon, and he was presumably upset at being portrayed as a hapless, borderline troublemaking beatnik buffoon.

In his reply, Halberstam tells Ginsberg that the poet was “a celebrity” and thus he had “sacrificed some of [his] privacy.” He continues:

as a celebrity arriving in this city and going to the heart of a major political dispute, you again put yourself in the public domain. If you had wanted (as a celebrity) to stay out of the papers then you had to stay out of the pagodas.

Given the situation the buddhist story and your arrival in the midst of it failure to send on a short piece would have been a sort of dereliction of duty; the fact that we liked you very much and found you a sympathetic friend does not excuse us from our jobs.

He goes on to say that the story helped convey “some of the peculiar atmosphere and suspicion of saigon to the outside world.” He is regretful that Ginsberg’s feelings were hurt but adamant that writing about his friend’s run-in with the Buddhists was the right thing to do. He ends his letter by inviting Ginsberg back and saying he “left many friends here.”

Ginsberg did return but only as a stopover when flying from Cambodia to Japan at the end of his trip. In total, he spent just seven days in Saigon. He summarised his time in a letter to his father:

I spent a week in Vietnam talking with opium poets & USIS directors & State Department spokesmen & Army public relations sergeants & most of all with newsmen & also the Buddhist priests. Horrible mess as you can read in the papers. Curious scene here [about] the reporters is that they are all young & relatively eager there, unlike most “hotspots,” so this a rare instance if you follow the politics war there, one can get a relatively straight account within the limits of assumed anticommunist slant & the euphemisms of ticklish situations. […] Anyway, I’m glad I saw what little I saw of that. Gave me a nervous stomach after a week.

Who were these “opium poets”? Possibly one was Vũ Hoàng Chương, sometimes called “Vietnam’s Li Po,” who wrote about opium and alcohol. Ginsberg also noted the name of and several major works by Xuân Diệu, a homosexual poet of significance, but he lived in Hanoi, so it is highly unlikely that a meeting could have taken place. Yet this remains a mystery for he wrote little of his time in Saigon and spoke only of Vietnam as a warzone, his own travels there second fiddle to his protests against America’s war.

In later years, as an outspoken anti-war activist, he liked to play up his time in the country. He included references to his Vietnam visit in biographical extracts used for his books, leaving readers to think that he had spent more time there and done more in the country than he really had.

Cambodia

As I have alluded to, Ginsberg’s journals from this part of his trip sometimes have an almost Burroughsian quality in that he seems to move from country to country like walking from one room to another. He was aware of this himself, telling his father:

Traveling by jetplane kind of a gas, you do get in and out of centuries from airport hangars & glassy modern downtowns to jungle floating markets & 900 year old stone cities in a matter of minutes & hours instead of weeks & months. Like space cut-ups or collages, one minute paranoiac spyridden Vietnam streets, the same afternoon quiet Cambodian riversides.

In his journal, he called it [j]umping in and out of space,” and noted the strangeness of hopping from Calcutta to Bangkok to Saigon in a matter of hours. He recalled “the / old elegance of the hitch thumb / in Texas past the valley / towns & the green river” and wondered whether transport would speed up to the extent that he could hop into the past.

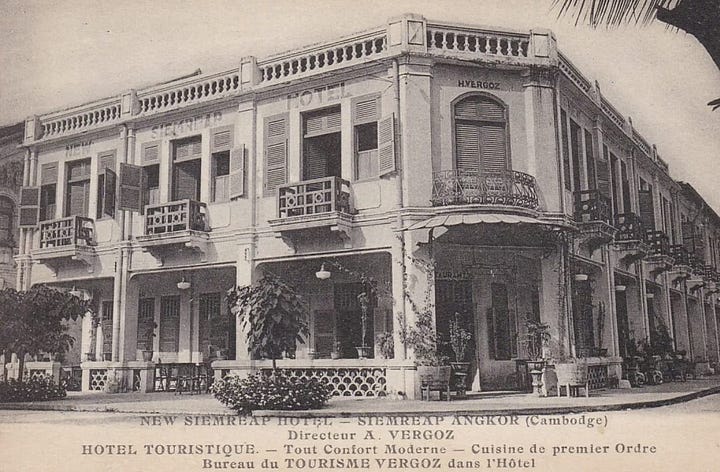

The “900 year old city” he is talking about is of course Angkor Wat, just north of Siem Reap in the west of Cambodia. He flew there from Saigon on June 7 and checked in at the New Siem Reap Hotel. The hotel had once been a gorgeous colonial building with tremendously high tourist standards but by 1963 was rather decrepit and Ginsberg paid just $2 per night for his room. Still, it was in the centre of the city, just ten minutes’ walk from the Angkor Museum and the Preah Ang Chek Preah Ang Chorm Shrine. The whole town, however, is some distance south of the Angkor temple complex—about forty minutes by bicycle.

For years, Ginsberg had dreamed of Angkor Wat, having seen various iconic photographs in books, and so he rented a bicycle and spent several days cycling around the area, admiring the ancient stone structures. He had pockets full of marijuana, which he smoked atop Phnom Bakheng and wandered in a stoned haze through the Ta Phrom and Bayon temples, transfixed by the countless faces and the trees growing through the stonework. He scribbled observations in his notebooks and these became the genesis of a poem he wrote on the night of June 10, just prior to leaving Cambodia.

The poem was called “Ankor Wat,” and yes that is A-N-K-O-R, with the G conspicuously absent. Why this was misspelled is a mystery, but there are at least two possibilities. Firstly, it should be remembered that the Khmer script is of course different from the Roman alphabet and thus any words rendered in Roman letters are merely a transliteration, with some transliterations more popular or common than others, and this changes over time, with globalisation and technological advancement generally bringing consensus. I live in Kampot, where it is still common to see the town name spelled both K-A-M and K-O-M-P-O-T, so perhaps Ginsberg encountered signage or documentation here that dropped the G. Indeed, some travel guides from that era used ANKOR, but I managed to find the travel guide Ginsberg actually had with him as he cycled around, printed by the National Tourist Office of Cambodia, and it spelled Angkor with a G. It is also worth noting that his journals from that period refer to Bangkok similarly, dropping the G so it says “B-A-N-K-O-K” even though his guidebook also used the conventional spelling.

Then there is the fact that he was terrible at spelling and even managed to misspell Siem Reap and Cambodia. It seems likely that his his publishers, perhaps lacking the historical or geographical knowledge required to make that change, left the unusual placenames as he had rendered them. Indeed, in his Collected Poems, published a few decades later, when editors would have more easily been able to check the spelling of these words, the title was changed to Angkor with a G, with references to Bangkok similarly corrected.

In any case, although it was named for the ancient temple city, the poem was primarily written in Siem Reap “in one night half-sleeping and waking, as transcription of passages of consciousness in the author’s mind made somnolent by the injection of morphine-atropine.” Ginsberg was attempting to write under the influence of morphine as a means of eliminating self-censorship in order to record a truer version of his consciousness. The only part of the poem not written in Siem Reap was a section composed of “notes taken earlier that day high on ganja on the roof of the temple of Angkor Thom.”

Many fans of Beat poetry and scholars of mid-20th century literature are unaware of “Ankor Wat” because it was never really considered a major work by this poet. Indeed, at a reading in 1969, Ginsberg told his audience that he had only ever read it aloud once before, something that is notable given how frequently he did public readings in the late sixties. Still, it was published in the first issue of Barry Miles’ Long Hair magazine in 1965, then in book form in 1968, before being included in his Collected Poems, so clearly he considered it of some value. Tony Trigilio argues that it is equal in significance to both “Howl” and “Kaddish” as it marks the point at which Ginsberg began to fuse his William Carlos Williams-inspired poetics with his later Buddhist ones. Bill Morgan, meanwhile, notes that it “sounded the beginning of a new fertile period of poetry for him.”

Indeed, the poem begins with Buddhist imagery and a clear statement of the poet’s interest in the religion:

Ankor – on top of the terrace

In a stone nook in the rain

Avalokiteshvara faces everywhere

High in their stoniness

In white rainmist

Slithering hitherward paranoia

Banyans trailing

High muscled tree crawled

Over the root its big

Long snakey toes spread

Down the lintel’s red

Cradle-root

Elephantine bigness

Buddha I take my refuge

Bowing in the black bower

Before the openhanded lotus-man

Sat crosslegged

Within just a few stanzas, however, Ginsberg makes reference to Hinduism, which has led to some criticism of the poem as yet another inauthentic Western surface reading of Eastern culture. In the fifties and sixties, of course, having some affinity for Eastern spiritualism and philosophy was quite trendy among Western hipsters and intellectuals, and so it was hardly unusual for people to take bits and pieces of Eastern mythology as it suited them. Yet those critics probably failed to note what Ginsberg had learned, which is that Angkor Wat was originally a Hindu temple and only later converted into a Buddhist one, and that the various construction efforts left behind both decidedly Hindu and Buddhist sections of the Angkor complex. In fact, even the parts built during the Buddhist era tended to use Hindu imagery, and it is worth noting that much of the Hinduism and Buddhism that made its way from India to Cambodia was adapted to incorporate local traditions and beliefs, so Ginsberg’s apparent confusion of the two religions (and let’s remember that Hindus consider Buddhism a branch of Hinduism anyway…) is perhaps not so much a misunderstanding as an astute and learned observation.

(There is not much on their website of interest, but the Angkor Wat Museum in Siem Reap has an incredible amount of information about the mixture of Hinduism and Buddhism and its adaptation to local culture under the various rulers of the Khmer Empire.)

A suggestion that Ginsberg was aware of Angkorian history comes from a line in the poem “Understand That This is a Dream,” which I mentioned earlier. He wrote, “Ankor Wat ahead and the ruined citys (sic) old Hindu faces.” It also seems obvious that he was attempting to fuse these ideas deliberately rather than accidentally, particularly in lines like “I’m taking refuge in the Buddha Dharma Sangha / Hare Krishna Hare Krishna.”

“Ankor Wat” is a confusing collage of Buddhist and Hindu mythology, alongside autobiographical detail, with observations taken at Angkor Wat juxtaposed against politics, with an emphasis on American imperialism in the region and the looming spectre of brutal war. In his final months in India, Ginsberg had begun to incorporate some of William Burroughs’ cut-up method into his work and had indeed begun to re-think what a poem should look or sound like, and this is evident here. It is not as accessible as the more coherent and transparent “Howl” and “Kaddish,” nor is it quite as obvious in terms of importance as “The Change,” a poem he wrote just one month later, which some consider a companion piece to this one.

To me, this poem is significant in terms of Ginsberg’s development as a poet and serves as sort of a missing link between earlier and later efforts. It highlights the poet’s fractured mind and his paranoia. I said earlier that his time in India completely changed him, and that these changes were percolating in his mind, “catalysing” in his words. In a sense, then, Angkor Wat was the setting for a poem about the poet’s uncertainty and his shifting worldviews in light of the expanded consciousness he had gained through travel. Though it feels like a Burroughsian cut-up, it is in fact a stream-of-consciousness record of a poet’s metamorphosis. We can see in him glimpses of the Allen Ginsberg who would only months later become the face of anti-war protest in the United States, who would espouse Flower Power and free love, and who would fight for gay rights and the decriminalisation of marijuana.

The poem is also in part an attempt to fuse the lessons learned in Asia with his knowledge of the West, and in particular his comparatively detached view of the United States gained through years spent abroad. It is an examination of how Eastern and Western thought could be combined, particularly in light of the war in Vietnam and in a period where colonialism had just ended but globalisation was beginning. It asked whether his homosexuality was compatible with Asian religious practices, and indeed it mentions many of his obsessions or ideas central to his character and asks how these could interact with Eastern spiritualism. We also see his racial and national guilt in lines like “Leroi I been done you wrong / I’m just an old Uncle Tom in disguise all along.” Here, he is referring to LeRoi Jones, who became Amiri Baraka—a black nationalist once part of the Beat movement. Ginsberg seems to imply that his silence as a white American man at the suffering of others is essentially complicity in the crimes committed against them, and he subtly invites comparisons to Nazis who merely followed orders. Echoing comments in his journals from this period, he asks whether he is a coward in this and other regards.

My descriptions thus far perhaps make it sound as though the poem could have been written anywhere, but it is perhaps in those moments where he discusses Cambodia and its ancient architecture that he is at his poetic best, and this is the locus or intersection point around which the swirling vortex of contemplations take place. It begins with a sketch of his surroundings and from there follows a stream-of-consciousness discussion that sees him making religious vows, lamenting his human frailties, and then discussing geopolitics, frequently returning to his surroundings, with the peace of Angkor juxtaposed against the backdrop of war, the reassuringly ancient temple and jungle set against the turmoil of internal uncertainty. Angkor Wat thus functions almost as a point of focus as in meditation where, after his mind wanders off on a tangent, he can return.

Let’s look for a moment at those instances where he describes the Angkor complex itself as these are indeed the most attractive parts of the poem. After a digression on regional politics, he says:

Monsoon riding thru the forest gate faces

Creepers silence on Ta-Phrom temple halls

narrow stone walk under sleeping trees—

rain on Ta-Keo pyramid—perfect faces

smiling ladies’ fiery headdresses in Thommanom

till passing the soda stand in forest arbor

ganja cigarette rolled in Terrasse Supérieur

rooftower by Ikon

of Buddha touching Earth

the burnt out incense sticks in the tipped can

I straightened and shoes off bowed

Of course, as most of us do when describing or otherwise documenting Angkor Wat, he frequently makes reference to the faces carved of stone and the iconic blend of trees and rock where it appears the jungle is claiming back the buildings. He refers often to physical features in terminology he would have been familiar with from other travels and readings—of Angkor Wat as like pyramids and sphinxes, and resembling the great stone cities of Latin America he had explored in the 50s. He jumps back and forth between Hindu and Buddhist iconography, between nature and that which is man-made. He notes of course the unforgettable image of trees overwhelming stone when he writes “Even that permanence warped cleaned in the Alice in Wonderland giant garden of Ta-Phrom.”

This idea of impermanence was important, for Ginsberg was in the process of overcoming a fear of death and decay that had consumed him for decades. My favourite line of his on this subject comes not from the poem “Ankor Wat,” but from a sentence he scribbled in a little notebook whilst leaving Siem Reap. On his way back to Saigon, he wrote, “Even if men were built of stone, they couldn’t live forever.”

The temples of Angkor Wat are vast and exploring them at a leisurely pace can consume days. It seems Ginsberg did little else during his three days in Cambodia except cycling around the ruins, sitting and contemplating their history, and wandering along the riverside in Siem Reap. On June 10, he wrote his poem and then flew back to Saigon.

Leaving Southeast Asia

Ginsberg spent one last night in Saigon. The following afternoon, he went to the airport and flew to Japan. Did he realise that a Buddhist monk, Thích Quảng Đức, had self-immolated in the middle of a busy intersection that morning? Journalist Malcolm Browne captured the act of protest in what would become the World Press Photo of the Year. It would become one of the defining images of the era. Ginsberg’s friend, David Halberstam, was present and had been warned the day before. Yet Ginsberg never mentioned it. In the future, he spoke often about Vietnam but only spoke of what he found in his research. He never drew upon his personal experience there.

Somewhere over Taiwan in the early evening he looked down upon the blue seas and marvelled at the tininess of the ships below him. He “saluted the coast of China [for the] first time” and lamented that he had not been able to stop in Hong Kong, something that had been in his original plans for the trip. But, he noted, he was “tired too tired to fight off plane,” another indication that his years of journeying were exhausting him, pushing him towards the final destination.

He would make it to China eventually, but that was twenty-one years later in a vastly changed world. He never reached Hong Kong or Taiwan, though. For now, he was heading to Japan, a country that would stun him with modernity and civility—then as now standing in stark contrast to the rest of Asia. Its cleanliness and politeness were a much-needed respite from the chaos and poverty he had witnessed over the previous two years.

After sleeping on the floor of Tokyo train station for a night, he took the train to Kyoto and stayed with Gary Snyder and Joanne Kyger for more than a month, relaxing, writing, meditating, doing yoga. It was a period of decompression, of thinking deeply, of internalising and processing all that he had seen and experienced and learned, resulting in “The Change” on July 18. Soon after, he flew to Vancouver and three weeks later returned to the United States, where he completed his two-and-a-half-year circumnavigation. By then, his views on life and poetry, as well as his perceptions of his own mind and body, had been profoundly altered.

He had managed this journey despite a perpetual lack of funds. He was a poet living on royalties and the goodwill of those he met along the way. He learned to travel cheaply, sometimes sleeping rough to save money, and wherever he went he attempted—usually with some degree of success—to learn about the culture and to make friends. He was good at picking up languages and foreign concepts, at meeting new people and adopting new ideas and methods for his poetry and activism.

I hope that in some small way this essay has contributed to an appreciation of those abilities, that even in his lesser travels—the ones generally overlooked or misunderstood—Ginsberg was doing the same things: taking in the local culture, talking with local poets, exploring and observing and constantly growing as a man and as an artist. I won’t pretend that Southeast Asia gave him as many lessons as India did, or France or Morrocco or Mexico, for that matter, but certainly this part of the world had more of an impact on him than is generally believed.

Ginsberg never made it back to Southeast Asia, which is a pity as he surely would have loved to have seen the rest of Thailand, Cambodia, and especially Vietnam, particularly in the post-war era as the country opened up. But it is a big world and he returned to new responsibilities and a hectic schedule as the most famous living poet. When he died in 1997, Ginsberg had visited fifty-five countries—an incredible achievement given that most of his travels happened in an era before cheap flights and when he was living on the meagre income provided by sales of poetry books. Even so, his final poem, written less than a week before his death, was a list of places he would never see or places he loved that he would not return to. From the late sixties onwards, almost all his travels were done on the back of organised reading tours, trips taken after his obligations ended. He only came back to Asia a handful of times, including his long-awaited journey through China, but had he been offered the chance to read in Southeast Asia, he surely could have jumped at the opportunity to return and explore more of this incredible part of the world.

Sources

There were very limited sources available regarding Ginsberg in Southeast Asia. For this book, I primarily used the files in his archives. For that, I am tremendously grateful to Tim Noakes at Standford University Library.

Additional sources include:

Baker, Deborah, A Blue Hand: The Beats in India (Penguin: New York, 2008)

Ginsberg, Allen, Collected Poems: 1947-1980 (Harper: New York, 1988)

Ginsberg and Orlovsky, Straight Hearts' Delight: Love Poems and Selected Letters, 1947-1980 (Gay Sunshine Press: San Francisco, 1980)

Morgan, Bill (ed) The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder (Counterpoint: Berkeley, 2008)

Schumacher, Michael (ed) Family Business: Selected Letters Between a Father and Son (Bloomsbury: New York, 2001)

I normally use extensive endnotes in my essays but Substack doesn’t seem to like that, so whilst I figure out a workaround please feel free to e-mail me with any questions about quotes and facts given in the above essay.

Terrific piece, David. Thanks as always for such great research. Never thought there'd be that much available detail on this period.

I'd like to revise my 'ran out of film' theory to "he probably lost it or gave it to Peter." Was just rereading Ginsberg's introduction to his Snapshot Poetics book and he states "As I left India in ‘63, I must have lost my Kodak Retina at some point or perhaps I gave it to Peter (Orlovsky) when we separated, because I bought a new camera in Hong Kong – a half frame camera – duty free, you know"

Hong Kong would have been a stopover from Saigon to Tokyo of course. I'd be curious to see whether Peter's archive has any evidence of having that Retina. No mention of a camera in Peter Orlovsky A Life in Words (Bill Morgan). For you camera spotters out there, that half frame referenced is an Olympus Pen D.

""Nervous stomach in Saigon not wanting to go to helicopter battlefields in rice paddies & watch Chinese bodies be blown apart?"" there's a political naivety in Ginsberg that takes me aback sometimes ... the tragedy in Vietnam was that it was Vietnames bodies being blown and burned apart.