On the Road to Publication: Jack Kerouac and Joseph Heller

Notes on the anniversary of New World Writing 7, which featured excerpts from On the Road and Catch-22.

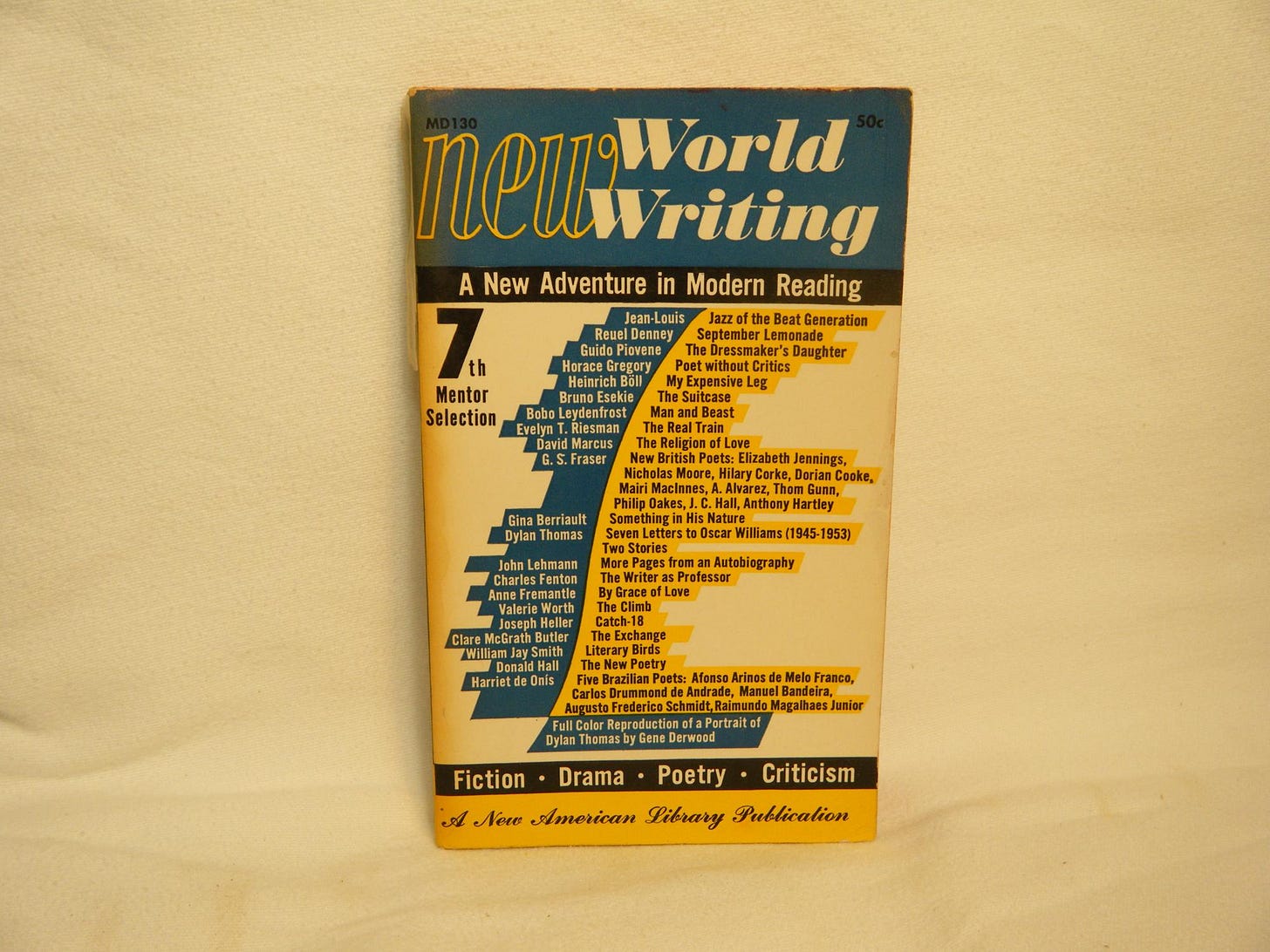

Seventy years ago, in April 1955, the seventh issue of a literary journal called New World Writing was published. Founded in 1951, the magazine had already attracted a number of successful writers and so the release of its seventh issue brought a reasonable amount of media attention.

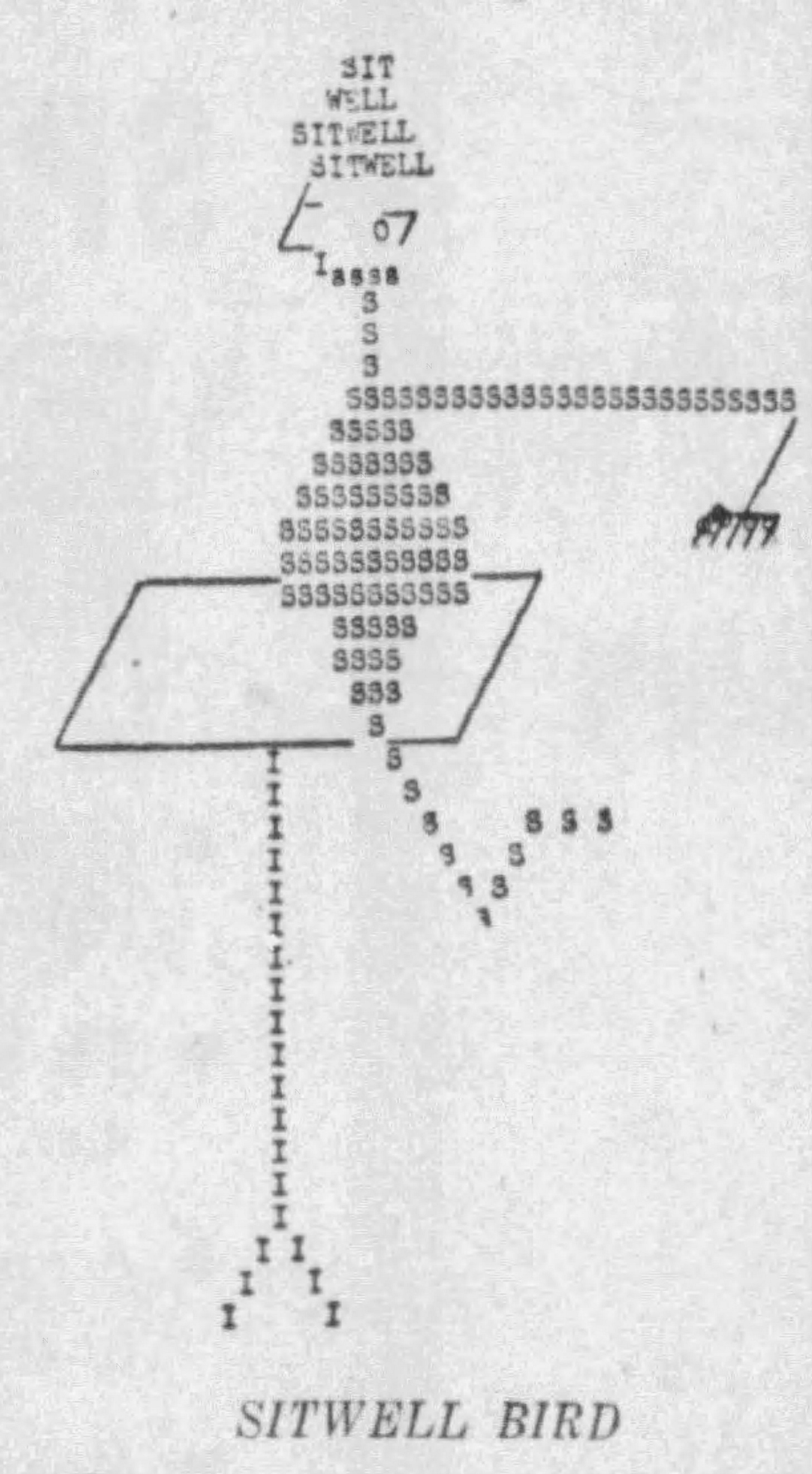

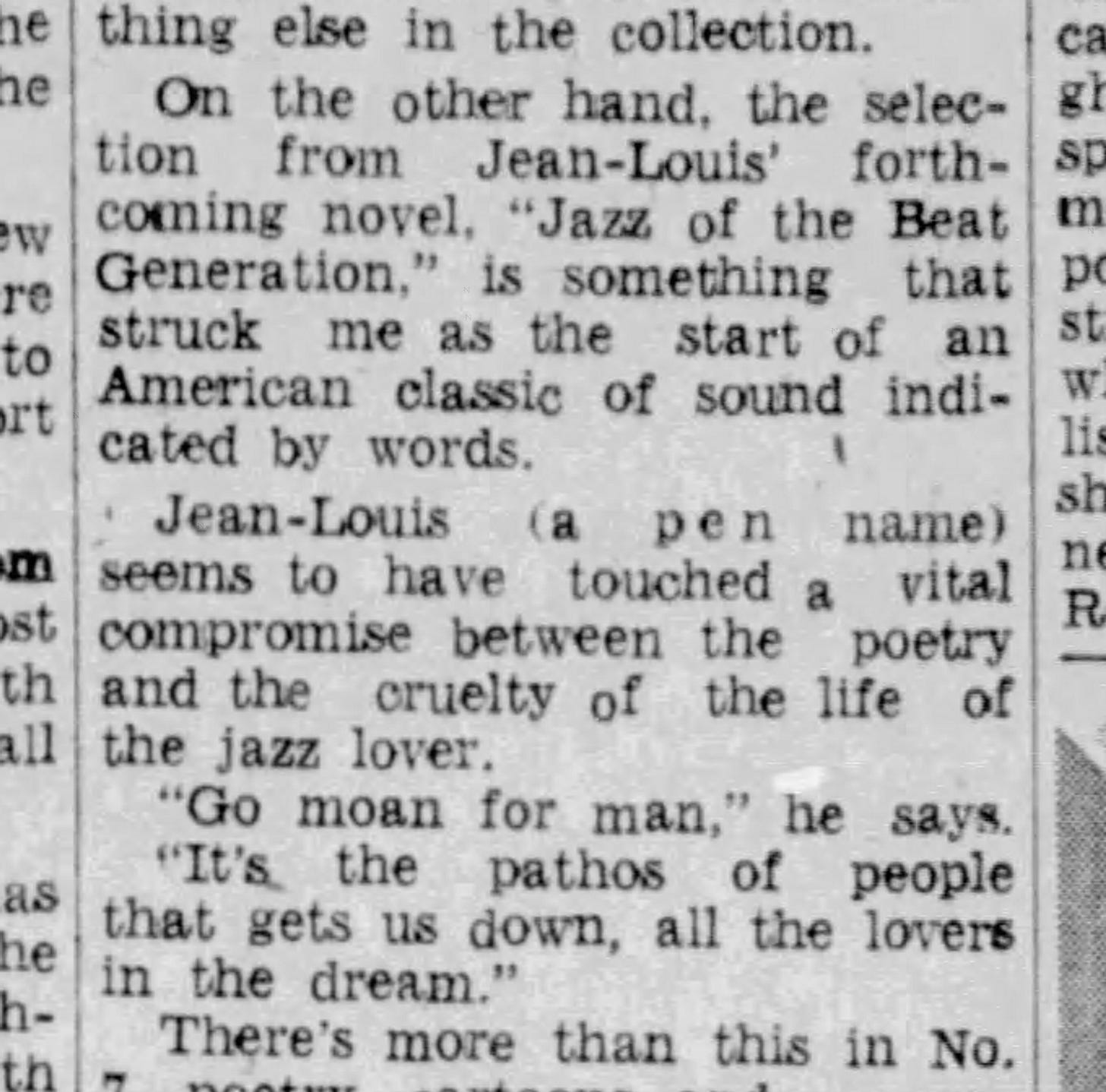

The big draw for this issue was a collection of material by the late Dylan Thomas (he had died in 1953), including two short stories and a collection of letters. One reviewer was also impressed by the “typewriter art” at the back, which was “fine fun”[i] even if not high art.[1] There were collections of poems by British and Brazilian poets and a total of 19 cartoons. It was, critics agreed, very much worth the $0.50 price tag.

Looking back from the 21st century, one is naturally drawn to two pieces of writing that most reviewers overlooked. These were excerpts from forthcoming novels that would prove to be among the most important of their era: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

Interestingly, neither of those novels had yet been given the title under which they would later be published. Heller’s story—the first chapter of an as-yet-unwritten novel—was titled “The Texan” and described as an excerpt from Catch-18, which is what he thought his book would be called. To avoid confusion with other Leon Uris's Mila 18, he changed it several times, eventually settling on Catch-22 for the book’s 1961 publication. (The film Ocean’s 11 in 1960 convinced him to change from Catch-11.)

Kerouac’s contribution to New World Writing 7 was called “Jazz of the Beat Generation” and his author biography showed what On the Road was intended to be titled as of early 1955:

This selection is from a novel-in-progress, THE BEAT GENERATION. Jean-Louis is the pseudonym of a young American writer of French-Canadian parentage. He is the author of one published novel.

One tends to think of excerpts as promoting forthcoming books but in Heller’s case the novel was not released for another six years and as for Kerouac, the excerpt was published under neither the same author’s name nor book title readers would later come to know. To the readers of New World Writing 7, he was simply “Jean-Louis.”

It’s a weird quirk of history that Kerouac and Heller came to share space in a literary magazine well before their best-known books were published, but there’s more to this story, at least in Kerouac’s case, and so let’s look at how and why “Jazz and the Beat Generation” came to be published.

Jazz of the Beat Generation

The story of the publication of On the Road has been told by a number of biographers and scholars, and it’s a complex tale that I suggest you read about in more depth.[2] For the purposes of this short essay, however, you should know that Kerouac’s novel The Town and the City had been published in 1950 and he had written a version of On the Road in 1951. The second book was much more experimental than the first and reflected his evolving approach to literature. For several years, he was eager to have it published, yet famously he was reluctant for it to be edited in any substantial way. Again, the textual history is complex and I suggest you find a more complete account but the gist of it is that Kerouac continued to revise his book but generally rejected the suggestions made by potential editors.

In early 1953, Kerouac met with Malcolm Cowley, an editor at Viking Press. Cowley was adamant that Kerouac’s work be edited to make it more easily accessible for the general public and Kerouac refused outright, causing Ginsberg—acting as his friend’s agent—to call him “a holy fool.”[ii] Later that same year, however, Cowley contacted Kerouac about the potential of publishing excerpts from On the Road in New World Writing. Kerouac replied:

When you hear from Arabelle [sic-Arabel] Porter [editor of NWW], if she wants any excerpts of mine, let me know and I'll act on that. I’m glad you’re trying to help me get published someplace now.[iii]

It had actually been Allen Ginsberg’s idea to send out short excerpts but in any case Cowley contacted Porter and in the middle of 1954 she agreed to publish “Jazz of the Beat Generation.” The excerpt took pieces from On the Road but, in Kerouac’s own words, there were “things from Visions of Neal sneaked in.”[iv] This referred to what readers will know as Visions of Cody, a much more experimental version of the story told in On the Road. Matt Theado, who likes to forensically dissect Kerouac’s text, says “the excerpt corresponds to approximately ten pages of On the Road and employs forty fewer commas.”[v] He mentions this in relation to the aforementioned disagreement between Kerouac and Cowley and suggests that “Jazz of the Beat Generation” may provide “readers an opportunity to see what the prose of the book may have looked like before Viking’s editing.”[vi]

Certainly, Kerouac was happy that Cowley had helped him publish at least part of his book. It was the summer of 1954 when Porter accepted “Jazz of the Beat Generation” and Kerouac wrote Cowley to express his gratitude:

This is the first, the only break into print for me outside of TOWN AND CITY. It gives me a lift towards further effort; I’d begun to lose heart.[vii]

Indeed, The Town and the City had been published four years earlier and since then Kerouac had been writing and innovating obsessively but without publication. This news lifted his spirits and also provided him with some cash. He was paid $120, which equated to $108 after his agent’s fee. (That’s about $1,300 today.)

Soon after, Kerouac wrote to Ginsberg. The following shows that Kerouac was not only uncertain of the title of his book but also how he wanted to be known as the author:

Lissen. Arabelle [sic-Arabel] Porter of New World Writing accepted the Jazz Excerpts that I had prepared from Sal Paradise and Visions of Neal, wild stuff. […] and now my mother says ‘Dont bodder with all that stuff,” meaning the New World Writing asking for my biography, she says “Call yourself just Jean-Louis.” I agree with her. It would be nice to be just Jean-Louis and not be bothered by anybody. “‘Jean-Louis is the christened name of an American author who prefers to remain anonymous because he wants to write.” Or what, what should I say, if anything at all? ‘Jean-Louis is an American author, 32 years old. The present selection is from an early novel completed 1951, THE BEAT GENERATION.” How’s that? I really mean it, would like to be anonymous like Wm. Lee [Burroughs] and go around secretly enjoying world.

The Town and the City had been published under the name John Kerouac and On the Road would be by Jack Kerouac, but this work was attributed to Jean-Louis.[3] To his agent, Sterling Lord, he explained:

after long thought I’ve decided to use my christened name Jean-Louis as nom de plume because of the intensely personal and directly autobiographical, non-fictional character of the work that I’ve been doing and want to go on doing. I need freedom to write without hindrance. In the appearance in New World Writing naturally I dont want a biography to give away the identity.

Later that year, Kerouac was sued for child support by Joan Haverty, which gave him another reason to conceal his identity. If his name appeared in the papers, she might have realised he had received a big cheque and tried to claim it.

In early 1955, Kerouac wrote to Lord expressing his belief that having “Jazz of the Beat Generation” in New World Writing would lead to the book finally being published. Over that year, he kept pushing further with his writing, whilst also having experiences that he would later write down, and eventually, towards the end of the year, he made headway with Cowley, who convinced him to change the title from The Beat Generation to On the Road and finally convinced Viking to offer him a contract. It had been five years since he began writing it and it would be another two years before it was published.

The publication of On the Road was one of the most significant moments in mid-20th-century literature. The fact that the novel was published by a major press and therefore widely distributed and reviewed was not only due to the book’s merits. Indeed, a great many publishers had passed on it, including Viking, due to it being so unconventional. Kerouac owed a great deal to the efforts of Ginsberg, Cowley, and Lord, each of whom had helped him tremendously. But he also succeeded by believing in his own work and refusing to compromise. His book could have been published years earlier if he’d been willing to make significant changes, essentially creating a watered-down version that sold out his artistic vision.

There are similarities with Joseph Heller and his inclusion in New World Writing 7. I am no expert on Heller and in fact have not read Catch-22 for at least a decade, but his biographies and interviews show that having a story in this issue of this journal played a major role in his career as a writer. This is from Just One Catch: A Biography of Joseph Heller:

Joe had known his literary models—especially [Louis-Ferdinand] Céline—were never popular. He began to fear his little experiment could not breathe in the marketplace. But then, one day, [his agent, Candidad] Donadio received a phone call from Arabel Porter, the executive editor of the biannual literary anthology New World Writing. […] She raved about Joe Heller. “Candida, this is completely wonderful, true genius,” she said. “I’m buying it.”

His confidence buoyed, Joe began to plan a second chapter.[viii]

As with Kerouac and On the Road, there are some uncertainties and myths but it seems most experts on Heller’s work agree that his inclusion in New World Writing sparked the writing of his most famous book. Unlike Kerouac, he hadn’t written his book yet, but that prestigious publication gave him the confidence to write it.

We can see then that there were a number of connections between these two authors. They were both published in New World Writing 7, their excerpts helped them in the process of publishing their most famous work, they were both fans of Céline, they both changed the title of their book quite frequently, and they both published their book about six years after first starting it. Those are just a few scattered thoughts…

Finally, I wish I knew more about Arabel Porter, who evidently had the prescience to see two great but unknown writers, to publish the first fragments of the most important novels of that era. In Subterranean Kerouac, Ellis Amburn calls her Kerouac’s “sole champion beside Cowley.”[ix] It is perhaps an exaggeration given the efforts of Ginsberg and Lord, but certainly her editorial eye helped in some way with the publication of two great novels.

A Final Note

I only realised the significance of this magazine and the fact that it was approaching its 70th anniversary because I was researching my book on the 6 Gallery reading, which naturally brought up certain meetings between Kenneth Rexroth, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, and Jack Kerouac.

As we have seen, and as is known to most fans of the Beat Generation, Ginsberg sometimes played the role of literary agent for his friends, and even when not in a professional capacity, he frequently promoted them. After moving to San Francisco in 1954, he got to know Rexroth, who was the most influential poet in the area. According to Ginsberg, Rexroth was very enthusiastic about Kerouac’s writing and positively reviewed it on his K.P.F.A. radio show. Ginsberg said that Rexroth compared Kerouac to Céline. However, he also admitted not listening to the show and that he merely “heard about it.” It is impossible now to verify what Rexroth said as there are no recordings from that period.

Later, Kerouac met Snyder for the first time just before a trip to Rexroth’s house. At Rexroth’s home, which functioned as a meeting place for writers on Friday nights, Kerouac read from “October in the Railroad Earth.” Snyder listened to the cadence and felt it was familiar. “I flashed that he was Jean-Louis,” Snyder recalled. “And then I knew he was a truly gifted writer with a new kind of language sense that would change how we wrote prose.”[x]

Indeed, 1955 was a hell of a year for the Beat writers. They were all making big breakthroughs and forging friendships that would expand and further the movement known as the Beat Generation.

Footnotes

[1] I recently enjoyed this short video on Substack, which shows how typewriters can be used to produce visual art.

[2] There are many good sources. I like Matt Theado’s Understanding Jack Kerouac. Another good account is Memory Babe by Gerald Nicosia.

[3] This short article goes into more detail about Kerouac’s various names.

Endnotes

[i] Dayton Daily News, April 17, 1955

[ii] Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, p.397

[iii] Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, p.402

[iv] Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, p.433

[v] Understanding Jack Kerouac, p.57

[vi] Understanding Jack Kerouac, p.56

[vii] Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, p.429

[viii] Just One Catch, p.177

[ix] Subterranean Kerouac, p.195

[x] Poets on the Peaks, p.147

Jack Kerouac believed in the merits of his own work. You wove an interesting story on the road to publication.

This excerpt, 'Jazz of the Beat Generation', wasn't reprinted until Ann Charters included it in The Portable Jack Kerouac in 2007.