Beat & Damned: The Death of Natalie Jackson

An essay on the death (and, to some extent, the life) of Natalie Jackson, who died November 30, 1955.

Where is Natalie Jackson?

Natalie's dead and gone.

Just like you and me, poor boy,

A little later on.

-- Gary Snyder, Dec 2, 1955

In researching a book on the 6 Gallery reading of 1955, I naturally came upon a number of references to Natalie Jackson, who was in attendance the night Ginsberg first read “Howl” and who passed away in shocking circumstances a little less than two months later. Her death was an event that partially broke up the West Coast Beat scene in the way that David Kammerer’s death had temporarily broken apart the East Coast Beat scene eleven years prior.

However, hers was a name only mentioned as the girlfriend of Neal Cassady and the tragic suicide victim who supposedly plunged six storeys to her death. Then of course she appears in several famous photographs, looking happy and in love with the handsome Cassady, who is at the centre of each picture—always a magnetic force drawing the broken and curious, a whirlwind of destructive energy ripping across the American landscape.

When it dawned on me that the anniversary of her death was approaching, I decided to write a short essay about her. I began to consult the usual sources but I was surprised to realise that there was hardly anything about her in articles, essays, and books about the Beats. Even in a book specifically devoted to the women of the Beat Generation, there was only a single paragraph. No one seemed to know where she came from or who she was. That would certainly make sense if she had only been a random person who passed through the Beat group that year (like Peter Duperu,[1] a North Beach junkie whose name often crops up in letters and journal entries), but a look beyond the colourful biographies of these men suggest that she was more than just the pretty face that caught Cassady’s attention that year.

In fact, Cassady is on record as saying she was the love of his life while Allen Ginsberg wrote about her often, dreamed about her frequently before and after her death, penned a beautiful elegy for her, and included her in a version of “Howl” as yet another “best mind of his generation destroyed by madness.” Kerouac referred to her in several books and even said that she was a writer. Gary Snyder—in heretofore unpublished words—wrote highly of her intellect in a short but touching journal entry that included the short poem that prefaced this essay. Her death shook all of them though perhaps it did not change them as much as it should have.

Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but if Natalie Jackson was not that important, if she was just a random bohemian who kept Neal Cassady busy in bed for a year (which is how she’s depicted in most books), then why was she eulogised in poetry and prose by three of the most important writers of the century? These men were all sexist to varying degrees but even then—in those misogynistic times—they all noted the strengths of her mind rather than fixating on her looks and sexual habits.

There seemed to be a notable disparity between the way these men thought of her and the way she was depicted in books about those men. Of course, biographers, scholars, and historians cannot give dozens of pages to each person who enters the life of their primary subject, but certainly Natalie Jackson has been conspicuously absent from accounts of this period aside from the horrific details of her death. Moreover, it seemed to me rather exploitative that someone could be deprived of a fair accounting of their life when we seem to revel in the gory details of their final moments. And then of course there is the laziness in reporting that so frequently surrounds Beat history, which is to say that the accounts of her death are embarrassingly inaccurate in spite of a wealth of available information. It appears to me that the story of her passing was so well known that those who have written about it merely repeated a few details without checking them and then added further embellishment. I will explain how she died later, but for now let’s just say:

No, she did not fall six storeys to her death.

No, Jack Kerouac was not the last person to see her alive.

No, she was not high on amphetamines (or anything else) when she went to that rooftop contemplating suicide.

No, she had not robbed Carolyn Cassady of $2,500 or even $10,000 of life savings.

No, she did not jump from the roof of her own building, or any roof for that matter.

No, a police officer did not leap and grab her, getting only a handful of robe, causing her to fall to her death.

No, she was not entirely naked when the police scooped her dead body off the street… nor in fact was she even dead at that point.

As always, early Beat historians took Kerouac’s novels at face value, practically rewriting his texts with no other sources but a thesaurus, Then, for a half century, others have merely cited those original texts. (It is precisely the same problem as the 6 Gallery reading, which occurred weeks before her death, has faced. More on that mythmaking here.) Few have bothered to look into the readily available details of her death and almost no one has looked into her life… although admittedly that is much harder to do.

When I realised how badly her life and death had been reported in books about the Beats, I decided to do her some justice by writing a more detailed essay on her. I wanted this to be the next instalment in a series of long, exploratory essays that unearth previously overlooked or misunderstood parts of Beat history. I hoped to provide a portrait of her life before and during her relationship with Neal Cassady. But alas, I have failed. She proved too elusive. This was something discovered by Jonah Raskin, who I believe is the only person who wrote about her in any detail before now. He noted that “Natalie lived a largely invisible life until her death in November 1955,”[i] and he is right.

I began digging into all the contemporary sources I could find—newspapers, letters, journals, government documents, and so on. I thought I had unravelled the mystery and traced her life in the East… but after many days of searching, I realised I had been following the life of the wrong Natalie Jackson! In fact, there were several Natalie Jacksons born in New Jersey in 1931. Those women led comparatively privileged lives that continued after November 30, 1955.

I did, however, find enough to write a more detailed account than has previously been written and to correct many mistakes. That was depressingly easy to do even if it was time-consuming. Most of the relevant facts were simply there; no one had bothered looking until now. Perhaps of greatest interest was a journal entry by Gary Snyder from shortly after her death. This helped confirm Jackson’s status in the group and the fact that she had not merely been some vapid blonde (or redhead) who liked to screw and didn’t bother the boys when they were having fun. She had possessed many admirably traits that remind one of another doomed woman of the Beat Generation: Joan Vollmer. She was smart, original, creative, and rebellious.

So this essay is essentially a failed effort but I hope that it has done her some small amount of justice. Perhaps someone with more resources can take it and build upon it, unearthing more about her life in New Jersey. There has to be something… Even after researching all of this, I have many questions: What went on in her mind? What did she write about? Who was she before she came to the West Coast? I don’t know, but what follows is my modest effort at bringing some justice to someone who was a victim of Neal Cassady’s sociopathic tendencies and then a further victim of shoddy scholarship.

This is going to be another long essay (13,000 words), so as usual I am dividing it into chapters so that people may navigate or resume reading after a break if they wish.

A Slim Biography: The Life of Natalie Jackson

I am embarrassed to say that there is very little I can tell you about the life of Natalie Jackson before she succumbed to the fatal gravitational pull of Neal Cassady. But here is what I have been able to uncover…

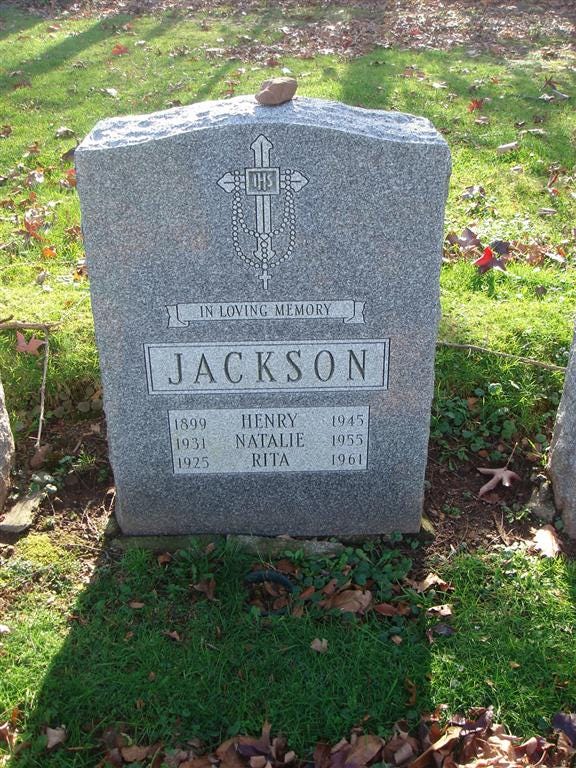

Natalie Jackson (no known middle name) came into this world on September 6, 1931, the daughter of Henry James and Irene Constance Jackson (née Oakley). She was born in Newark, New Jersey, and as of 1940 her family lived in East Orange in a rented property with a value of $25,000 (worth $563,000 today). Her father earned $1,440 per year (about $30,000 in 2024) working as a chauffeur. She was the middle of three children, with a sister about 6 years older and another sister 4 years younger.

Natalie’s father died in 1945. He had been eligible for the draft and so it is possible he was killed in the final months of the war, but I can find no records. Maybe he never served at all and simply died at home in the U.S. In any case, he was about 45 years old when he passed away and whilst this is a tragically young age, he lived a longer life than two of his daughters. Natalie would die at just 24 and her older sister Rita passed away at about 36. The youngest sister Patricia died last year at the age of 87. (If only someone had thought to write this before now; perhaps Patricia would have been able to tell us something…)

By 1947, when she was about 16, Natalie was at Good Counsel High School in New Jersey, a Catholic school (its name seems to be short for “Our Lady of Good Counsel”). There isn’t much information about her but she is second from left in the fifth row of this photo:

She had a job at some point, working for Kresge department store in Newark.[ii] This was a discount store that sold clothes and home goods.

Natalie was married but to whom I do not know (Jackson was her maiden name, which evidently she resumed using after her divorce). Another Natalie Jackson from Newark born in about 1931 was married in Philadelphia in 1951 but she seems to have been alive and well after our Natalie died in late 1955. A second Natalie Jackson born in 1931 was married in New York that same year but again this is not our Natalie. Census data for 1950 is hard locate due to there being a great many Jacksons in the New Jersey area and newspaper records show nothing about her at all. As Raskin said, she was largely “invisible” in life.

There are clues, though, and these are tantalising. According to a note in one of Allen Ginsberg’s letters, Jackson was in Greenwich Village at some point before moving across the country and there she dated Stanley Gould, a hipster friend of Kerouac’s. No evidence exists for this except a single note by Ginsberg, but he was living with Jackson at the time and had no reason to lie about that claim, so it is likely true. Thus, Jackson probably moved from New Jersey to New York in the early 1950s. One imagines she found the bohemian environment enthralling and perhaps heard about an even more liberating scene on the other side of the country… but that’s purely my speculation.

At some point, she divorced, but again it’s hard to say when that happened although given her age and her sudden move across the country, it likely occurred in 1953 or ’54. In either the summer or autumn of 1954, she travelled from the East Coast to the West and settled in San Francisco, which was rapidly becoming the destination for artistic types and those generally opposed to the pressures and emptiness of mainstream American culture.

This is where we start to find at least some meaningful evidence of her life.

Neal’s Gal: A Real Gone Chick

Natalie Jackson will sadly always be known as one of Neal Cassady’s many girlfriends and, through Neal and the suicide he drove her to, she was eulogised by Jack Kerouac in The Dharma Bums as “a real gone chick.”[iii] Perhaps that’s how she wanted to be known then, for by all accounts she was madly in love with him and he with her, and quite a few people depict her as wild and fun-loving. However, this is just one dimension of her character, one chapter of her life… the final chapter, sadly.

I suppose most people leave little trace—or at least they did before the digital age—and so maybe it is not surprising that Natalie Jackson seems barely to have existed until she entered the lives of a group of men who would have an outsized impact on the culture, and who famously chronicled their own lives and left vast archives and thousands of pages of correspondence. Jackson is mentioned many times in the journals and letters of Allen Ginsberg, who in late 1954 was living in San Francisco, where he would stay for about two years.[2] He had arrived in the city a few months earlier after a long trip through Mexico and a short stay with the Cassadys in San Jose.

Some sources state that Neal Cassady met Natalie Jackson in October 1954 and whilst this is not impossible, it does seem rather unlikely. Ginsberg first wrote of her in a December 29 letter to Jack Kerouac, in which he described at length (but in confusing, unclear language) the scene he had found himself embroiled in. He had been dating a woman called Sheila but had recently met a young man called Peter Orlovsky through the painter Robert LaVigne. The story is well known to Beat enthusiasts: One day, Ginsberg bumped into LaVigne at Foster’s Cafeteria (a late-night eatery popular among nocturnal hipsters) and they went back to LaVigne’s home, where Ginsberg saw a large nude portrait of a handsome man. He fell in love immediately and was amazed when the model walked in from the next room. Apparently, Ginsberg returned about a week later with Cassady and the same thing repeated itself. A nude portrait of a redheaded woman caught Neal’s attention and then in walked the model herself. It was Natalie Jackson.

The story sounds a little too good to be true, but what matters is that by the end of December, Ginsberg was in love with Orlovsky and Cassady was in love with Jackson. Ginsberg writes that Cassady had been sleeping with her for about a week, so their relationship had been ongoing since a little before Christmas. In that same letter, Ginsberg wrote that Natalie had been “here for four months in the back,”[iv] so she probably came to San Francisco about the same time as Ginsberg, which is to say at some point in August or September. He is likely suggesting that she occupied “the back” room of a building on Gough Street, an “artist bohemian pad”[v] rented by LaVigne. The painter, who had been sleeping with Orlovsky but had lost interest, invited Ginsberg to replace him and for a brief period the Gough Street house was home to the two couples: Ginsberg and Orlovsky in one room; Cassady and Jackson in another. They had a shared kitchen that functioned as a social area and here they would smoke pot and goof around, with Neal and Natalie sometimes switching clothes as a gag.

Ginsberg describes not just this crossdressing game but a scene of great reverie, with Neal and Natalie at the heart of it, constantly screwing and smoking and laughing. He wrote:

Neal is giggling and playing games with redhead in other room down the hall, I’m in love with twenty-two year old saint boy who loves me, lives there too, but terrible scene is here.[vi]

The “redhead” Ginsberg mentions is of course Natalie. (Some called her blonde but most seemed to think of her as a redhead—she was probably somewhere between the two, a strawberry blonde as it were.)

It is interesting that he calls the scene “terrible” because otherwise he describes it as rather fun if admittedly chaotic. At that point in his life, however, Ginsberg was prone to periods of depression and possibly manic depression given his extreme swings in mood, and his descriptions of places and situations tend towards euphoria or despair. He was certainly conflicted about Orlovsky, who was primarily straight, and LaVigne, who soon came to regret giving Peter away. On New Year’s Day, he wrote in his journal that it was “[t]he first time in life I feel evil.”[vii] Or maybe it was just the messiness of life on Gough Street. The house was filled with pot smoke and frenetic (often sexual) energy—both of which tended to follow Cassady—and it all reminded Ginsberg of the early Beat scene in New York ten years earlier. Now he was feeling old and nostalgic and this reversion to youthful hijinks perhaps contributed to a feeling of uncertainty.

There was much sex in the Gough Steet house and it seemed that everyone was screwing everyone else. Ginsberg had a girlfriend and felt guilty for cheating on her (even though she had slept with Al Hinkle). Neal was of course married to Carolyn but now dating Natalie and he had a long history of seeing several women at the same time. LaVigne drew pictures of Natalie in bed with Ginsberg and Orlovsky, suggesting that the three had had sex—something certainly within the realm of possibility given that the two men enjoyed group sex, Natalie was very open to sexual experiences, and Neal did not mind letting his friends fuck his girlfriends. (Around this time, he would encourage Kerouac to sleep with Carolyn to alleviate his own guilt at seeing Natalie, and he offered another friend, Pat Donovan, as a “surrogate husband”[viii] for the same purpose.)

Perhaps it was merely posed, but one of these illustrations is intimate, suggesting love and sex. Natalie has one arm over Peter’s naked stomach and Ginsberg, holding what appears to be a post-coital cigarette, has an arm around Peter’s shoulder. Peter’s hands clasp both Natalie’s and Allen’s. This illustration appears on page 14 of Straight Hearts’ Delight and it is erroneously dated as “summer 1954.” In fact, it was from the first half of 1955. On page 90 of that same book is a second illustration likely from the same date. It is a cruder drawing in both senses of the term. In the first, all three people are recognisable but here there are not at all. All three sets of genitals are visible but hastily rendered, making them unclear, and Natalie’s face is extremely unflattering. Whereas the first image suggested love, intimacy, perhaps cohabitation and friendship, this one more strongly implies the messiness of the physical act. Perhaps the aim was showing two sides of sex.

As we can see, then, Natalie was a model of sorts. Ginsberg mentions her appearing in various paintings and illustrations although only a handful survive. I cannot find the supposed nude painting of her that Cassady saw but several line drawings are in his archive (including the two from Straight Hearts’ Delight). She also appeared in a huge painting LaVigne was working on that winter but it’s not even clear if he finished it. The painting featured many of the regulars at Foster’s. Ginsberg wrote in 1958:

Toward the end of our stay in San Francisco there was the great idea of a huge historic picture of the scene in Fosters, with the now dead Natalie Jackson seated naked in a chair perhaps, and all the people we knew, fixed in some sweet and final attitude in eternity on his canvas. It came out of sketches he’d done already, one which I grabbed, and an earlier fine narrow canvas (his landlord alas took for rent)—all sorts of space tricks with mirrors and elliptical spacejumps between huge nearby coffeecups and faraway San Francisco businessmen-lautrecian-groaner soup eaters—added to this the lovers of Fosters in their time. Well god knows where this painting is progressed to by this time, he wrote he had done more and I wish I could see it.[ix]

Whether or not it was finished is unclear but evidently it progressed to a certain point because Carolyn Cassady later wrote that Neal had shown it to her, obviously omitting the fact that he was cheating on her with the nude at the centre of the painting.

Natalie is conventionally described as beautiful and one would assume so given that she was Neal Cassady’s love interest for about a year—this being a man who seemingly could get any girl he wanted—but others have called her unattractive, and as Jonah Raskin pointed out in an excellent but sadly now unavailable essay on her,[3] she seems rather keen to hide her face in photos. Only six photos seem to exist of Jackson (excluding the high-school yearbook picture I unearthed and embedded earlier in this essay) and in the one where she is facing the camera, we can see that she is not what one might call conventionally attractive. Kerouac noted that she was “bony, handsome,”[x] which seems rather a backhanded compliment. I mention all this not to add to the already impressive pile of sexist garbage written about her but rather to provide some insight to her character, for she comes across sometimes as filled with confidence and elsewhere as lacking it, and perhaps a mix of these brought her into the Beat world in search of validation, for she evidently became a model and a participant in group sex.

Beautiful or not, Jackson appealed to the men in that Beat group not because of her physical appearance but rather her personality and intellect. Ginsberg called her “cool, intelligent, warm,”[xi] and elsewhere wrote that she was simply “beat.” Gary Snyder said he “admired […] her quick mind.”[xii] ruth weiss called her “a wild fun redhead.”[xiii] Kerouac said she was “a real gone chick and friend of everybody of any consequence on the Beach, who'd been a painter's model and a writer herself.”[xiv]

She had a life outside of these Beat men, of course. Ginsberg mentioned in his journals her having a friend called “Nemmie.” It’s not a common name, so one wonders if it’s the same person for whom Jack Spicer wrote a poem (“For Nemmie,” My Vocabulary Did This to Me, p.158) or Nemmie Frost, whom Ginsberg mentioned in “Nov. 23, 1963: Alone” (Collected Poems, p.33-334). In that same poem, he refers to “the Ghost of Natalie,” so perhaps… In any case, it seems Natalie may have known Nemmie before the others, or at least that’s my reading of a brief journal entry Ginsberg made in January 1955.

She seems to have been full of energy and conversation. Ginsberg wrote about her in April 1955:

she beat, keeps hanging around to talk to me I can’t stand it (tho she’s a hip redhead frantic lost days), but I’m too weak to listen to lost talk, too tahred tahred.[xv]

Anyway, Natalie Jackson was clearly part of the San Francisco Beat scene and not just a peripheral figure. She lived in the same building as Cassady, Ginsberg, and Orlovsky for a while and participated in their shenanigans and sexual activities. According to Hinkle, she was well known for giving excellent blowjobs[xvi] and some have mentioned her having a penchant for amphetamines. Also included in this scene were Peter Duperu, Gerd Stern, and Al Sublette. Cassady sometimes took Jackson on road trips up and down the California coast, once driving to Los Angeles and back in less than 24 hours, seemingly on a whim, and earning multiple speeding tickets during the journey. He even planned a trip to New York with her, but this does not appear to have happened.[4]

This all gives the impression of a wild and fun scene with a degree of intellectual stimulation. However, Ginsberg was fairly depressed and as we saw earlier he called it a “terrible scene.” Elsewhere, he said there were “circles of Dostoevsky in this house.”[xvii] He was surrounded by people he loved, experimenting with sex and drugs… so what was not to like?

Maybe it was just Ginsberg’s hangups. His journals are unclear but he seems to have been frustrated with his own personal situation, which of course was tied to Natalie due to his living arrangements, as well as trouble writing and a lack of money. However, Natalie may have had more to do with his negative perceptions of the “scene” than simply occupying a nearby room. Even from an early stage, she seems to have been quite paranoid. Despite generally being seen as a fun person, and despite most accounts of her death being precipitated by a sudden turn towards paranoia, there are hints early on that she had perhaps struggled with mental health issues.

In January, Ginsberg wrote “Natalie getting shrewd axe toward Neal.” It’s not obvious what he means exactly but he tied it to Sheila, adding “w. Sheila’s counsel—Sheila suspects all men.”[xviii] Presumably Natalie felt upset about something Neal had done or about their relationship in general. This is hardly surprising given that he was married to Carolyn and often returned on weekends to see his wife and family. Another hint that all was not well in Natalie’s world is that when Ginsberg confided in Peter that he was depressed, Peter replied, “We are all suffering the same, Natalie, Robert, Sheila, myself, you.”[xix] The idea that perhaps Natalie felt guilty about Carolyn is hinted at in this cryptic letter from Cassady to Jackson from January 5:

We both goofed, I feel, want to feel, such sympathy . . . thru having done it myself many times, over & in the bowl, like in youth a green or too strong cigar. . . . Beside which comes to mind the times of realizing fully the agony of other New Year party drunk friends. . . . Most particularly at the exact moment just before the actual regurgitating begins . . . for you, (the sympathy) as the pity one entity would have for another who is reaping similar karma as he himself must face, has faced.[xx]

Ginsberg also wrote of a “sordid paranoia scene”[xxi] and said that when they went out drinking in North Beach, they met a man whom Natalie suspected of being an undercover FBI agent.[xxii] Whilst not impossible, this was a few years before law enforcement really began to monitor countercultural activities in the area. Ginsberg later recorded either a dream he had of Natalie or a dream Natalie told him. In any case, it also involved the FBI. She seems to have been worried about them busting her for possession of marijuana. Here, she is described as being “hopeless, restless, helpless.”[xxiii] This again suggests that her supposedly sudden turn towards suicide was in fact part of a longer battle with inner demons.

Ginsberg soon moved out of the Gough Street apartment and into his own place on Montgomery Street, but Neal and Natalie came on weekends and would occupy his bed, leaving him frustrated. (Remember that Ginsberg was very much in love with Cassady and so his unhappiness stemmed not only from the inconvenience of being booted from his own home.) Cassady and Jackson were broke as well, so Ginsberg had to lend them money. Writing about this, he noted in his journal that “Natalie [is] being shunted out,”[xxiv] but once again it’s not clear from the context what he meant. Was Neal perhaps trying to get rid of her? Were others in the group pushing her away? At this same time, he wrote to himself:

How alike are Natalie & DuPeru—and the germane genuine problems of the beat & damned.

What a prescient comment, given how Natalie’s life came to an end later that year. Peter Duperu was a toothless junkie hipster on the North Beach scene. Even less is known about him than Natalie but Kerouac describes him in Desolation Angels as wildly eccentric, staying up all night and picking up strange objects. He shoplifted badly and said strange things like “The moon is a piece of tea.”[xxv] A famous photo by Allen Ginsberg shows Duperu, Cassady, and Jackson “horsing around” (Ginsberg’s words) above the Broadway tunnel. They’re all laughing and happy, no sign of the depressing paranoid scene Ginsberg depicted in his journals.

The photo can be viewed here. Given the length and style of her hair, it was likely taken around the same time as this photo (also by Ginsberg). Perhaps I am reading too much into it, but they seem to show a stark difference in mood that perhaps reflects the different accounts of Natalie—fun and open but paranoid and moody, etc. It brings to mind a comment Helen Hinkle made after meeting Jackson: “She just sat there, not saying a word, staring into space—catatonic, I'd say.” She added that she was “strange” and “weird.”[xxvi]

The most famous photo of her, and perhaps the most famous of all Ginsberg’s photos, is this one, in which Natalie and Neal embrace each other outside a cinema, the marquee listing films including “The Wild One.” Ginsberg likely took this photo and framed it as a comment on Cassady’s character. However, he was not oblivious to the woman in the picture and he annotated it:

Neal Cassady and his love of that year the star-cross’d Natalie Jackson conscious of their roles in Market Street Eternity

After looking at movie listings for 1955, I believe the picture was from February, which seems to be when those three films would have been playing at the same time. Although she likely battled mental health issues all that year, she was probably happier early on and February was likely one of the high points, during which time she was passionately in love with Neal and he with her.

By June, she seems markedly less happy albeit once again it’s hard to know exactly what Ginsberg meant when he wrote:

Natalie’s screaming beard spotting wall sex images flashing thru fuck with everybody Dhyana dream

Perhaps this was because in May Neal and Carolyn Cassady had finally separated. He had been attempting the impossible for months—visiting his wife periodically and maintaining the illusion that he was living with Ginsberg in San Francisco in order to work on the railroad as a brakeman. Carolyn was a smart woman even if her tolerance for men’s bullshit often put her in horrendous situations. Did Natalie feel guilty about breaking up a marriage? Had she perhaps somehow not previously known of Neal’s wife? Did Neal’s attitude towards her change after they lived together full-time? Did the end of Neal’s marriage (or so it seemed at the time) perhaps remind her of the end of her own? These seem impossible questions to answer, but they might well explain her protracted deterioration.

Carolyn surely must have known Neal had another lover but she found out for sure when she discovered photos of them together alongside love letters. The photos were not pornographic but Neal was groping Natalie in one of them, and the letters made absolutely clear what was going on. One from Natalie to Neal read:

DEAR N.:

We’re stimulated by pleasurable unexpected surprises. i.e. I love you more now, but better. In the everyday I haven’t tried that yet or in another vein. The grass looks greener, etc.

I know your body—It’s a mystery to me. I half forget about you then your body surprises mine; another awareness of a solution to the non-existent a moment before mystery disclosing itself.

I know every inch—mole, blemish, hair, scar, pore yet don’t think of them really (except maybe a tenderness for a favorite or outstanding one) until I see them again—then the flash of memories, and have probably felt with my hands or touched and sensed and tasted all the feelings and your reactions to touch—and the different tastes of the various parts of your body yet it excites me more than someone or something that is as yet unexplored to me. I love you.

N.

At 5 a.m. this sounds like a label on a bottle of English lice killer or care and treatment of scabies. Is best over absinthe.[xxviii]

Let’s pause for a moment and digest that. As a love letter, it is hardly derivative or classical or girlish or anything one might expect. The long lines of reduced grammatical form, rolling with the breath, are oddly Beat. The sudden switch to humour at the end, too, is unexpected and the references are shocking, witty. I don’t want to overstate the similarities but it is noteworthy that this letter would not seem out of place had it been written by one of her male Beat friends. As Kerouac had noted, she was herself a writer and indeed had apparently been a fan of Kerouac, even recording herself reading a piece he published in early 1955 as “Jazz of the Beat Generation.”

Carolyn read Neal’s reply next, which proved beyond any doubt how her husband felt about this other woman:

I dreamt of you last nite; rather, it was 2 dreams, one night, one morning, among other things—including verification of validity of authentic vibration between us, as opposed to simple sex hunger, actually similar level of mind. I met your San Jose girl friend in the train yard & suggested I take her to you just so I could see you again. That was the main part of the dream, the desire to find you again.

[…]

I believe it quite possible, but rare, to feel a perfect lover, one with whom you are one because each match, as radios attuned perhaps . . .[xxix]

Neal’s letter was unfinished and unsent but the damage of course was done. That last line must have hurt unbearably. She was his “perfect lover.” The idea of her as more than simply satisfying “sex hunger,” too, and being of a “similar level of mind” must have added to her pain (and it also adds credence to the idea of Natalie Jackson being more than simply the beautiful lover suggested in most Beat histories).

Carolyn asked him if he wanted a divorce and he said no. “But Neal,” she explained. “I just can’t take anymore, please. You don’t love me at all, what could be more obvious? Why on earth must we stay married? This is no marriage.”[xxx] Neal was afraid of ending his relationship with her even though he was fully committed to another woman. On some level, he seemed to believe he could maintain both of them.

Drawing upon some indescribable strength inside her, Carolyn continued to play the role of housewife even as she knew her husband was living in another city with another woman. He lied and told her he was staying with Ginsberg and Orlovsky, working on the railroad, but she knew the truth. He came home about once every two weeks when he received his paycheque. He would play with the kids and act as though nothing was wrong, but one morning—May 10—Carolyn woke to find he had gotten up early and left the house. Beside her was a cowardly note:

Dear Ma: I hate myself, and you know it. But I looked long and hard at my son last night, & I fully realize my responsibilities, plus I am in full fear of my failings that once a man starts down he never comes back— never. N.[xxvi]

Was this why Natalie Jackson seemed to turn from a fun-loving young woman into the “catatonic” one who was “screaming” and “paranoid”? It’s hard to say given the lack of evidence. Most books about the Beat figures active in 1955 understandably focus on Kerouac’s time in Mexico City and Ginsberg’s breakthroughs leading to “Howl” or the meeting of Snyder, Whalen, McClure, Ginsberg, and Kerouac just prior to the 6 Gallery reading. References to Natalie Jackson focus almost exclusively on her death, with some mentioning her as Casady’s girlfriend. Ginsberg’s texts (which I have relied on primarily here) show that she stayed with Neal throughout the year, very much in love. She was there, she was a participant in the scene, but she was just out of sight in terms of those writing later on.

From what I can discern, she was troubled but again it’s hard to say how bad it was or why she was this way. Years later, Ginsberg wrote of her “Benny hallucinations”[xxxii] and her being a “victim of amphetamine paranoia suicide.”[xxxiii] Yet after her death, a toxicology report said there was nothing in her blood, so her mental breakdown was psychological rather than pharmaceutical in origin. Ginsberg wrote that she was “out of the running.”[xxxiv] What did he mean by that? Did he think Neal was going to go back to Carolyn or move on to a new girl? Neither are impossible due to Cassady’s personality, but they seem unlikely. He was certainly infatuated with her. Gerald Nicosia wrote that Natalie was “Neal’s de facto wife, satisfying his sexual needs more successfully than any other woman,”[xxxv] and this seems to have been true. Years later, he would go as far as to say she had been his “only true love.”[xxxvi] Maybe it was just down to Natalie being insecure. Brenda Knight, in Women of the Beat Generation, said “Natalie was a sensitive girl who became easily agitated when Neal was not around.”[xxxvii] It’s hard to know how she could’ve known this fact and there is almost nothing else about Jackson in that book, but perhaps it’s true.

On October 7, we know for certain where Natalie was and that she was happy and in love. She was in the audience at the 6 Gallery poetry reading, where Allen Ginsberg would first read part of “Howl.” Kerouac described the scene in The Dharma Bums:

Among the people standing in the audience was Rosie Buchanan, a girl with a short haircut, red-haired, bony, handsome, a real gone chick and friend of everybody of any consequence on the Beach, who'd been a painter's model and a writer herself and was bubbling over with excitement at that time because she was in love with my old buddy Cody. "Great, hey Rosie?" I yelled, and she took a big slug from my jug and shined eyes at me. Cody just stood behind her with both arms around her waist.[xxxviii]

Had she not died some weeks later, this image would likely have been the one that endured. And perhaps it was one that captured her well, for certainly it seems she was the sort of woman who enjoyed that socio-literary scene. Both Ginsberg and Kerouac noted that she enjoyed avant-garde literature. She not only had enjoyed Kerouac’s “Jazz of the Beat Generation” (published earlier that year) but had been recorded reading it aloud. The piece was partially drawn from On the Road and referred to Dean Moriarty, the man who now stood with his arms around her, deeply in love with her.

In November, she was at least well enough to find a somewhat lucrative job. Drawing on her experience working in a discount department store back East, she now switched to a high-end one in San Francsico: Joseph Magnin (often just known as JM). Jonah Raskin notes that JM was “where Marilyn Monroe bought a wedding dress for her marriage ceremony to Joe DiMaggio in January 1954.”[xxxix] One newspaper report said that she had “worked briefly last month [November] as a cashier-wrapper”[xl] whilst another said it had been seasonal employment.[xli]

Signing Her Fate

Neal Cassady had many vices: sex, drugs, and cars were the most famous of them. But another of his vices, and the one that would lead to Natalie Jackson’s death, was gambling. At some point in 1955, he became obsessed with a supposedly fool-proof method of betting on horseracing. Carolyn Cassady, in her memoir Off the Road, explained:

You simply bet the third-choice horse, the theory being that the first and second choices were often over-rated, but the third choice was likely to be just as good, and by the law of averages it had been proven to be so—the third choices won frequently and consistently, and the odds were better. The trick, of course, was to bet enough money each time to cover any previous losses. Neal began with two dollars, and the system usually hit before he lost very much, thereby getting all his losses back plus the winnings. He had been doing this for a month or so (I groaned) and had begun to keep records by checking the race results daily in the paper. So far, the longest period of loss was eleven consecutive races. Well, no, he hadn’t had the capital to cover that... “But think, if I had! Honestly, darling, think of it. Now, in time, you see, I’ll have other guys covering all the tracks in the country —all the races! But it has to be done scientifically —no getting interested in the horses, no listening to tips from touts. It’s hard work, not fun.”[xlii]

This was late September, so he must have been gambling like this since about August if his statement and Carolyn’s memory are correct. We know that Natalie went to the track with him, as did Kerouac on occasion. For Kerouac, it was amusing but how did Natalie feel about her boyfriend engaging in such obviously destructive behaviour?

In fact, Gerald Nicosia claims that it was not Neal’s system but rather “Natalie’s sure-fire system of betting the third-choice horse double-or-nothing in every race.”[xliii] It is certainly possible but it seems hard to prove this and it is more consistent with Neal’s personality than Natalie’s. Interestingly, Burroughs heard about Neal’s reckless gambling from Tangiers and—somehow assuming it was a system based on dream premonitions—wrote him a warning:

Tell Neal from me to drop the bang tails. You can’t beat it. Dream hunches are not supposed to be used that way. You understand, Neal? You know what horse is going to win, but you can not use that knowledge to make money. Don’t try. It’s like fighting a ghost antagonist who can hit you but you can’t hit him. Drop it. Forget it. Keep your money…[xliv]

Burroughs didn’t need supernatural powers to see into the future here and Neal did lose his money. In fact, he lost all of the money that he and Carolyn had invested and he did so in an even more unethical manner than one might expect.

Many books about the Beats refer to Neal enlisting Natalie’s help in stealing Carolyn Cassady’s life savings but in fact the money belonged to both of them and had been earned by Neal. It totalled about $10,000 and was the result of a compensatory payout for a railroad accident he had suffered, part of which had been wisely invested. As they had a joint bank account, in order to withdraw the money, he needed Carolyn’s signature and so he took Natalie along with him to pose as her so that he could continue with his betting system. They acquired the money quite easily and Neal predictably lost all of it.

A few weeks later, Carolyn received a phone call. It was the bank manager in Cupertino. “Mrs. Cassady? I’m sorry to bother you again, but when you and your husband were in the other day to withdraw your money, I forgot one paper for you to sign.”[xlv] She rejected the bank manager’s suggestion that she have Natalie arrested because she did not want Neal to go through the legal repercussions. In fact, just as she had done when she found him in bed with Ginsberg a year earlier and found out about Natalie some months prior, she stayed calm and tried to think positively (relying on a number of religious advisors to help her with this superhuman feat). Anyway, the money had been Neal’s, she told herself, and even after it had been lost they were financially better off than before his accident, so it wasn’t a huge deal. Still, she was angry and wrote him the following note for him to find when he returned home that evening, knowing that if she stayed up to confront him, it would only lead to anger:

Dear Neal: In case I’m too sleepy to keep you awake tonight, I’ll talk at you by this less painful method. What did we say about getting greater tests as we grow stronger? It sure happens fast. The good Lord decided I should know about your deal in Cupertino, too. I keep wondering why, but am going on the assumption it’s to give me an “opportunity” to overcome rather than one to get even. Poor guy, when he called I said, no, we hadn’t gone East nor had my mother died. I really thought he had the wrong Cassady. Anyway, when he persisted, I had to admit ignorance of the deal (clever boy, why must you make things so complicated?). He wanted to sell the stock immediately and swear out a warrant for Natalie’s arrest. I therefore gathered the children from their schools and dashed over there to countersign the whole thing and told him to hold it. He assured me he’d be standing by if I ever wanted to bring the guilty party to justice. I tried to explain that you thrive on punishment, so nothing to do but try something different, and hope the horses come in. No wonder your parties are so renowned, wow! By the way, is the identification card of mine she used something I’d miss? She did very well, I must say, but could use a bit more practice on the C’s.

Like you say, I ain’t dead yet.

Guess I’ve said all I can keep from. Wake me if I won today. C.[xlvi]

Neal was apologetic the next day but refused to acknowledge that his system didn’t work. He said his mistake was listening to touts instead of his “scientific” process. However, whilst Neal and Carolyn dealt with this shocking act of fraud and betrayal with relative restraint, it was a different matter entirely for poor Natalie Jackson. By all accounts, the guilt she felt from her participation in the theft pushed her into a state of total mental breakdown.

Natalie’s Last Night on Earth

Although there are few sources about Natalie Jackson’s life prior to 1955, and Ginsberg’s accounts from that year are fairly incoherent, various people have testified to her final days and the fact that she was in a state of extreme depression and paranoia that had pushed her to either self-harm or a failed suicide attempt.

It is certainly possible that her mental state in late November 1955 was partially due to other factors. Indeed, as I have shown, she had evidently displayed paranoid tendencies throughout the year. She was also recently divorced and living far from her family, so she probably lacked a support network, and her father had passed away ten years prior, so that might have been on her mind. But there is no escaping the fact that Neal Cassady had pressured her into committing a serious felony and that together they had done something phenomenally unethical to a woman whose life they had already damaged through their infidelity.

On November 29, Jack Kerouac went over to Neal and Natalie’s apartment at 1051 Franklin. He recounts this in The Dharma Bums.[5] Natalie had been introduced in chapter three of that book, when Kerouac described her and Neal at the 6 Gallery reading. At that event, which took place on October 7, they had appeared perfectly happy but now everything had changed and Kerouac was disturbed. (He had likely seen her several times in between but these meetings are not mentioned in his book for the sake of a more focused narrative.) Kerouac tells us that “she was suddenly skinny and a skeleton and her eyes were huge with terror and popping out of her face.”[xlvii] This is probably why most accounts suggest she was on amphetamines towards the end, but note that he had described her at that reading as being “bony.” (It ought to be noted though that her autopsy showed her being 5’8 and 120 pounds,[xlviii] which is not particularly skinny.)

Cassady took him aside and told him that she’d been this way for 48 hours. He went on:

She says she wrote out a list of all our names and all our sins, she says, and then tried to flush them down the toilet where she works, and the long list of paper stuck in the toilet and they had to send for some sanitation character to clean up the mess and she claims he wore a uniform and was a cop and took it with him to the police station and we're all going to be arrested. She's just nuts, that's all.[xlix]

Kerouac noticed scars on her arms and Cassady said, “She tried to slash her wrists with some old knife that doesn't cut right.”[l]

Cassady had to work that night, so he asked Kerouac to watch Jackson. Kerouac was understandably hesitant, seeing how disturbed she was. In fact, Al Hinkle, who was probably not the most considerate of individuals, had strongly suggested that Neal have her temporarily institutionalised for her own safety. But Kerouac was loyal to Neal and reluctantly agreed. He stayed with her for some hours, along with a group of musicians from downstairs. Kerouac reported their conversation in his novel:

"But you don't realize what this means!" she kept saying.

"Now they know everything about you."

"Who?"

"You."

"Me?"

"You, and [Ginsberg], and [Cassady], and that [Gary Snyder], all of you, and me. Everybody that hangs around The Place.[6] We're all going to be arrested tomorrow if not sooner." She looked at the door in sheer terror.

"Why'd you try to cut your arms like that? Isn't that a mean thing to do to yourself?"

"Because I don't want to live. I'm telling you there's going to be a big new revolution of police now."[li]

That last line sounds more like Kerouac than Jackson but of course he was writing this book two years later, recalling a long conversation and so he was mostly just trying to capture the gist of what she’d said.[7] She went on, telling him about the dangers of the police and Kerouac tried to reason with her but to no avail. She said:

The police are going to swoop down and arrest us all and not only that but we're all going to be questioned for weeks and weeks and maybe even years till they find out all the crimes and sins that have been committed, it's a network, it runs in every direction, finally they'll arrest everybody in North Beach and even everybody in Greenwich Village and then Paris and then finally they'll have everybody in jail, you don't know, it's only the beginning.[8]

[…]

Oh, they're going to destroy you, Ray, I can see it, they're going to fetch all the religious squares too and fix them good. It's only begun. It's all tied in with Russia though they won't say it ... and there's something I heard about the sun's rays and something about what happens while we're all asleep. Oh Ray the world will never be the same![lii]

Kerouac responded with some Buddhist wisdom, trying to tell her that “this life is just a dream”[liii] and that she should relax because we are all God. A Canadian student noted in her thesis on Kerouac’s novel: “One might ponder the wisdom of trying to convince a mentally disturbed woman that all reality was an illusion, but Kerouac evidently thought that if she would have listened, things would have been different.”[liv]

Eventually, the musicians left and Cassady returned home, allowing Kerouac to leave the Franklin apartment. He was relieved that Natalie had survived his watch but she had told him something that perhaps he had not believed when the words initially came from her mouth: “This is my last night on earth.”[lv]

When Neal Cassady slept, Natalie Jackson got out of bed and climbed to the roof of the building. She wandered across the rooftops of several buildings in a t-shirt and white bathrobe. She either broke a skylight or found a broken one and used the glass to cut herself again. This time she cut her throat and she may have cut her wrists some more or perhaps these wounds were from the first attempt. In any case, she was bleeding when Mrs. A. L. Green, at nearby 1127 O’Farrell Street, saw her and called the police. (She also enlisted her husband’s help in rounding up several nearby roofers, according to one account.[lvi])

Jackson’s death was quite different from all the accounts in all the books that mention it. By the time the police arrived (25 minutes after the phone call), she had descended to the third floor of a fire escape at 1045 Franklin. (Note: This is the building next door to where she had spoken to Kerouac and lain in bed with Cassady—something almost every account has gotten wrong, claiming that she jumped from the roof of her own building.) An officer named Dick Wader attempted to get her attention while another, called Bob O’Rourke, entered the vacant apartment on whose fire escape she was now standing. When O’Rourke reached the fire escape, Jackson was already hanging from it. He stepped onto the landing to grab hold of her and managed to get a hand on her forearm, but he held her for no more than three seconds. She dropped from his grip, falling three storeys to the ground and leaving O’Rourke with her robe in his hand.

She had supposedly been hanging on for several minutes but it’s not clear exactly how or why she came to be in that position. Certainly, she was not in a stable state of mind. The multiple slashes on her wrists and throat suggest that she had gone back and forth between suicide and a desire to live. Perhaps she had jumped and then decided against it. Perhaps in her paranoid terror she thought the police were trying to arrest her rather than save her, and so she had tried to lower herself to a lower level. Alas, we will never know.

Jackson did not die on impact but rather passed away at Central Emergency Hospital from wounds sustained during the fall. She had suffered a fractured skull among various other traumatic injuries. She had no identification and so she was registered as Jane Doe, with the assumption being that she was almost a decade older than she actually was. An autopsy would later show that she had neither alcohol nor drugs in her blood.[lvii]

The police searched the area for anyone who might know her but no one came forward until Cassady—who had initially fled the scene upon finding she was dead—finally did the right thing and went to identify her body. He did not tell the police the truth, of course, but said he had known her a little due to living in the same building and that she had mentioned having some problems but had not said what exactly those were.

Jackson’s mother Irene flew from New Jersey and a funeral was held but none of the people who had known her in San Francisco attended. Instead, on December 11 a memorial was held and attended by Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Sheila Williams, and Locke McCorkle. Robert LaVigne was there, too, and sketched the attendees. It was titled “Dirge for Natalie Jackson.”[lviii]

The Impact of Her Death

The autumn of 1955 was an important moment in Beat and San Franciscan history, in no small part due to the 6 Gallery reading. It was a time of new friendships and artistic creation. It was the birth of the San Francisco Renaissance and the time when the Beat Generation—begun a little over ten years earlier on the other side of the country—finally started to gain some momentum. Ginsberg, Kerouac, Snyder, and their friends were enjoying a period of joy and excitement… and it came to a sudden end with this tragic, violent death.

In those days, news spread a little slower than today but already by December 1 Natalie’s death was in the newspapers. That’s how Carolyn Cassady found out. She guessed the “attractive, unidentified woman”[lix] who had supposedly leapt to her death was the same woman that had stolen her husband. The newspaper report was accompanied by a diagram showing Natalie’s movements prior to her death and the path her body took before hitting the street just in front of the building’s front door and behind a car that looked very much like her husband’s Packard. Soon after, the phone rang: “Carolyn... Natalie. Natalie’s dead.”[lx]

Carolyn said, “I saw the paper, Neal. I’m so sorry. Do you want to come home for a while?” He was soon back home, explaining that he had run out the back of the house just in case he was dragged into the story of her death, something he said might hurt Carolyn and the kids. Carolyn asked if Natalie had killed herself:

I don’t know. Partially—no, I don’t want to believe that—but she had become completely paranoid the past couple of weeks. She had an obsession about cops. Part of it was feeling so guilty about forging your signature—she’s been agonizing ever since—and she did that for me. I kept telling her it was all right and that you weren't mad, but it didn’t help. She got so bad, she talked about nothing but sin and guilt and how we were going to be arrested for our sins. Last week she tried to cut her wrists, but with a dull knife, and I told her all about suicide and not to think of it again. I thought she was better—in fact, she was her old self last night, and we’d talked a long time. I’ll never know if she really cut her throat on purpose. One paper said she fell on the skylight and could have done it that way. And she didn’t actually jump—she was so afraid of the cop, when he grabbed for her she must have backed up and off…[lxi]

It was a strange response. Neal likely did not want to believe she had ended her own life because that would mean she had done it due to his actions.

Is there any credence to that? Could it be that a woman who had slashed her wrists one day and then several days later slashed her throat whilst wandering semi-naked on a rooftop before plunging to her death had died by anything other than suicide? Certainly, she was hanging from a fire escape just before her death, so there was a degree of uncertainty. Brenda Knight told Jonah Raskin that “[t]he fact that she cut her wrists doesn’t mean she had suicidal tendencies. To me the wrist cutting was a big ‘fuck you.’”[lxii] She said “Natalie’s death could just as well have been an accident as a suicide.”[lxiii] Perhaps she is right but all the evidence points another direction, which is that Natalie was suicidal yet perhaps understandably scared of her own impending death.

In any case, her death prompted the following rather cold discussion in the Cassady household:

“But look, Neal, maybe it was an out for her, do you think? Maybe it was a chance for her to change her course—start over. She seemed to have boxed herself in. It could be a merciful release, couldn’t it?” Neal brightened a trifle. “Yeah, I suppose it really is better for her. She was insane—I couldn’t help her.”[lxiv]

As was so often the case with the Beat Generation, a woman’s tragic fate and terrible suffering were brushed aside and everyone just moved on…

Of course, that’s a little unfair because the people left behind suffered too. Kerouac was badly shaken by Natalie’s death. He moved back east just a few weeks later. John Suiter, author of Poets on the Peaks, suggests that Natalie’s death prompted him to write Visions of Gerard.[lxv] The timing certainly makes sense but it is impossible to say he wouldn’t otherwise have come around to writing that important story.

Although Carolyn’s recollection above suggests that Neal more or less snapped out of his depression, he was certainly hurt by Natalie’s death and even contemplated suicide himself, planning to make it look like an accident so that his family would receive compensation. LuAnn Henderson, a former girlfriend and a character in On the Road, tells a story that directly contradicts Carolyn’s account. She claims Neal went to stay with her for several weeks after Natalie’s death and that they spent two whole days together with Neal just talking, trying partially to excuse himself from the blame.[9] She believes the event changed him permanently, saying:

After Natalie’s death, it seemed like the girls he was being drawn to were the ones that really leaned on him—because he felt he’d really let Natalie down so badly, and he was somehow trying to make it up by helping other girls who were troubled in a similar way.[lxvi]

It did not change completely, though. For one thing, he continued his idiotic gambling system. Carolyn recalled:

Neal’s obsession with the races continued to grow, and now he insisted that he had to continue the system in order to atone for the guilt of having lost our savings and for Natalie’s death. He turned a deaf ear to reason. Every evening he spent an hour studying the newspaper race results, calculating every race and noting exact scores with hieroglyphics in the margins. Then, folding the sheet meticulously with the chart uppermost, he’d place it carefully, in order, in a beer carton and replace the carton on the closet shelf. I'd sigh as I watched the cartons accumulate, wishing all that mental genius and concentration were being directed toward some more constructive end. Jack agreed but said little.[lxvii]

This is consistent with a letter Neal wrote in 1958, which shows that he had not absolved himself of guilt as Carolyn seems to suggest. To Father Harley Schmitt, he wrote:

I became involved with a younger most sensitive girl who, when the money was gone and apparently despairing because of disappointment in me, committed suicide by leaping off the roof while I slept on in lazy indifference below.[lxviii]

It was December 2 when the rest of the Beat group found out about Natalie’s death. Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg borrowed Walter Lehrman’s car and picked up Bern Porter and Philip Whalen, planning to visit Kenneth Rexroth.[10] (It was a Friday night in San Francisco and Rexroth’s home was the place to be.) However, when they stopped at 1010 Montgomery Street, where Peter Orlovsky lived, Peter’s brother Lafcadio came to the door and broke the news. “You won't see Natalie any more, she killed herself,” he said.[lxix]

Snyder wrote in his journal:

Neal in bed, Natalie all night sitting by the stove smoking butts with the heat full on. Neal, after two nights up, sleeping, waking fitfully to watch her, sleeping again. […] & then she went up the fire-escape, wearing her red robe, perhaps to kill herself, perhaps to watch the roofers. There she broke a skylight & with the broken glass cut her throat—bleeding all down her front, the cops came, Natalie fell, fled, the cop grabbed at her, got her robe, & her body went down to the pavement & was from there ambulanced away. She died on the way to the hospital. Before she died she wrote a long list of people's names & across from each name, what vice they had.[lxx]

It sounds as though he learned this from a mixture of newspaper reports and information passed along from Cassady.

Ginsberg told Snyder: “the lesson from Natalie's death is that that we must be kind to people,” and Snyder—who at that time happened to be reading about mental health, a fairly uncommon term at that time—replied: “the lesson is that we must pay more attention to people with real psychological problems.”[lxxi] He noted in his journal: “Natalie was a lovely young girl, bugged no doubt […] Now she wanders the BARDO THODOL afraid of her own images.”[lxxii] He finished that entry with the short poem that headed this piece.

Ginsberg also wrote a short poem about Natalie, though his was more substantial. In it, he noted not just his sadness but a sense of guilt. He wrote:

Should I have invited you to Berkeley?

Given you money?[11] or more love?

or a rest home in my crazy lovely garden?[lxxii]

Later in the poem, he says “I ignored you.” It is a quite beautiful poem that Jonah Raskin has noted perhaps was continued later in Kaddish. I would have to agree that there are some similarities, not just in the lament for a dead “crazy” woman but in the language. There is also some linguistic connection between this and “Howl” and Ginsberg later eulogised her in “The Names II,” which was once considered a part of “Howl.” There, he wrote:

Natalie redhaired in bathrobe on the roof listing sinners' names for Government, police scared her to fire escape, her body on the pavement in the newspapers[lxxiv]

In fact, Natalie’s memory stayed with Ginsberg a long time. She frequently appeared in his dreams alongside other dead friends, including Joan Vollmer. Importantly, these were not bit players in his life—these were important friends and people he truly admired. He was scarred by these deaths and inspired to live and to create.

Kerouac would go on to immortalise Natalie as Rosie Buchanan in The Dharma Bums. Initially, he wanted the novel to open with the 6 Gallery reading, where we would find Natalie in Neal’s arms, happily watching the literary event of the century… and then he would close it with her tragic death. However, he changed this after the beatnik hysteria that followed On the Road. There was no need to sensationalise her sad, lonely death and at the same time feed the vicious media that was already attempting to connect a number of suicides and murders to the latest cultural fad. Instead, her death was tucked away in the middle of the book.

Conclusion

I hope that this essay has provided some more insight into both the life and death of Natalie Jackson. As I said at the beginning, it failed in its initial purpose of uncovering meaningful details of her life, but it has succeeded in presenting more about the final year of her short life than was previously known, and the details of her death are finally presented with a degree of accuracy. As always, I have tried to show where I was uncertain rather than spin an entertaining tale.

I do hope that more details emerge concerning the life of Natalie Jackson though I suspect as her life recedes into the past that is unlikely. The more I learned about her, the more interesting she seemed and the more frustrating it was that the details of her life eluded me. I would love to read her work or learn about her life in New York, for example. Ah well, maybe this humble effort of mine will inspire someone with more resources to dig into the archives and find something else…

A Silly Final Detail

In attempting to research the life of Natalie Jackson, I came upon the following quote, which is utterly meaningless but I think will be of interest to the Beat community. In 1940, a newspaper published a strange and random article that mentioned a woman called Natalie Jackson. Given that our Natalie Jackson would have been 9 years old at the time, it is certainly not about her, but the following line caught my eye:

It makes a guy feel awfully mad… to be snubbed by a girl who’s beat and sad… It’s been done befo’… we all do kno’… but chicks like that should take it slo’.[lxxv]

The use of “beat” here actually prefigures the Beats’ use of the word by five years. (You can read about the first written instance here.) It also predates crappy beatnik poetry by about 18 years. And of course, one can hardly wonder whether poor Natalie ought to have “taken it slo’” rather than get caught up in the destructive embrace of sociopathic Neal Cassady, whose fast life hurt many and brought him to his own early death in 1968.

Notes on Sources

I relied heavily on archival data for this essay: Allen Ginsberg’s and Gary Snyder’s journals, the various Beat letter collections, government records related to housing, and newspaper articles. Most accounts of this part of Beat history were sadly the result of lazy reporting wherein a handful of facts were cobbled together for a bit of colour. Assumptions were made and very obviously false details repeated. The only good account was by Jonah Raskin and sadly that was taken offline long ago. It contained a few small errors but had much that was true and involved a depth of research that was very impressive.

My sources are listed below. Due to this being published on Substack (our first long post here!), I can only hope that these are easy to use. If I have made any mistakes, please reach out and let me know.

Footnotes

[1] His name is always capitalised “Du Peru” or “DuPeru” in books about the Beats but historical records, including census and housing data, as well as what appears to be his signature on a draft card, indicate that the above (“Duperu”) is correct. It probably originated in the French “Duperreux.”

[2] Unfortunately, Ginsberg’s rushed journal notes are unclear and interpreting them requires some effort. He was in a strange and damaged mental space at the time and was also engaged in a frenzied social life, at the same time trying to pay bills and make a breakthrough as a poet. Thus, although he references Natalie quite often, it is not always clear what he means. In terms of chronology and detail, most other sources seem to draw upon these notes and reflect those authors’ interpretations of Ginsberg’s journals and so establishing a timeline is tricky.

[3] This appeared in Counter Culture Magazine about a decade ago. You can find it via the Internet Archive but the website itself is no longer online.

[4] It is possible, however. Cassady had promised Kerouac a free rail pass but this never came about because he’d given it to Jackson instead.

[5] It should go without saying that a novel is not the best of sources, but much of what he wrote in that particular book has been confirmed as accurate by people who witnessed the events depicted and so hopefully he has been fairly faithful here, too. In any case, we have no other sources until she made her suicide attempt later that night.

[6] The Place was a real San Francisco bar that attracted hipsters. It had poetry readings, showed art on the wall, and even the toilets were scrawled with poetic graffiti. It was the hangout of Beats, painters, and Black Mountain poets.

[7] He has a very abbreviated version of their interaction in Some of the Dharma: “I tried to tell her everything was empty, including her paranoic idea that the cops were after her & all of us—she said O YOU DON’T KNOW!” [p.346]

[8] I wonder to what extent this was Kerouac’s commentary on the beatnik crackdowns that were going on in San Francisco at the time he wrote his book…

[9] This may be explained by faulty memories. If Natalie died on the morning of November 30 and Neal called Carolyn on December 1, then there is a period of about 24 hours during which he might have been with LuAnn. It is possible that he was with her intermittently over the next few weeks.

[10] Lehrman took a number of famous photos of the Beat writers during this period and Bern Porter was an important figure in local publishing. One of them is here on the Beat Museum website.

[11] This seems to relate to a journal note: “secretly I betray; so was Natalie killed, I never gave them money.” As usual, it’s cryptic but suggests guilt at not lending Neal and Natalie money when they needed it. [Mid-Fifties, p.206]

Endnotes

[i] Raskin, Jonah, Counterculture Mag, “Wild Ones: Natalie Jackson (1931-1955) & The Usual Suspects: Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky & Robert LaVigne”

[ii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[iii] Kerouac, Jack, The Dharma Bums (Penguin: New York, 1976), p.15

[iv] Morgan and Stanford, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters (Viking: New York, 2010), p.255

[v] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.254

[vi] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.254

[vii] Ginsberg, Allen, Journals Mid-Fifties: 1954-1958 (Viking: London, 1995), p.73

[viii] Cassady, Neal, Grace Beats Karma: Letters from Prison 1958-60 (Blast Books: New York, 1993), p.14

[ix] Ginsberg, Allen, Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952-1995 (Perennial: New York, 2001), p.440

[x] Dharma Bums, p.15

[xi] Mid-Fifties, p.105

[xii] Gary Snyder Archives, Box 84, Folder 2

[xiii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[xiv] Dharma Bums, p.15

[xv] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.285

[xvi] Cassady, Carolyn, Off the Road: My Years with Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg (Penguin: New York, 1991), p.261

[xvii] Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, p.255

[xviii] Mid-Fifties, p.104

[xix] Mid-Fifties, p.107

[xx] Moor, Dave, Neal Cassady Collected Letters (Penguin: New York, 2004)

[xxi] Mid-Fifties, p.120

[xxii] Mid-Fifties, p.108

[xxiii] Mid-Fifties, p.121

[xxiv] Mid-Fifties, p.120

[xxv] Kerouac, Jack, Desolation Angels (Perigee: New York, 1980), p.127

[xxvi] Off the Road, p.261

[xxvii] Mid-Fifties, p.142

[xxviii] Collected Letters and Off the Road, p.258

[xxix] Collected Letters and Off the Road, p.259

[xxx] Off the Road, p.259

[xxxi] Off the Road, p.261

[xxxii] Ginsberg, Allen, South American Journals: January-July 1 960 (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2019), p.216

[xxxiii] Deliberate Prose, p.509

[xxxiv] South American Journals, p.216

[xxxv] Nicosia, Gerald, Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1994), p.469

[xxxvi] Off the Road, p.363

[xxxvii] Knight, Brenda, Women of the Beat Generation: The Writers, Artists and Muses at the Heart of a Revolution (MJF Books: New York, 2000), p.311

[xxxviii] Dharma Bums, p.15-16

[xxxix] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[xl] Los Gatos Times-Saratoga Observer Dec 1

[xli] Oakland Tribune Dec 1

[xlii] Off the Road, p.269

[xliii] Memory Babe, p.491

[xliv] Burroughs, William S., The Letters of William S. Burroughs 1945–1959, p.294

[xlv] Off the Road, p.270

[xlvi] Off the Road, p.270-271

[xlvii] Dharma Bums, p.109

[xlviii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[xlix] Dharma Bums, p.109

[l] Dharma Bums, p.109

[li] Dharma Bums, p.110

[lii] Dharma Bums, p.111

[liii] Dharma Bums, p.111

[liv] “Jack Kerouac: Dharma Voyeur” by Joanne Lee Wotypka (1999) found at https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/Voyeur.pdf

[lv] Dharma Bums, p.112

[lvi] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[lvii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[lviii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[lix] SF Examiner, Dec 1

[lx] Off the Road, p.273

[lxi] Off the Road, p.274

[lxii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[lxiii] Raskin, “Wild Ones”

[lxiv] Off the Road, p.274

[lxv] Suiter, John, Poets on the Peaks: Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen & Jack Kerouac in the North Cascades (Counterpoint: Washington D.C., 2002), p.178

[lxvi] Nicosia, Gerald, One and Only: The Untold Story of On the Road and LuAnne Henderson, the Woman Who Started Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady on Their Journey (Viva Editions: Berkeley, 2011), p.146

[lxvii] Off the Road, p.275

[lxviii] Sandison and Vickers, Neal Cassady: The Fast Life of a Beat Hero (Chicago Review Press: Chicago, 2006), p.244

[lxix] Gary Snyder Archives, Box 84, Folder 2

[lxx] Gary Snyder Archives, Box 84, Folder 2

[lxxi] Gary Snyder Archives, Box 84, Folder 2

[lxxii] Gary Snyder Archives, Box 84, Folder 2

[lxxiii] Mid-Fifties, p.208

[lxxiv] Ginsberg, Allen, Collected Poems 1947-1980 (Harper & Row: New York, 1984), p.261

[lxxv] The New York Age, Sept 7, 1940, p.10

Rather than edit this piece, as I'm not sure what effect that will have on the formatting of this essay, I will add here a quite interesting new discovery. I recently uncovered a letter from Ginsberg written in Sept 1955 that notes Natalie Jackson was present at the Friday-night salon at Rexroth's house where Ginsberg and Kerouac attended along with Snyder and Whalen. This was their first night hanging out together and was a very important moment in Beat history.

I couldn’t stop reading: well done. Thank you for writing it. It matters.