Uncovering the Origins of “Gonzo” on the 20th Anniversary of Hunter S. Thompson’s Death

A detailed investigation turns up new evidence in a 55-year-old literary mystery.

Hunter S. Thompson died 20 years ago today. For months, I have thought about what to write for this occasion as it seemed necessary to mark it in some way, but everything I thought of writing seemed so bleak. This is an anniversary of a suicide, so perhaps “bleak” is the right tone but I believe in marking these occasions with a little more positivity. Thus, articles about why he killed himself, how he has been failed by the incompetence of those in charge of his literary estate, and what he would have made of the world today seemed a little too depressing.

But what about something celebratory? What about a tribute to a life lived to the full? What about a celebration of his greatest achievements? Everything positive I wanted to say was already in my book, High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism, and I didn’t want to repeat myself. (I’ve done that in a number of essays and articles about Thompson.) Eventually, I realised that I had not said everything I wanted to. There was one question that bugged me throughout the research and writing of my book. Perhaps solving a mystery—one that has puzzled people for about fifty years—would be a fitting tribute.

I was spurred into action about a year ago when, completely out of the blue, someone from Thompson’s past got in contact and offered a valuable piece of information. It did not completely solve the mystery but it certainly changed how I looked at it and gave credence to the one theory I had previously dismissed outright. It also prompted me to dig even deeper in an attempt to finally answer this most tantalising question.

In my book, and in a handful of essays written around the time it was published, I explained pretty thoroughly what “Gonzo” meant (here is one example), but I was never fully able to explain where the word actually came from. Or to put it another way, I could easily tell you what Gonzo Journalism was and how the concept was invented and used, but the actual word “Gonzo” was shrouded in mystery. It’s something that everyone with an interest in Thompson’s work has a theory about, with some of them being more credible than others, but I’d never found one that was completely convincing.

In this essay, I am going to attempt to solve this mystery. Knowing that not everyone will come to this with the same starting knowledge, I will first give a brief explanation of how Hunter Thompson came to call his writing style “Gonzo” and then run through some of the leading theories. Towards the end, I will add several completely new pieces of evidence and then draw a conclusion. If you are already very familiar with Thompson’s biography, you may want to skip the first part as there is nothing particularly new there. If you are less familiar, it will give the necessary background for what follows. Here is an overview:

The Birth of Gonzo (explaining how HST adopted the term “Gonzo journalism”)

The Etymology of Gonzo #1: Thompson and Cardoso (a look at a few leading theories)

The Etymology of Gonzo #2: Brinkley and Booker (considering what is possibly the most widely accepted theory since 2007 alongside some new evidence)

Back to Boston: Accusations of Theft and a Visit from Baba Ram Dass (a look at something undiscovered until now)

Conclusions

For those of you who have read my recent writings on the Beat Generation, you can probably already guess this is going to be lengthy. I promise this is not pure self-indulgence and I don’t want to waste your valuable time, but I believe in presenting all angles of complex and misunderstood issues and explaining each part thoroughly but clearly in order to allow the reader to make an educated decision and I am fully aware that yours may differ from mine. Please feel free to leave—in civil terms, obviously—your dissenting opinion in the comment section.

The Birth of Gonzo

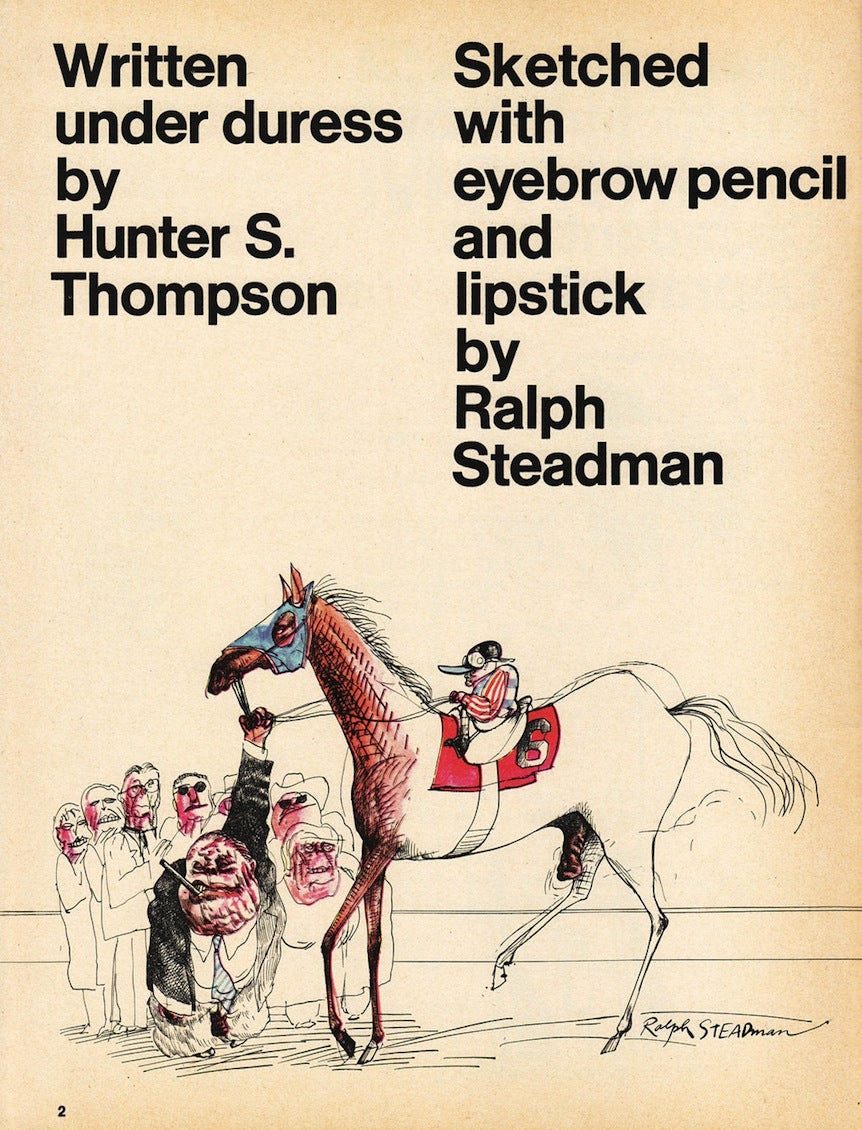

The concept of Gonzo journalism was born in 1970 at the Kentucky Derby, when Hunter S. Thompson and Ralph Steadman teamed up to cover a sporting event but instead turned to face the crowd and brutally caricatured them in a style so utterly original that it needed its own name.

This was not something that occurred spontaneously and without precedent as Thompson had been developing his own style of reporting for more than a decade by this point. He’d worked within the journalism industry but had always attempted to break the rules, starting in small ways and then pushing the boundaries further and further. By the late sixties, he was writing in a way that most major publications rejected because it was so unconventional. Inspired by Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell, he tended to put himself into the story and focus on characters, events, and dialogue rather than the bigger picture. He liked to use the techniques associated with fiction rather than journalism and began to eschew the idea of objectivity. Increasingly, he used humour and vitriol to attack those he disliked, and this was something he drastically increased following the events of 1968, which he viewed as the year when the American Dream finally died.

By 1969, Thompson had developed a style of writing that one could pick apart and say was a composite of techniques borrowed from the writers he most admired: Hemingway, Orwell, F. Scott Fitzgerald, J.P. Donleavy, H.L. Mencken, and Joseph Conrad. However, these disparate influences, combined in Thompson’s own mind amidst the late sixties acid culture and used almost as a weapon directed against institutional corruption, meant that he had created a wholly original form. That year, he wrote one of his finest essays: a story about the French skier Jean-Claude Kily. In it, Thompson was provocative, funny, and insightful. It was a long piece of writing and it embarked upon many strange digressions, but from start to end it was utterly engaging. Thompson had struggled to get a conventional story about this absurdly boring man, so he made his report about the process and put himself at the centre of the narrative, with his struggle guiding the reader rather than writing a traditional story about the skier.

“The Temptations of Jean-Claude Kily” was a milestone publication for Thompson but there was one last thing missing: spontaneity. This would be the final piece in the Gonzo arsenal and it would be added the following year, at the 1970 Kentucky Derby. The full story of Thompson’s coverage can be read here or in High White Notes, but the most important part is that after making his notes, he found it difficult to actually write the story and as his deadline came and went, he began desperately typing up some of his more coherent notes and sending them off to the editor, mostly just to placate him until Thompson could do some real writing. However, the editor (Warren Hinckle) thought the notes themselves were great and the article was published with these barely polished notes adding to the frantic immediacy of the story.[1]

At first, Thompson was embarrassed. For a decade, he had devoted himself to his craft. His writing was unconventional and he certainly knew how to goof around, but he laboured over each story because writing was for him of the utmost importance. Now, however, he felt he had violated his principles and potentially ruined his career. He wrote to a close friend, Bill Cardoso, editor of the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine:

It’s a shitty article, a classic of irresponsible journalism—but to get it done at all I had to be locked in a NY hotel room for 3 days with copyboys collecting each sheet out of the typewriter, as I wrote it, whipping it off on the telecopier to San Francisco where the printer was standing by on overtime. Horrible way to write anything.[i]

To Thompson’s great surprise, the article was a sensation and within weeks of its publication he was trying to get his agent to sell the movie rights. Most importantly, though, he received feedback from Cardoso, with whom he had become close friends in the late sixties. Cardoso was another writer (although mostly an editor) with a healthy interest in politics and drugs. When he read “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” in the first issue of Scanlan’s Monthly, he wrote to Thompson to say it was “pure gonzo” or “totally gonzo” (Thompson remembers the former; Cardoso says it was the latter) and Thompson almost immediately adopted this word as his personal brand.

It should be no surprise that Thompson immediately took to the word. Since childhood, he had been almost pathologically obsessed with the idea of himself as an outlaw and always sought to occupy his own category. When he had to work with others, he was the leader, the misfit, the rebel. Looking back over his early writing, comparing the original and published versions, one easily sees how Thompson was talented enough that his work was accepted yet heavily edited to make it suitable for those publications. He had a raw talent and an incredible work ethic, but he refused to adhere to the rules. Now, he was not just an outlaw journalist… he was a Gonzo journalist. He loved that this term set him apart from his peers and even when others attempted to group him as part of the New Journalism movement, he was adamant that he was in his own category—perhaps the only one-man literary genre of any importance.[2]

The word “Gonzo” began appearing in his letters in 1971, where he emphasised the immediacy of it:

This happens every time I leave the scene of a piece—physically and mentally—before actually writing it. So in terms of Gonzo Journalism (pure), Part One is the only chunk that qualifies—although even the final version is slightly bastardized. What I was trying to get at in this was [the] mind-warp/photo technique of instant journalism: One draft, written on the spot at top speed and basically un-revised, edited, chopped, larded, etc. for publication. Ideally, I’d like to walk away from a scene and mail my notebook to the editor, who will then carry it, un-touched, to the printer.[ii]

He used the word increasingly in private correspondence and then referred to it several times in his classic “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” first published in Rolling Stone at the end of 1971 and then as a book in 1972. He called that book “a failed experiment in Gonzo Journalism” as true Gonzo would have involved “buy[ing] a fat notebook and record[ing] the whole thing, as it happened, then send[ing] in the notebook for publication—without editing.”[iii] This was something he moved closer to with his coverage of the 1972 presidential campaign. By 1974, he was talking about Gonzo frequently in public through his interviews and speaking gigs and the term became fairly well known after that, appearing in various dictionaries in the 1980s.

This is all well documented in High White Notes, as well as William McKeen’s Outlaw Journalist and other books such as Timothy Denevi’s Freak Kingdom and Corey Seymour’s Gonzo. But even though we know the story of Gonzo’s creation, there is no consensus on where the word actually came from or what it meant before Thompson adopted it.

The Etymology of Gonzo #1: Thompson and Cardoso Explain

Hunter Thompson is on record many times as saying that his friend Bill Cardoso called his Kentucky Derby story “pure gonzo.” He repeated this in interviews quite frequently from 1974 onwards although the letter in which this phrase allegedly appeared has never been published. Although both men gave different accounts of the word’s origins, we can be fairly sure that “Gonzo journalism” came from this one letter. But where did Cardoso get the word from and what did it mean?

Thompson often spoke about the meaning of Gonzo as it applied to his writing and occasionally added bits of etymology. In 1977, for example, he told Peter Gzowski:

It’s an old Boston street word. It’s one of those Charles River things that started when you’re twelve years old on the banks of the Charles River. “Gonzo” is a word that Bill Cardoso, who’s an editor at the Boston Globe, came up with to describe some of my writing. I just liked it. And I thought, “Well, am I a new journalist? Am I a political journalist?” I’m a Gonzo journalist . . . And why not?[iv]

This is probably the most common definition: “an old Boston street word.” It certainly makes sense given that Cardoso was from Massachusetts. Born in 1937 (the same year as Thompson), he grew up in Cambridge and Somerville, then studied at Boston University and worked for the Boston Globe. One could reasonably assume then that “gonzo” was local slang.

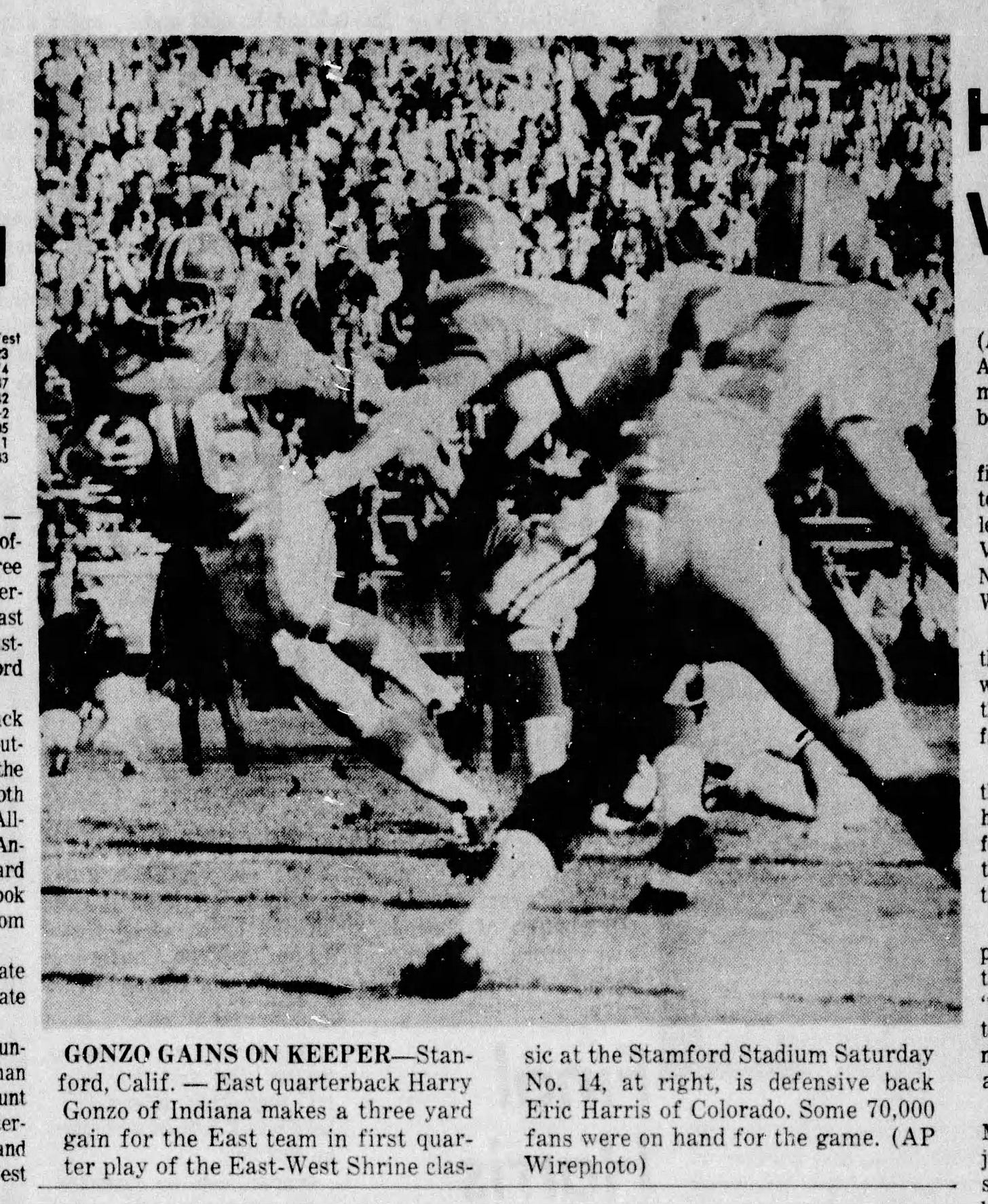

But is there any evidence to support this? A search of webpages, newspaper articles, and books certainly turns up thousands of assertions of “gonzo” being Boston slang… but all of them repeat Thompson’s claim and all of them come from after 1970 (except for two references that will be discussed in a later section). If we go back before 1970, which of course would have to have been when Cardoso learned this word, there is nothing. “Gonzo” exists as a name and as a word in Italian and Spanish (we’ll come back to that later) but there is nothing about it being a slang term and certainly not one used in Boston. In fact, if we search newspaper archives (which tend to include words that look like the intended one), there were 11,000 instances of the word “gonzo” appearing between 1900 and 1970 in the United States but only 36 came from Boston, and most of those refer to Indiana Hoosiers quarterback Harry Gonso, with his name spelled incorrectly.

Looking back through those archives, it does seem that “gonzo” had some kind of unclear meaning in the early thirties in the world of wrestling and boxing, but this was before Cardoso was born. For example, in 1930 a reporter wrote “Yet in his last two fights, widely separated, he whipped Johnny Farr and Jake Zeramby, neither of whom could be called a gonzo.”[v] It is certainly possible that the word stuck around and was, as Thompson suggested, a “street word” used in the area, but there really isn’t much to back that claim up because it appears in no other newspapers, magazines, journals, or books (except as someone’s name).

For his part, Cardoso was always evasive about the word, or if not evasive then misleading. One sometimes gets the feeling the two men were perhaps playing some kind of joke on interviewers (which is definitely a possibility). He told E. Jean Carroll, author of the controversial but valuable biography Hunter:

I think the word comes from the French Canadian. It’s a corruption of g-o-n-z-e-a-u-x. Which is French Canadian for “shining path.”[vi]

Later, he pushed this further, in a not-so-serious way:

Gonzo is of French Canadian origin, a corruption of gonzeaux, which is itself a corruption of the old Dominican Republic dandy inside-baseball phrase sendero luminoso, roughly meaning ‘Signify batsman electric to take two, then hit to right, sending the spheroid beyond your grandmother’s paisley shawl. That’s my claim, see, and I’m staking to it. But what the hell do I know?

For years, people seemed to accept Thompson’s account and then later, after Carroll’s book came out, the second version became common. (Many of the book’s reviewers quoted Cardoso as though the mystery had finally been solved.)

So now we have two apparently distinct accounts of the meaning of the word “Gonzo.” Thompson said it was Boston street slang and Cardoso said it was French Canadian. Of course, it is possible that both are true because of the influence of French Canadians in New England. The word “gonzeaux” certainly could have made its way across the border and into the streets of Boston. However, the word “gonzeaux” appears to be Cardoso’s own creation. Every single record of this word online is directly attributed to his explanation in Carroll’s book and a search of French-Canadian words yields nothing particularly close to the above except “gonze” and “gonzesse,” words meaning “man” and “woman” from the early 1800s. (This appears to be standard French as well as French-Canadian.)

If we are to stick with the idea that Cardoso heard the word on the streets of Boston, then it is definitely possible that it came not from French-Canadian but via another route. It clearly does not look like an English word and so it makes sense that it might have come from another language. Indeed, Italian dictionaries show it to have meant a number of unflattering things with all of them essentially boiling down to “a stupid person” (or, oddly enough, a Cockney). This dictionary from 1841 shows it to mean a “nincompoop”…

There is a suggestion also that it came from Spanish and certainly there were Italians and Spaniards on the streets of Boston, so this is technically possible, but the various online dictionaries that claim it derives from the Spanish “ganso,” meaning “goose,” are far from convincing.

Interestingly, in one interview, Thompson confidently said that the word had its origins in Portuguese. He said, "It's a Portuguese word. It means weird, off the wall, Hell's Angels would say. Out there. Gonzo, learning to fly as you're falling."[vii] However, there is once again little in the way of proof for this claim.

As we have seen, Thompson claimed the word “Gonzo” had been Boston slang… and Cardoso said it was French Canadian… and Thompson later contradicted himself to say it was Portuguese… Before we dig any deeper, it is probably worth mentioning the fact that both men had a propensity for screwing with people. They both had a mischievous sense of humour and a weird attitude towards truth and fiction, so I feel relatively confident in assuming that they were to some degree simply playing a joke on the reporters who asked them and the audience reading those publications. Thompson liked to tell stories about his life and deliberately engaged in obfuscation for unclear purposes so that his biographies—as interesting and well written as they are—tend to be filled with falsehoods. For one example, he told the Paris Review that the name Raoul Duke (his literary persona) came from Fidel Castro’s brother, but in fact he had found it in a newspaper. This is explained in more depth here. The fact that he said “I never did figure out what ‘gonzo’ meant. I still don’t know”[viii] in 1975 shows how inconsistent he could be, which further points to the idea that he did not want people to know the word’s true origins.

In this case, I think the claim about Gonzo being “a Portuguese word” supports my theory because Cardoso lived in the Azores (a Portuguese territory) in the early 1970s and supposedly had Portuguese ancestry. This is precisely Thompson’s humour sort of humour. By saying it’s “a Portuguese word,” he is subtly telling the reporter that it was simply Cardoso’s creation.

To confuse matters a little more, Thompson told High Times in 1977 that he had heard Cardoso use the word two years earlier than he normally claimed:

One of the letters came from Bill Cardozo [sic], who was the editor of the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine at the time. I’d heard him use the word Gonzo when I covered the New Hampshire primary in ’68 with him. It meant sort of “crazy,” “off-the-wall’’—a phrase that I always associate with Oakland. But Cardozo said something like, “Forget all the shit you’ve been writing, this is it; this is pure Gonzo. If this is a start, keep rolling.” Gonzo. Yeah, of course. That’s what I was doing all the time. Of course, I might be crazy.[ix]

This is interesting because although he still sticks with the story of Cardoso using “pure Gonzo” to describe the Kentucky Derby article, it suggests Cardoso had the word in his vocabulary several years before that, which of course backs up the theory of it being a “Boston street word” he’d known possibly from his youth. Thompson seems to suggest this in the following 1975 interview as well, although his wording makes it unclear when exactly he first heard the word and his definition of it is somewhat vague:

By this point, Thompson was famous and people frequently referred to him as a “Gonzo journalist,” so naturally reporters attempted to explain it and, with no other evidence available, they tended to put stock in Thompson’s accounts. To give one example, that same year, a Canadian journalist called it “a Boston word of obscure origin.”[x] Presumably it was “obscure” because no one had been able to verify the authenticity of the claims made by Thompson and Cardoso.

This has continued in the various Thompson biographies and a number of essays, as well as etymological websites and dictionaries. Thompson’s biographer, Peter O. Whitmer, citing the above High Times interview but giving no other source, expanded on Thompson’s definition to say Gonzo was “a term the South Boston Irish used to describe the guts and stamina of the last man left standing at the end of a marathon drinking bout.”[xi] It is a definition one commonly encounters online and certainly it does have a certain appeal, so I can see why people would want to believe it, but I have seen little in the way of evidence for it. McKeen repeated it in his excellent biography, Outlaw Journalist, but similarly did not offer a source. He then repeated the claim in his contribution to Fear and Loathing Worldwide:

Cardoso worked at the Boston Globe and gonzo was local bar slang. It was used to describe the last one standing after a night of heavy drinking. That person, it was recently said, was gonzo.[xii]

It might be true… but it sounds more like something we just want to be true. Hunter S. Thompson died on February 20, 2005 and Bill Cardoso passed away one year and one week later. Both of them had given statements on the word’s origin and meaning but both seemed to be joking, deliberately misleading people as some kind of lark. After Cardoso’s death, the San Francisco Chronicle said that “in interviews over the years, Mr. Cardoso was often sketchy about the word's origins” and this is true, so likely we will never know for sure.

But again, where did Cardoso get the word “Gonzo”? I’ve mentioned Harry Gonso already and certainly that quarterback was regularly in the news during Cardoso’s time as a newspaper editor (his name spelled “Gonzo”), so undoubtedly he was aware of this person. Given that Thompson took “Raoul Duke” from a newspaper article, perhaps he and Cardoso had seen headlines involving Harry Gonso and simply found the word amusing. Thompson was like that with words and much of the Gonzo lexis (atavistic, savage, doomed, etc.) can be traced to what he was reading just prior to the first written use of the term in his oeuvre. In other parts of the country, there were Japanese-Americans with “Gonzo” as part of their name, and in fact “Gonzo” does seem to have been a reasonably common name in the western half of the country. But why he would have taken this name and modified it is unclear… Besides, there are more compelling theories to explore.

The Etymology of Gonzo #2: Brinkley and Booker

From the mid-seventies until the release of E. Jean Carroll’s biography in 1993, people generally took Thompson at his word about “Gonzo” coming from the streets of Boston (with a few less-informed reporters believing it was created simply to be the name of a character in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas) and after that they tended to believe Cardoso about it working its way down from Quebec as “gonzeaux,” but in 2007, two years after Thompson’s death, another theory emerged.

In Corey Seymour’s oral biography, Gonzo, Douglas Brinkley, who was for a time Thompson’s literary executor, explained:

The Internet is full of bogus falsehoods propagated by uninformed English professors and pot-smoking fans about the etymological origins of “gonzo.” Here’s how it happened: The legendary New Orleans R&B piano player James Booker recorded an instrumental song called “Gonzo” in 1960. The term “gonzo” was Cajun slang that had floated around the French Quarter jazz scene for decades and meant, roughly, “to play unhinged.” The actual studio recording of “Gonzo” took place in Houston, and when Hunter first heard the song he went bonkers—especially for this wild flute part. From 1960 to 1969—until Herbie Mann recorded another flute triumph, “Battle Hymn of the Republic”—Booker’s “Gonzo” was Hunter’s favorite song.

When Nixon ran for president in 1968, Hunter had an assignment to cover him for Pageant and found himself holed up in a New Hampshire motel with a columnist from the Boston Globe Magazine named Bill Cardoso. Hunter had brought a cassette of Booker’s music and played “Gonzo” over, and over, and over—it drove Cardoso crazy, and that night, Cardoso jokingly derided Hunter as “the ‘Gonzo’ man.” Later, when Hunter sent Cardoso his Kentucky Derby piece, he got a note back saying something like, “Hunter, that was pure Gonzo journalism!” Cardoso claimed that the term was also used in Boston bars to mean “the last man standing,” but Hunter told me that he never really believed Cardoso on this. Just another example of “Cardoso bullshit,” he said.

It is an interesting theory and because it was provided by an apparently reputable source in a very popular book, it is widely seen as the right one. Since that book was published, this has probably been the leading theory on the origins of the word “Gonzo.” (Of course, we could push further and ask where Booker got the word from and some have indeed pursued that rabbit hole, but it is a little beyond the scope of this essay…)

I was sceptical, to be honest, for a number of reasons. Brinkley has a habit of making confident pronouncements about subjects he does not really know and due to his reputation as one of the great living historians, he is generally taken at his word. This explanation honestly smacked of bullshit largely because there is no record whatsoever of Thompson having an interest in that song or artist. He wrote a lot about music in the sixties and seventies and liked to share the songs and albums that he enjoyed, but in all his letters and articles and memos and audio tapes, he never once mentioned Booker or the song that supposedly he loved more than any other during that productive period of his life. This is more than a little suspicious. Thompson famously loved Bob Dylan’s “Mr Tambourine Man” and did not hesitate to broadcast his enjoyment of it. (He dedicated Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas “to Bob Dylan, for Mister Tambourine Man.”) In a letter, published in Fear and Loathing in America, he even wrote a list of the best ten albums of the sixties—the period during which he supposedly this was his favourite song—but Booker did not get a mention there or anywhere else. The fact that Booker is so completely absent and that so many other musicians are credited, particularly when coupled with other dubious claims made by Brinkley, made me dismiss this explanation outright.

(One other note on this topic is that the website WordOrigins.org claims: “The bit of it being Cajun slang or Louisiana jazz jargon is unsubstantiated. I have found no uses of the word in relation to Louisiana until the appearance of Booker’s tune in 1960.”[xiii] That doesn’t really impact our inquiry into where Thompson got the word, but it does show the historian once again confidently asserting something that seems to be untrue.)

Then, there is also the fact that Thompson said, in 1974, that when Cardoso called his writing “pure Gonzo,” it was the first time he’d ever heard the word.[xiv] As I’ve already mentioned, we cannot necessarily trust what Thompson said about his life because of his exaggeration, obfuscation, and outright mythologising, but we must at least entertain the possibility—in the absence of real evidence to the contrary—that he was telling the truth. That means, if he had in fact not heard the word “Gonzo” prior to 1970, then he could not have been obsessed with a song by that name for the entirety of the 1960s. However… whilst this seemingly corroborates my notion of Brinkley as a bullshitter, I cannot overlook the fact that Thompson at least twice claimed to have heard Cardoso use the word in 1968. Once of those was a throwaway comment that I don’t believe to be true, but it highlights the difficulty in pinning down the truth as it concerns the life of a man who seemed incapable of telling the truth.

For many years, then, I was very sceptical about Brinkley’s claim on the grounds that it had no evidence whatsoever to back it up. It was simply a historian saying “This is what a dead guy told me; you can’t disprove it.” There was admittedly a suggestion in McKeen’s 2008 biography, where he said that “Gonzo” was “[p]erhaps deriving from the French Canadian gonzeaux” but that “Cardoso used it in the Boston-bar derivation, referring to the last man standing after a night of drinking,” then oddly added “there was an old James Booker organ instrumental out of New Orleans that Hunter used to pick up on WWL late at night. ‘Gonzo’ had been a regional hit and Hunter had liked the demented, loopy tune from the first time he heard it.”[xv]

At least we have another person making this claim but McKeen does not mention any source in the notes section of his book. It was not mentioned in his earlier biography, which was based on extensive interviews with Thompson, and so one wonders if perhaps this claim came to McKeen via Brinkley. But then again, Brinkley seems to claim that Thompson had the record and blasted it annoyingly whilst McKeen seems to say that he occasionally heard it on late-night radio….

I have a hell of a lot more respect for McKeen than Brinkley but I was still far from convinced until early last year I received an e-mail from Thompson’s good friend, Paul Semonin. He had stumbled upon an article I had written about Thompson and that had led him to High White Notes. He wrote to congratulate me and also to add “an interesting footnote for you on the origins of [the word Gonzo] and Hunter’s exposure to it.” He explained:

In the early 1950s, when we were high school friends, I began to bring 45rpm R&B records to our high school dance parties, ones that I crossed the color line in Louisville to purchase at black music stores. I still have a small collection of those discs and years ago among them I found the tune by James Booker titled “Gonzo.” In his book, Bill McKeen mentions this song as a possible source, but he claims Hunter heard it on the New Orleans radio station late at night “and had liked the demented, loopy tune from the first time he heard it.” We were both listening to WWL in high school, however that record was not released until later in 1960. That’s the year Hunter and I lived together in Puerto Rico, and were together again in New York for a few months, before taking a drive-away car across the country to the West Coast in September. I don’t think I purchased that record in San Juan, but more likely got it in Harlem while we were in New York, then carried it with us on our trip across country. Although I can’t say for sure that Hunter picked up on the term then, it seems a likely possibility given the intense nature of our friendship at that time.[xvi]

I have read this e-mail many times and of course it does not provide definitive proof that Thompson had heard the song and certainly does not suggest that he listened to it obsessively over a period of a decade, but it does suggest that he knew of it. It tells us that more than likely Thompson heard Booker’s “Gonzo” in 1960 and may possibly have continued to listen to the song (whether with his own record or on the radio) over the next decade.

Back to Boston: Accusations of Theft and a Visit from Baba Ram Dass

We have looked at a number of theories so far and all of them have been to some extent mentioned in books and essays, but what comes next will probably be quite a surprise. Let us put the above ideas aside for a moment and consider the possibility that Bill Cardoso encountered the word “Gonzo” at some point shortly before writing his letter to Thompson.

A man named Charles Giuliano, who calls himself the “Original Gonzo Journalist,” has claimed several times to have coined the term “Gonzo” and says that Cardoso “stole the word” from him. More than that, he says he invented it entirely:

I coined the word just […] while telling an anecdote to friends gathered in the Commonwealth Avenue basement apartment of the late William J. Cardoso then the editor of the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine.

[…]

“What was that you said Charles? Gonzo! What does that mean?”

To which I responded “Gonzo, as in over the fence, out of the park, home run. Outah here. Total gonzo.”[xvii]

Obviously the veracity of this story is impossible to prove but it certainly is suspicious. In several places, Giuliano says he “coined” the word and that Cardoso “stole” it but he also admits saying to someone else in 1970, “It’s a new hip word that all the kids are using.”[xviii] So which is it? Did he coin it or was it already in use?

We will never know what exactly was said between Giuliano and Cardoso but Giuliano certainly used “gonzo” as an adjective in a published article on July 3, 1970. Oddly, despite calling Cardoso a friend and having shared with him a “new hip work that all the kids [were] using,” he said, “Suspecting that Cardoso was up to no good I slipped the word into my review.”[xix] To me, this is quite strange. I can’t imagine why he would have wanted to protect the word (which he says was already in common use) or why he would have suspected a friend of stealing it, but it is true this word appeared in an article he wrote in July and Thompson’s Kentucky Derby article was published in June, and as I’ve mentioned already, we simply don’t know when Cardoso wrote his letter to Thompson saying using the phrase “pure gonzo” (or “totally gonzo”).

Maybe Cardoso responded later, after seeing Giuliano’s article… Or maybe he used it after hearing Giuliano saying it… We cannot know for certain but I am far from convinced by Giuliano’s claim. He is adamant that he was the one who coined the term and that his friend stole it and he writes: “I defy anyone to produce an earlier printed use of Gonzo.”[xx] Well, challenge accepted, Mr. Giuliano! I have found quite a few examples, with it being a given name, a surname, an adjective, and a noun. It was also the name of a racehorse in 1960. Most written instances not only predate Giuliano’s alleged coining of the word but do so by decades. However, perhaps the most relevant one to post here is from just a few weeks earlier and published in the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine:

On June 14, 1970, in an article on Richard Alpert (better known as Baba Ram Dass), journalist Robert Taylor wrote that he “went Gonzo on STP.” This is particularly noteworthy for a few reasons:

It was in the magazine that Cardoso edited and so he almost certainly had seen it.

It appeared in the middle of June, quite possibly before his letter to Thompson.[3]

It was written about drugs, with the context suggesting “going wild” or “losing control” on a hallucinogenic substance. (Although the article was about LSD, the reference was to taking STP, another psychedelic chemical.)

Regarding #2, do not know when exactly Cardoso wrote to Thompson but even by the end of May Thompson had not received copies of that issue of Scanlan’s. If Cardoso received the magazine in June, he possibly wrote to Thompson in the middle of the month. It is also possible that he had read the Alpert story well before the magazine’s print date. Until the Thompson archives are opened to researchers, questions like these will be impossible to answer definitively, but it seems more than a little coincidental that Cardoso encountered the word “Gonzo” in that context in what was probably the same week that he wrote to Hunter Thompson calling “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” “pure gonzo.”

Sorry, Mr. Giuliano, but your claim to fame has been shot to pieces like a propane tank at Owl Farm.

Conclusion

Given all the information above, there are a number of conclusions that people could draw and I don’t mean to suggest that anything I write in this concluding section should be taken as the absolute truth. I have pulled together more sources than had previously been found but they honestly just complicate the story even more. As such, I will have to speculate a little and I invite you to do the same.

Despite my prior doubts, I now feel that Brinkley’s explanation has a degree of plausibility. The fact that Thompson and Cardoso liked to screw with people and invent false histories means that it is hard to take their versions seriously and as we have seen they both contradicted themselves and each other quite thoroughly. As for Giuliano’s, he certainly has proof of writing “gonzo” as an adjective just weeks after Thompson’s Kentucky Derby article, which is an interesting consideration, but it does not prove that Cardoso stole the word from him. It is far likelier that Cardoso saw the word in the June 14 article about Richard Alpert and borrowed it. (In fact, the only other explanation could be that he inserted it into the article after using it in his letter to Thompson.)

However, do these explanations need to be mutually exclusive? Does one theory necessarily discredit another? I don’t think so. Personally, having looked over all the evidence, I think that Thompson probably heard the song in 1960 through his friend Paul Semonin and was pleasantly surprised when, about a decade later, Cardoso re-introduced it in a new context. I believe that Cardoso’s letter to Thompson saying that “The Kentucky Derby was Decadent and Depraved” was “pure Gonzo” was inspired by the June 14 article in the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine. Thompson had written a story about being extremely intoxicated and this article used “Gonzo” in that same sense.

This was around the time Thompson was developing “Freak Power” and embracing the moniker “freak,” so perhaps he gleefully adopted this word of obscure origin. He was not just a freak… He was his own kind of freak, a Gonzo journalist. On the one hand, it brought to mind a frantic, oddball song he quite liked and on the other it seemed like regional slang for “off the wall” and related to being completely twisted on hallucinogens. Repurposed, it described his unique style of writing, which was neither fiction nor journalism, but something created entirely to deal with the violent and corrupt world around him and to counteract the inadequacies of traditional media.

We will probably never know for certain the exact etymology of “gonzo” because it possibly has multiple origins. As Thompson said in a 1974 Playboy interview, “Gonzo is just a word I picked up because I liked the sound of it.” What is important is that it came to describe the style of writing of one of the twentieth century’s most brilliant and bizarre minds.

A Final Thought

I said at the beginning that I did not want to mark this anniversary with an essay on the rank incompetence and criminal stupidity of those tasked with managing his literary estate, but I feel that I must say a little something, in part because of the frustration felt as I tried to research this subject. Essays like this are few and far between not only because Thompson’s fans are mostly illiterate and the educated folks that admire him consider him a guilty pleasure. It is not only that the academy sneers at him, either, and makes it hard to publish serious inquiries into his work. Worse than all that is the fact that in the twenty years since his death the Thompson estate has done almost nothing to honour or advance his legacy. We are given Gonzo-brand gin, Gonzo jewellery, Airbnb listings for his cabin, and other commercial endeavours that would be easier to stomach were there any effort at publishing something new. Instead, we get the occasional new cover for an old book or introductions written by literary luminaries such as… the drummer from Metallica and the host of Jackass. Seriously. Where is the third collection of his letters? What about a well-edited collection of early writings? What about his short fiction? It’s obvious to anyone that his work was uneven and in later years simply appalling, but there was so much that was golden, particularly in the first few decades. Look at the estates of writers such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs. You can pick faults with the Kerouac estate if you want, but at least these people have made genuine efforts to keep him relevant. It was only through the effort of one private collector that any unpublished Thompson documents have been made public because those who actually have access and the means to share have done quite literally nothing. They have no interest in helping researchers or doing anything for Thompson’s legacy. They only want to earn easy money. A great writer’s legacy is in tatters and he looks set to be forgotten because these people do not give a fuck. His image will be in the domain of the costume-wearing fuckwits on Facebook who think that it’s edgy to post pictures of their joints and who probably don’t realise that Johnny Depp and Hunter Thompson were different people. This essay was the result of much research, yet anyone can see that it was limited by the fact that it is impossible to access Thompson’s archives. No scholars are allowed to see his unpublished letters, early drafts of manuscripts, and other important documents. It is all hidden because of stupidity, greed, and apathy. The failure of the people tasked with running the estate is borderline criminal. Shame on them all.

And one more (stupid) connection…

As a weird sidenote… If you attempt to use Google to research this topic, you will no doubt encounter another famous Gonzo and, weirdly enough, he also came into existence in 1970. The Muppet Show introduced the character of Snarl for its Christmas special and this recurring character evolved over the next six years to become Gonzo in 1976.[xxi] We can obviously discount the possibility of Thompson or Cardoso borrowing the word from the Muppets but one wonders whether or not Jim Henson borrowed it from them. By 1976, however, Thompson was more annoyed by Garry Trudeau’s creation Uncle Duke, which used Thompson’s likeness without permission.

[1] Thompson was an incorrigible mythologiser and frequently made up stories about himself to highlight his outlaw nature and cement his literary legacy but these do not hold up to much scrutiny. Many of them are so comical that he probably never thought they’d be taken seriously but others appear in his various biographies as fact because he repeated them with such conviction that they were taken to be true. Also, Thompson was careful to fabricate stories that were hard to disprove. Thus, I have my suspicions about his version of writing the Kentucky Derby story and having it labelled as Gonzo Journalism. For one thing, he began by saying that he’d spent 3 days locked in a hotel room. Soon, it was 4 days, and then after that it was 6 days… The specific details also change from one version to the next. A close reading of his letters suggests that he wrote out his story but simply could not expand and polish it to the extent that he wanted, and later he seems to have added the idea of his notes being completely unedited, which is obviously untrue. In any case, it is still important that what he sent off was a version of his notes that conveyed immediacy even if he exaggerated the extent to which these were unedited.

[2] We can see this in a 1974 response to a journalist. On the origins of Gonzo, Thompson says “I got a letter from a guy in Boston after a Kentucky Derby story, saying that’s pure Gonzo I thought that was pretty good. It was better than ‘New Journalism.’” [The Post-Crescent, April 11, 1974] Thompson seems here to highlight his originality. He has made similar comments elsewhere.

[3] Again, we do not know when exactly Cardoso wrote to Thompson but even by the end of May Thompson had not received copies of that issue of Scanlan’s. If Cardoso received the magazine in June, he possibly wrote to Thompson in the middle of the month. It is also possible that he had read the Alpert story well before the print date. Until the Thompson archives are opened to researchers, questions like these will be impossible to answer definitively.

[i] Fear and Loathing in America, p.295

[ii] Fear and Loathing in America, p.375

[iii] Great Shark Hunt, p.106

[iv] Ancient Gonzo Wisdom, p.71

[v] Boston Globe, May 21, 1930, p.14

[vi] Hunter: The Strange and Savage Life, p.124

[vii] https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/17/books/review/gonzo-nights.html

[viii] Lincoln Journal Star, June 4, 1975

[ix] High Times Sept. 1977

[x] The Vancouver Sun, Nov 4, 1977

[xi] When the Going Gets Weird, p.168

[xii] https://www.williammckeen.com/an-essay-6/

[xiii] https://www.wordorigins.org/big-list-entries/gonzo

[xiv] Detroit Free Press, March 24, 1974

[xv] Outlaw Journalist, p.150

[xvi] E-mail, March 2024

[xvii] https://berkshirefinearts.com/03-07-2013_british-rocker-alvin-lee-dead-at-68.htm

[xviii] https://berkshirefinearts.com/06-04-2014_dr-gonzo-william-j-cardoso.htm

[xix] https://berkshirefinearts.com/03-07-2013_british-rocker-alvin-lee-dead-at-68.htm

[xx] https://berkshirefinearts.com/03-07-2013_british-rocker-alvin-lee-dead-at-68.htm

I was talking to a friend about this a little while ago. It is a shame that I think Hunter isn't getting his due as an important writer and only seems to exist as a fictional character, the Duke persona, if at all to younger generations. When his work merits attention, perhaps more so now in many ways. Because I am such a fan I love that Kerouac's estate is still putting "new" stuff out. For me every new publication, even if not as great as his best work, is interesting and worth a read. And I don't think on a larger literary scale Kerouac gets his proper respect either from academics etc. But at least there is an effort to keep the flame burning. I don't know the working of Hunter's Estate aside from bits and pieces I've read. Is Brinkley still involved? Is there tension between Juan and Anita that inhibits things? And I agree, these reissues with people like Lars Ulrich and whoever the hell did the Fear and Loating in Las Vegas 50th intro, does no favors. I'd love to see a collection of early works, short pieces like Fire in the Nuts, the third book of letters, hell I'll take unfinished pieces like whatever state Polo is My Life is in or the NRA book Brinkle mentions in one of the documentaries. I'd love to read these fragments, anything I think would help shine a light on Hunter for new generations. I have multiple copies of his book and fully plan to give my kids copies and hope that helps keep Hunter's flame burning in some small way

I really enjoy your indepth excavations of hidden corners of the Beat universe. I'm sure there's many other Beat / Counterculture nerds out there who feel the same. I hadn't heard about the dishevelled state of the HST Estate. It's disheartening, and reminds me of the incredibly hamfisted 'editorial' work done on Jim Morrison's two posthumous poetry / notebook collections (Wilderness and The American Night), and the nightmare of Ken Kesey's archive rotting away in a barn.