The Self-Published Beats

A look at how the Beat writers used self-publishing to pursue their literary goals.

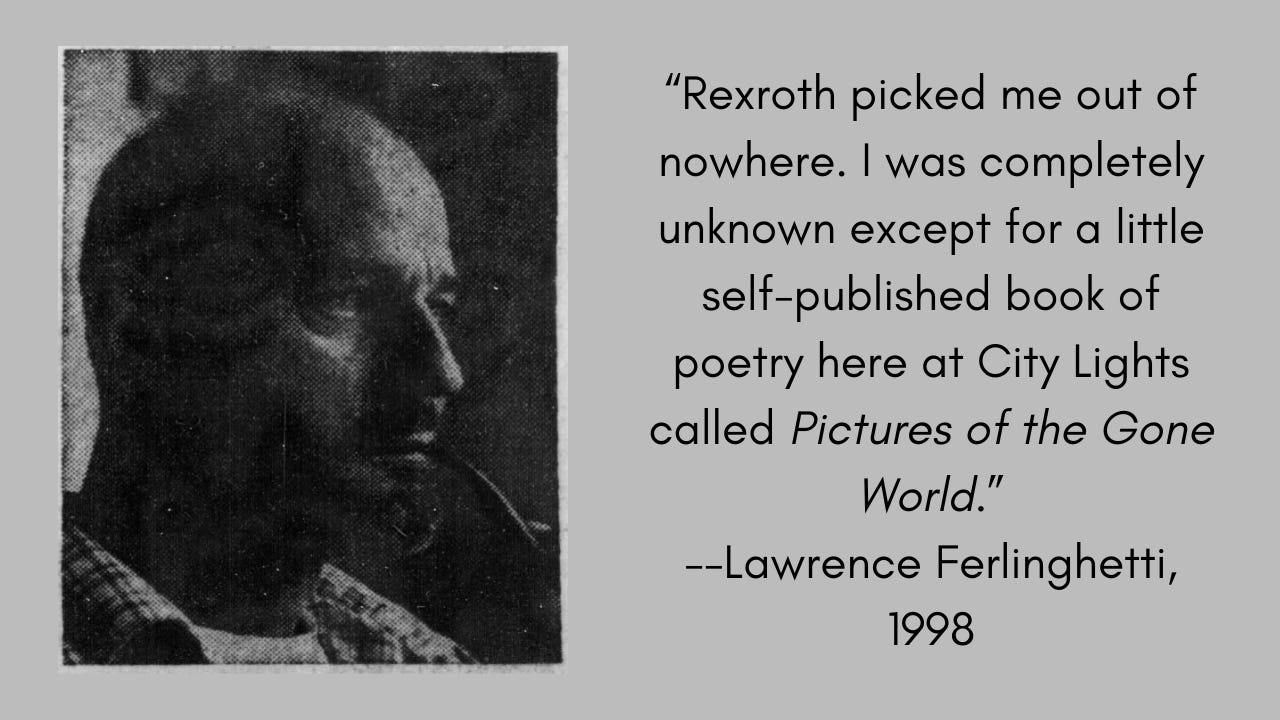

A few months ago, I was editing Leon Horton’s essay for Beatdom #25, which contained a quote from Lawrence Ferlinghetti that surprised me. He told a Paris Review interviewer in 1998 that Pictures of the Gone World was “a little self-published book of poetry.”[i] Of course, I knew that it was the first in City Lights’ Pocket Poets Series and, with Ferlinghetti as the owner of the publishing company, it was in a sense “self-published,” but somehow I had never thought of it that way.

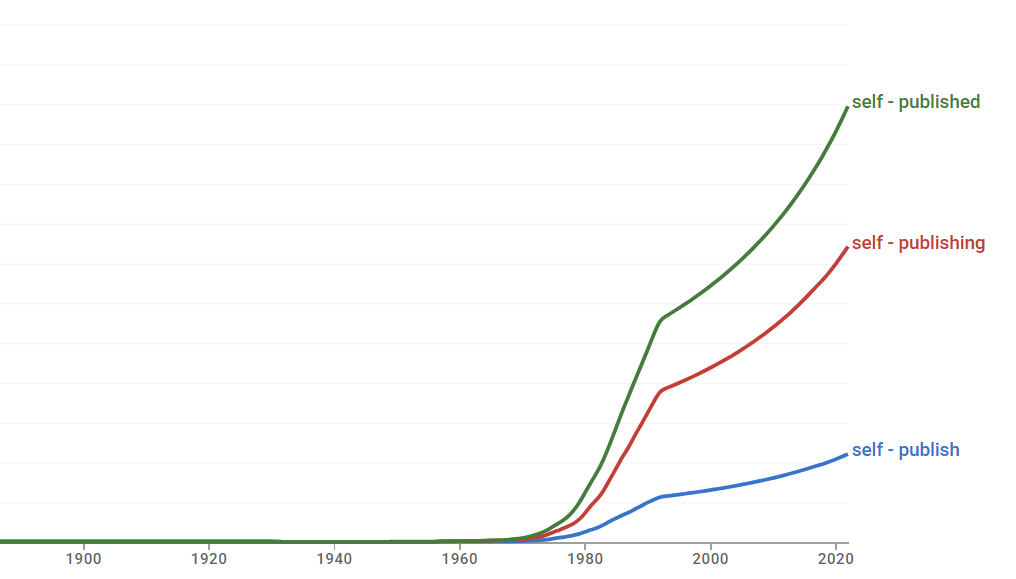

There is, in the 21st century, quite a degree of stigma attached to the term “self-published” in a way that has not plagued other art forms.[1] A band or filmmaker can distribute their own work and earn respect for rejecting corporate labels and being unwilling to yield control to people with largely commercial interests. Similarly, a visual artist can arrange their own exhibition and reasonably expect to be judged on the value of their work. However, for writers it is different. “Self-published” is sadly synonymous with “not good enough for a real publisher.”

This may be unfair but it is a widely held view. The average person has no interest in buying a self-published book and bookstores rarely stock them. Even if your self-published book is a great success, in some ways you have less respect as a writer than if you had a colossal failure of a book published by a major publishing company. It is better to sell 10 books through Penguin than to sell 1,000 via Amazon’s KDP.

Self-published authors often like to point to historical figures whose literary efforts offer validation for this means of producing a book. Walt Whitman is perhaps the most famous self-published author, and others include William Blake, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Mark Twain. Yet most examples of well-respected works tend to come from long before modern technologies lowered the barrier to entry. Back when it took more time and substantially more financial investment to produce a book, there was less distinction between a conventionally published book and a self-published one. There are by some estimates several million new books published every year whereas in Whitman’s day it must have been an astonishingly low number. Assuming you had the funds required to produce a run of your book, you could reasonably expect to have it reviewed and distributed, and with less competition there was more chance of success.

Self-publishing is often a fallback option for writers. Most would rather have their work edited by a professional and published by a traditional press with a team of distributors and publicists. After all, the writer’s primary job is writing books, not press releases. But of course there are other reasons. Sometimes writers take the self-published route as a means of evading censorship or editorial control. Whether they know from experience or simply fear the worst, they might wish to put out their own book as it fits their vision rather than risk having an editor change it or a legal authority confiscate and destroy it. This is often the case with radically unconventional books, which brings us naturally to the Beat writers.

The Beat writers generally produced work that was considered challenging by traditional publishing companies. Whether it broke with form, tackled difficult subjects, or used what was seen as obscene language, these books were viewed as legally and commercially risky in that conservative era. Even the writers who did not turn to self-publishing generally found themselves facing years of rejection. It is hardly surprising that many of them decided to skip the process and simply publish their own work.

This essay is going to provide an overview of that phenomenon, but first it is worth asking a seemingly pedantic question: What exactly is “self-publishing”? As will become evident in a moment—and is perhaps evident already due to the previous mention of Lawrence Ferlinghetti—it is not as clear a definition as one might think.

The Cambridge Dictionary puts it pretty simply, saying that self-publishing is

the process of arranging and paying for your own book to be published, rather than having it done by a publisher

However, in Ferlinghetti’s case, he was a publisher. He owned a publishing company. Does that count as self-publishing? Of course, any writer could theoretically establish a company and print their own book(s), but in Ferlinghetti’s case he very quickly arranged to publish the work of other respected writers. His book was also printed in fairly substantial numbers and reviewed quite prominently.[2] It was not self-publishing in the traditional sense but he did publish himself.

What of communal efforts such as the later little mags that saw one or two writers take on the role of editor and publisher to print their own work amongst that of their friends? What of rotating editorial and publishing duties among a cooperative endeavour? As we shall see, the Beats certainly engaged in this sort of venture and the results were notably less professional-looking than City Lights’ efforts, with far smaller print runs. The various dictionary entries all suggest it refers only to books, so can magazines, journals, and newsletters be considered? What if only one of several authors financially contributes? What if the author(s) only contribute(s) part of the resources required to publish a book?

Perhaps then it is more of a spectrum than a binary. On the left, there is traditional publishing through major presses and on the right you have poets printing copies of their own work on a mimeograph machine with hand-drawn covers. In between, you have collaborative zines and small presses run by poets.

For the purposes of this essay, let’s consider “self-published” to mean that a writer was active in publishing their own work, taking charge of either the cost or the physical process of printing and distributing it either as a book, a zine, or a broadside. When we define it this way, we can see quite a few examples.

Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs

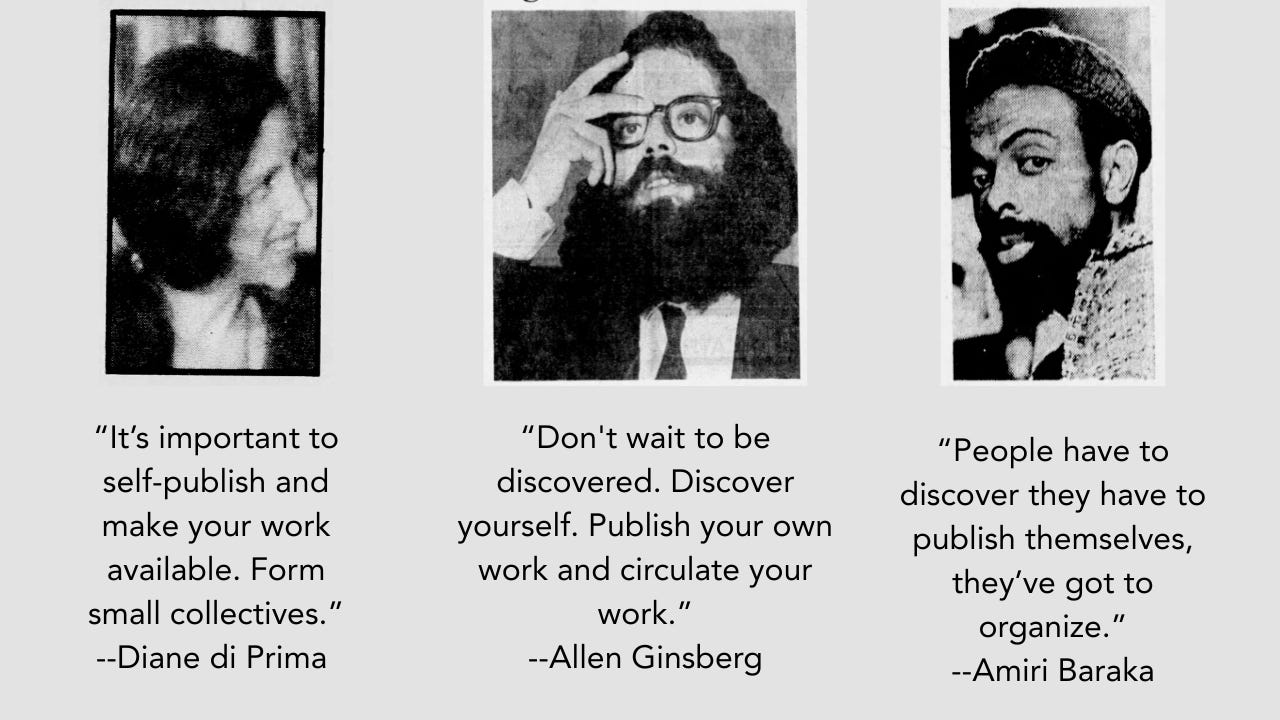

Of the “big three” Beat writers, Allen Ginsberg was the most enthusiastic about self-publishing. He once said:

Don’t wait to be discovered. Discover yourself. Publish your own work and circulate your work.[ii]

This was not merely advice he gave to others; it was something he personally practised. In July 1956, Ginsberg mimeographed 52 copies of Siesta in Xbalba whilst working at sea, and he sent these to friends around the country. On the front page, he wrote:

SIESTA IN XBALBA

and

Return To The States

by

ALLEN GINSBERG

dedicated to

Karena Shields[3]

As

Published by the Author

July 1956

Near

ICY CAPE, ALASKA

At the Sign of the Midnight Sun

Whereas we could debate whether or not Pictures of the Gone World was really self-published, and later publications fall into that same dubious category, here we have a book that is 100% self-published. Ginsberg wrote, edited, formatted, hand-printed, and distributed this text entirely by himself and proudly announced it as “Published by the Author” on the front page.

He sometimes included Siesta in Xbalba when listing his published books, and so it could reasonably be called his first book. Bill Morgan, however, has suggested that a mimeographed copy of “Howl,” printed in March of that same year, was Ginsberg’s “first book,”[iii] but this raises another question: What even is a book? Again, it seems like a pedantic question, but it’s not as easy to answer as you might think. Copies of “Howl” were certainly circulating in San Francisco from March 1956 onward and it appears there may even have been a copy at the 6 Gallery reading. Would these count as books? Ginsberg sometimes called Siesta in Xbalba a “book” and sometimes a “pamphlet” and he considered those earlier prints pamphlets as well, so there is no obvious answer.

I would say that in Ginsberg’s mind the early copies of “Howl” were merely accompaniments to his oral performances of that poem and that they were not books but typed and mimeographed manuscripts. The fact that he stapled and folded Xbalba into booklet form and used the word “Published” on the cover suggests to me that he viewed it as something quite different. Coupled with his later efforts to include it as the first entry in his bibliography, this seems to make a good case for Siesta in Xbalba as his first book. But whatever the case, his first book was a self-published effort.

What is interesting to note, though, is that Ginsberg did not self-publish this poem because publishing companies were ignoring him. He had certainly faced rejection, but as he cranked the mimeograph machine aboard his merchant marine vessel in July 1956, Howl and Other Poems was in the very final stages of publication by a real (albeit new and small) publishing company. He had other small presses keen to print his work, too, and he’d already been distributed as a spoken-word poet thanks to a record company. Ginsberg also had a number of publication credits in newspapers and magazines, so it is reasonable to assert that self-publishing was not a last resort. He was not some desperate, invisible poet with no other way of seeing his work in print. Nor was he doing it for the money, as the copies printed were sent to friends and family at his expense.[4]

Yet it was not as though Ginsberg was averse to publishing this poem by traditional means. In 1954, he sent a copy to Kerouac and told him to pass it to his editor, presumably hoping it might lead to publication. In 1957, Grove Press seems to have promised to publish it as a 17-page stand-alone title and then in 1958 Charles Olson apparently passed it to another publishing company that had seemed eager to print it. Evidently, Ginsberg did not believe this poem had some quality particularly suited to self-publishing. So why did he self-publish it in such a small edition?

We can scrutinise Ginsberg’s letters from the summer of 1956 for clues and it is not difficult to see why he might have chosen to self-publish one book in addition to having another published by City Lights. During these months, he was a little upset with Ferlinghetti, who on at least a few occasions made decisions against Ginsberg’s will, and the poet felt frustrated that his artistic creations were being altered without his consent. He was already aware of the potential legal troubles and hated that certain words were to be replaced by asterisks. A few weeks before mimeographing Xbalba, he got an early copy of Howl that had been misprinted due to a misunderstanding, which prompted the following:

This being my first book I want it right if can. Therefore I thought and decided this, about the justifications of margins. The reason for my being particular is that the poems are actually sloppy enough written, without sloppiness made worse by typographical arrangement. The one element of order and prearrangement I did pay care to was arrangement into prose-paragraph strophes: each one definite unified long line. So any doubt about irregularity of right hand margin will be sure to confuse critical reader about intention of the prosody. Therefore I’ve got to change it so it’s right.[iv]

He felt “rich” at this point in his life and offered to personally pay for the mistake to be rectified. We can infer from this that he wished to have more control over the final appearance of his poems. He wanted his exact words set on the page in just the right way and noted several times in letters that he was unhappy with the way Howl and Other Poems had come together. He told Kerouac, “Next time will take my time and not be so eager to finish a book.”[v]

Following the publication of Howl and Other Poems, Ginsberg rapidly ascended to a degree of fame known by no other poet since. Due to his influence, he was able to exert some control over small presses and editors in order to have his poems published as well as work by his friends, and he did not have to make too many concessions when this happened.[5] In fact, a lot of his early work—which had previously not been deemed good enough—was later published because his fame was sufficient to ensure sales.

From this point on there was generally little reason for Ginsberg to self-publish, but there was at least one exception. In 1970, he decided to self-publish a political work: “Documents on Police Bureaucracy’s Conspiracy Against Human Rights of Opiate Addicts & Constitutional Rights of Medical Profession Causing Mass Breakdown of Urban Law & Order.” This was published in an edition of 300 copies. It was likely done due to the lack of commercial interest. It is included in Morgan’s bibliography of the poet but obviously differs quite a bit from the other works mentioned in this essay.

Between writing “Howl” and having it published, Ginsberg briefly contemplated starting his own press. In December 1955, he wrote his brother regarding concerns over obscenity laws. City Lights had already agreed to publish Howl and Other Poems but it was unclear whether copies printed abroad would be allowed into the country or not. This led to him explaining that he was in the process of putting together a press to publish work by Kerouac, Burroughs, and himself. He intended to print books in Japan and then import them, but worried that customs laws would prohibit this.

Ginsberg’s Beat press was never established but he certainly helped his friends find publishers to print their work. He had done this with Burroughs’ first novel, Junkie, which he helped sell to Ace Books. Later, he helped put Burroughs in touch with other editors and publishers, some of whom were artists in their own right, operating small publications at least partly as a means of printing their own work.

William Burroughs certainly benefited from the collaborative and cooperative countercultural small press and little mag scene of the 1950s and ’60s but he did not get into self-publishing. He benefited from those who had the initiative to do this and he created certain publications, but these were not what you would call self-published books. In one sense, this is a little surprising. He was a subversive writer whose work was often described as “unpublishable” before some daring publisher took a chance on it, but he merely wrote what he wanted even when that meant spending years writing for the benefit of his friends and not getting his work published. He was also an advocate of DIY art culture and the adoption of new technologies as a means of evading control, yet when it came to publishing he seems to have had a more conventional approach: the artist creates work and others disseminate it.

To be quite honest, when I first began planning this essay, I thought Burroughs had self-published a few works but as I looked in more detail I realised I was remembering publications within publications. Burroughs made his own newspapers and magazines, titled “The Moving Times,” “The Burrough,” and “The Apomorphine Times,” but these were published in other publications, including Jeff Nuttall’s My Own Mag (a self-published zine).[6] He made a mock-up issue of Time and produced a publication called APO-33: The Metabolic Regulator, but these were printed by small presses. Whilst he clearly did not self-publish these, they are interesting in relation to this topic for they saw Burroughs move beyond the role of author and into that of editor and designer, before handing them to people who were sometimes self-publishing their own works alongside his.

This was all in the sixties but we can see even as of the late 1950s that Burroughs appreciated the little-magazine concept enough that he nearly started his own alongside Gregory Corso (with Ginsberg possibly as co-editor). This would have been called Interpol but it never came to pass. Their letter, however, implies that Corso and Burroughs expected Ginsberg to do the grunt work:

Bill and I are set on doing a magazine, INTERPOL, “the poet is becoming a policeman”—and our content will be of the most sordid, vile, vulgar, oozing, seeping slime imaginable. We only want the most disgusting far-outness. For first issue Bill has in mind: Bowles (his most disgusting); Tennessee Williams (his most); and your bubbling, gooey cocaine writing; and Stern’s[7] most humiliating, and Kerouac’s most maudlin, etc. So we are determined to do this because like Bill says, we’re policemen and we can’t help doing such things, it ain’t our faults. So we decided to make you co editor of suggestion and fund-raising; it will be your task (thus to insure this historic venture) to collect the most hideous of material, and money, lots of money; go to Don Allen, Kerouac, everybody, and demand they send Bill Burroughs money for this ghoulish enterprise.[vi]

Unlike Ginsberg, Burroughs was not good at self-promotion and lacked the organisational skills and business acumen required to self-publish. Instead, he merely created original art and relied on his various supporters to do that for him. Thankfully, he found the editors of small publications willing to print his work and then had several books published due to the support of yet more risk-taking editors. He became an infamous underground writer thanks to Olympia Press, John Calder, Auerhahn Press, Jeff Nuttall, Barney Rossett at Grove Press, and an uncountable number of figures in the mimeo revolution. (There is much at RealityStudio about these publications.)

Jack Kerouac seems to have had even less interest in self-publishing than Burroughs. He worked for years to hone his skills as a writer but always looked to publication by a major press as the goal. I see no obvious examples of him contemplating anything else (except for childhood newspapers he made). Even when he collaborated with Burroughs on And the Hippos Were Boiled in their Tanks, it did not cross his mind to self-publish or go with a small press. He always aimed high and whilst his art was radical, his attitudes towards publishing were more traditional. You can see in his letters that he wanted his work printed by a major publishing house and then turned into a movie, and that he would change agents or try other editors whenever he was rejected. After writing Hippos, he told his sister:

An agent has taken pains to make our contact at Simon and Schuster and we should know whether or not they will publish it within two weeks. If they don’t want it, we simply take the book to another publisher, and so on ad infinitum. […] But if the book is not published, and nothing happens to anything I write, I frankly will be up against a stone wall again.[vii]

In other words, it was conventional publishing or nothing.

Baraka and di Prima

I’ve mentioned a few times the role of small presses and little magazines and the fact that “self-publishing” sometimes meant collaborative publishing efforts with one or more writers taking the role of editor and publisher. This was the case with Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka). Baraka founded Totem Press in 1958 with his wife Hettie Jones and the same year they started Yugen magazine. Again, this was not a simple effort of self-publishing because they published work by an array of writers, one of whom was Baraka. Hettie Jones was not published by either the press or the journal but still considered Yugen “self-published.”[viii]

In the first issues, we can see a number of Beat writers: Philip Whalen, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Gregory Corso, and Diane di Prima. According to Steven Belletto, “di Prima in fact frequently assisted in the production of the magazine.”[ix] She also had the first book printed by Totem Press: This Kind of Bird Flies Backward and the next year Totem published Jan 1st 1959: Fidel Castro, which included various poets including Baraka. Totem would later publish some of the same Beat writers who had appeared in Yugen and would also put out Baraka’s first book, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note.

Baraka and di Prima edited the self-published journal/newsletter The Floating Bear, which appeared in 1961. It also published many works by Beat and Beat-related writers, and of course it included poems by the two poet editors. Di Prima would later establish The Poet’s Press, through which she published several of her own books and many by other poets.

Clearly, di Prima was an advocate of self-publishing. In 1999, she told David Meltzer:

It’s important to self-publish and make your work available. Form small collectives. Start small. You have to remember, you don’t have to think of going national. Each small city and its surrounding area is the size of a country from a long time ago. Handle it that way. […] Part of what we’re hypnotized by the media is that we have to hit millions of people at once. Back then 117 people got the first Floating Bear. And I sold 1,000 copies of my book out of the stroller wheeling Jeanne around New York.[x]

Baraka published through big presses, small presses, and self-published his work. It was not a case of starting small and going big, though; he made the choice to cease working with major publishers in 1970 but then went back to them later, and he periodically chose to self-publish works. Asked about why he continued working with William Morrow in 1978, he replied with typical bluntness: “Because of the money. When they do publish something, it gives me more money.”[xi] He went on to explain that he enjoyed self-publishing and could sell a few thousand copies of a book, but he liked the money that came from big presses. He felt big presses looked down on him, demanding to see his manuscripts before agreeing to publish them in spite of his having published numerous books before. That same year, but in a different interview, he spoke of the importance of self-publishing and in doing so echoed Ginsberg’s and di Prima’s quotes above: “People have to discover they have to publish themselves, they’ve got to organize.”[xii]

Kaufman, McClure, and Others

Alongside Yugen and The Floating Bear stands Beatitude. Founded in 1959, this was one of the essential Beat little magazines and it featured a great many of the movement’s great writers: Ginsberg, Kerouac, McClure, Corso, ruth weiss, Philip Lamantia… but can we consider it self-published?

As Steven Belletto writes in The Beats: A Literary History, “Editorship of Beatitude is a complicated question, as it was the brainchild of a number of people who alternated taking the lead editing particular issues.”[xiii] The first issue proclaimed: “Edited cooperatively by various types from Grant Street, Mill Valley, and other scenes,” and that it was published at the offices of John Kelly, but in fact it was printed at the Bread and Wine Mission. (At one point, it was even printed by City Lights.) A famous photo shows Eileen and Bob Kaufman looking at the first printing of the journal with a mimeograph machine in the foreground, suggesting they had at least some role in printing that first issue, with William Margolis[8] using the machine. These people, alongside Allen Ginsberg and John Kelly, seem to have come up with the concept and they seem to have rotated editorial and publishing duties perhaps alongside others.

The first issue contained poems by both Bob Kaufman and Margolis (but not Eileen Kaufman or John Kelly), and Ginsberg appeared quite often, so we could perhaps say this was partially self-published. In any case, it falls loosely onto our spectrum.

The journal is extremely important as it rejected the mainstream publishing world against which the Beats proudly stood. The name and its content and style seem like efforts to re-appropriate the Beat label (recently distorted into “beatnik”) and align it with the idea of religiosity put forth by Kerouac and Ginsberg. The poets published were a who’s who of the Beat Generation: Ginsberg, Kaufman, Ferlinghetti, Corso, Kerouac, McClure, Whalen, Lenore Kandel, ruth weiss… With hand-drawn covers and littered with spelling mistakes (many of which were deliberate), it embodied the rough self-published style of the mimeo revolution. It was printed in San Francisco and was distributed throughout the city (although mainly in North Beach) but many of its more famous contributors (such as Ginsberg) were by now located in other parts of the world.

Of course, Yugen and Beatitude and the other publications of the late 1950s did not emerge spontaneously and without precedent. They grew out of the San Francisco Renaissance, which arguably started with the 6 Gallery reading,[9] but they built upon a number of earlier publishing endeavours, which were offshoots of a smaller and looser pre-6 literary scene. We should briefly mention William Everson and Untide Press, which inspired Ferlinghetti’s Pocket Poets Series—or at least its covers. It was in a Conscientious Objector’s camp that Untide (partially run by Everson) serialised Everson’s “War Elegies” and then collected and published them as a mimeographed booklet.[xiv] Given Everson’s later ties to the Beats and the press’s influence on San Francisco poets, it should not be overlooked here. In the 1940s, there were at least two other self-published poetry magazines in the Bay Area: Circle and Ark. These were edited and run by poets who included themselves along with their friends and more famous writers they admired, such as William Carlos Williams and Henry Miller. The poets and publishers and editors involved were later part of the mid-to-late fifties scene: Robert Duncan, Bern Porter, Thomas Parkinson, and others. This was before the Beat Generation, of course, but it’s worth mentioning because Michael McClure resurrected Ark in 1956. In what was called Ark II / Moby I, he printed some of his own poems alongside work by other local and/or Beat writers, including Kerouac, Ginsberg, Snyder, Whalen and Denise Levertov.

Although the Bay Area scene was small and had no real impact on the national literary environment in the 1940s, it rapidly expanded with Allen Ginsberg’s reading of “Howl” and his joining forces with Gary Snyder and co at the 6 Gallery, resulting in the San Francisco Renaissance, which is largely what allowed the creation of so many little mags and self-published and small-press-published books in the late fifties, and their success in turn led to the vibrant little publishing scene of San Francisco in the 1960s. There are many examples of little magazines published in the 1960s that were at least in part vehicles for the editor/publisher to print their own work. There was Fuck You/ A Magazine of the Arts, which was operated by Ed Sanders and mostly published his poetry in the beginning. (This led to book-publishing ventures, with works by Burroughs and Ferlinghetti printed by Sanders’ press.)

When we expand “Beat” to include the related countercultural writers, we see particularly in San Francisco that it became common to print your own poetry and sell it or give it away. John Wieners’ Measures was an editorial effort until issue three, at which point he included a poem of his own, alongside other writers including Kerouac who very much were Beat. I realise Richard Brautigan is not a Beat writer (even though he was in Beatitude) but he embodied this idea with his various self-publishing efforts, including printing poems on packets of seeds. He and Ron Loewinsohn co-edited and published Change, a journal that featured their poetry and their photograph on the cover, and which published Beat and Beat-related writers such as Philip Whalen, Joanne Kyger, and Robert Duncan. Loewinsohn said the following about that era of self-published zines, which I think explains why so many great writers were published in these often crude, stapled, hand-illustrated publications:

But more important than the quality of their contents was the fact of these magazines’ abundance and speed. Having them, we could see what we were doing, as it came, hot off the griddle. We could get instant response to what we’d written last week, & we could respond instantly to what the guy across town or across the country had written last month. Further, many poets who didn’t stand a Christian’s chance against the lions of “proper” publication in university quarterlies or “big-time” magazines could get exposure &, more importantly, encouragement &/or criticism. For all its excesses it was a healthy condition.[xv]

A comment by Steven Belletto in The Beats: A Literary History builds interestingly upon this:

Little magazines were often the first venues in which many Beat writers were published, and looking at them from issue to issue, journal to journal, we discover the tissue of the late 1950s literary underground: not only the visions of individual works, but also a sustained cross talk among editors, readers, and writers that exemplifies the emergence of a new sensibility.[xvi]

I realise that not all little magazines were self-published but quite often there were writers acting as editors and/or publishers of these publications, printing their own work alongside that of their peers. It was not always because these writers couldn’t get published in major magazines or by big publishing companies but sometimes it was because they were part of a fast-paced scene, not unlike the blogosphere of 2008-2011 or today’s Substack community. Writers expressed themselves and got immediate feedback and they wrote in response to one another, with a culture emerging from this environment—a culture that rejected the academic poetry in prestigious journals and chose a form that suited it. They were not just oppressed, unheard, and too obscene to publish elsewhere… they were self-publishing because that was how they wanted to express themselves. It was the medium that best fit their message.

I could go on but the point was never to provide an exhaustive list, even if such a task were possible. We could drag this beyond the hippies to Hunter S. Thompson’s Aspen Wallposter and the zine culture of the seventies and eighties, but hopefully this essay functions as a discursive overview of the previously overlooked links between the Beats and self-publishing.

Final Thoughts

We tend to think of self-publishing as a single author printing their work and then distributing it, but if we are to take Ferlinghetti’s categorisation of Pictures of the Gone World as self-published then we can surely include the various efforts by writers to publish themselves as part of small presses and little magazines. This seems to be supported by comments by Diane di Prima, too, who was a pivotal figure in the Beat and post-Beat small press scenes, so perhaps it’s possible to look at some of the iconic little magazines of the era as self-published.

When we look at it this way, there are multiple links between the Beat Generation and self-publishing. It is true that some of the more successful writers did not actively self-publish their work, but they usually contributed writing to publications that were in some way self-published. We can see that there were various reasons for this method of distributing literary works, including it being the only realistic option for an unknown poet, but also as a means of evading editorial interference and censorship. We can also see that it was simply part of the Beat and countercultural ethos and that self-published works formed a sort of artistic and philosophical communications network, with writers not only expressing themselves but responding to one another, building upon new ideas. With some publications printed weekly, it was a fast-paced means of establishing a new culture.

We are lucky these writers chose to explore this form of publishing, for without it the Beat Generation would’ve looked very different.

Footnotes

[1] Tellingly, the longest section of the Wikipedia page for Self-Publishing is the one titled “Stigma.”

[2] In the first two years, they put out books by Kenneth Rexroth, Kenneth Patchen, and William Carlos Williams. It seems Ferlinghetti planned to publish e.e. cummings as part of this series but that never happened. His name was often mentioned in early advertisements for the series. See Don Heneghan’s book, City Lights Pocket Poets Series 1955-2005, for more details.

[3] We have a long essay about the incredible life of Karena Shields here.

[4] He instructed Ferlinghetti to sell copies of Xbalba for $0.50 each and donate the proceeds to Michael McClure, who was then working on Moby (another self-published venture), so it was not merely a private pamphlet for friends and family.

[5] Even so, Ginsberg generally stuck with small presses and it was 1985 before he signed with a major publisher—Harper & Row.

[6] According to Maynard’s Burroughs bibliography (p.132), Burroughs self-published part of “The Burrough” in a publication called Ex 3, but as Jed Birmingham notes in RealityStudio, this is likely a mistake. It seems to be a magazine edited by Italians and likely Burroughs gave them something that Nuttall did not include in My Own Mag. Birmingham says, “it is doubtful that Burroughs had direct involvement with the ‘issuing’ of the magazine.”

[7] Jacques Stern, a friend and patron of the Beat writers, did eventually self-publish a novel with Burroughs’ approval. It was called The Fluke.

[8] Margolis was also the editor and publisher of The Miscellaneous Man, a controversial journal targeted by police at the same time as Howl and Other Poems.

[9] See Beatdom #25 for more on the SF Renaissance and A Remarkable Collection of Angels for a history of the 6 Gallery and its famous reading.

Endnotes

[i] Plimpton, George (ed.) Beat Writers at Work: The Paris Review (Random House: New York, 1999) p.343

[ii] Raskin, Jonah, American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and the Making of the Beat Generation (University of California Press: Berkeley, 2004) p.xvi

[iii] Morgan, Bill, I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg (Kindle edition, no page number)

[iv] Morgan, Bill, and Peters, Nancy J., Howl on Trial: The Battle for Free Expression (City Lights: San Francisco, 2006), p.43

[v] Morgan, Bill, and Stanford, David (eds.), Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters (Viking: New York, 2010) p.328

[vi] Harris, Oliver (ed.), William S. Burroughs: The Letters: 1949-1958 (Penguin: New York, 1994) p.396

[vii] Charters, Ann (ed.), Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters: 1940-1956, p.86

[viii] George-Warren, Holly (ed.), The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats: The Beat Generation and American Culture (Hyperion: New York, 1999) p.52

[ix] Belletto, Steven, The Beats: A Literary History (Cambridge University Press, 2020) p.202 (of my ebook copy)

[x] Meltzer, David (ed.), San Francisco Beat: Talking with the Poets (City Lights: San Francisco, 2001) p.21

[xi] Reilly, Charlie, Conversations with Amiri Baraka (University Press of Mississippi: Jackson, 1994) p.143

[xii] Conversations with Amiri Baraka, p.123

[xiii] The Beats: A Literary History, p.211 (of my ebook copy)

[xiv] William Everson: The Life of Brother Antoninus, p.47-48; see also William Everson: A Descriptive Bibliography, 1934-1976, p.16-17

[xv] Calonne, David Stephen, Diane di Prima: Visionary Poetics and the Hidden Religions (Bloomsbury Academic: New York, 2019) p.69

[xvi] The Beats: A Literary History, p.201 (of my ebook copy)

I recall finding Diane Di Prima's 'Calculus of Variation' (Eidolon Press 1972) in a thrift shop back in the late 1990s or early 2000s. I found the contents quite different from the Di Prima poetry I was familiar with – I think I'd read an early selected by then – very dense and difficult. Which was probably why she went the self-publishing route with it!

Such an interesting article David. I self published two things in the 1970s Space Magazine (underground political) and Dreams(music, poetry, manifestos) Now I publish through a “vanity” or “subsidy” commercial press (Atticus) and Kevin Ring’s The Beat Scene. Important to get the work out somehow. The vanity publishers do pr etc but it’s expensive and doesn’t work all that well.